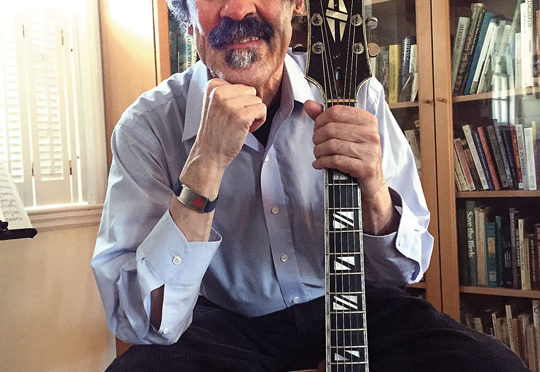

Peter Cho of Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA) is a pianist, educator, and union board member whose work runs the gamut, from advocacy for all musicians to mentoring a younger generation of music students.

At the Louis Armstrong Jazz Camp, where Peter Cho of Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA) has taught for the last 20 years, he says, “We make sure music students are well-rounded. Part of that is making sure they understand their capacity for other things. If you’ve got an analytical mind, explore music composition or the music business, maybe as a booking agent or a talent buyer. It’s a holistic approach to education.” An educator and jazz pianist, Cho is the executive dean of Delgado Community College’s West Bank Campus.

For a much sought-after pianist, Cho admits he had a rather inauspicious start, learning piano as a kid—and hating it, he claims—because it required too much discipline. In high school in Auburn, Alabama, he played the clarinet in the jazz band and participated in music festivals around country.

Before he knew it, the kid who was heading to Auburn University for pre-med was getting scholarship offers for music. Cho says he owes his sudden change of heart to his father, a professor of veterinary medicine, who said, “I don’t want you to be an old man, wondering, ‘what if?’” Cho ended up at Loyola University on a scholarship as a jazz studies major.

In New Orleans, he began playing gigs immediately. Cho would take the streetcar downtown to the Maison Bourbon, where he’d met an old piano player by the name of Ed Frank. Cho says “I’d hang out with him every day. He was my unofficial teacher and mentor.” By the time he was 19, Cho was playing piano professionally.

The cultural economy is the life force of New Orleans rooted in older musicians passing the mantle on to younger musicians. Like elder statesmen of the Marsalis and Batiste families, Cho sees his job as an extension of this, training younger generations of musicians. He says, “As a community we are doing what we need to do to make sure that engine of creativity continues.”

As a dean and a musician Cho has found what’s meaningful. “You understand how you fit into your community, how what you do matters to others,” he says. The college enlists musicians from the community, many of whom are retired, to teach classes and provide students with real-world ensemble experience. “They want to give back. Professional musicians are mentoring. It’s the internal program linking students to the actual music scene.”

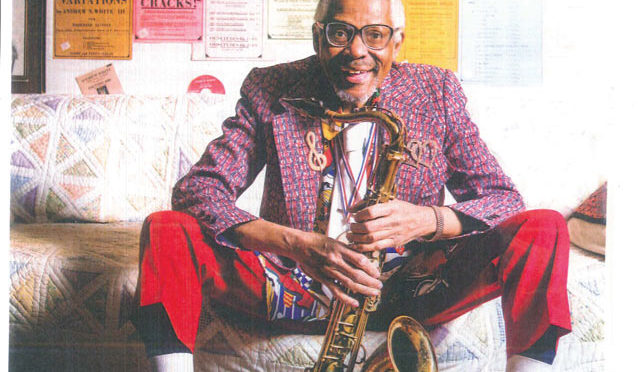

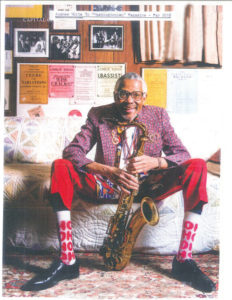

Early on, Cho (who went on to earn a Ph.D. in Education Administration from the University of New Orleans), studied with Michael Pellara. He’s responsible for many of the city’s best musicians, including the younger Jon Batiste of Local 802 (New York City), who also came out of the Armstrong camp and is now the musical director of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Pianist Barry Doyle Harris of Local 802 served as an inspiration for Cho. Nearly every night, since 1990, the 48-year-old Cho has performed with James Rivers and his band, The James Rivers Movement, which has been a fixture in the city for nearly 50 years. He is also a pianist for the Victory Swing Orchestra of the WWII Museum.

On stage, he’s performed with Willie Singleton of Local 56 (Grand Rapids, MI), Jimmy Heath of Local 802, and Johnny Vidacovich, George Porter, and Delfeayo Marsalis, all of Local 174-496, to name only a few.

An executive board member of Local 174-496 since 2006, post Katrina, Cho knows firsthand the permanent shadow the storm cast over the city, where once-robust music neighborhoods have been forever altered. When Katrina struck, the natural musical traditions of individual areas were uprooted. “A lot of musical families were displaced. Musicians came back, but they weren’t able to settle in old neighborhoods. The actual engine that created this musical tradition and culture has been disrupted,” Cho explains.

Musician friends of Cho’s, who were forced to relocate, say one positive effect of displacement is that there now exists a fairly thriving New Orleans style jazz music scene in other cities, like Houston and Atlanta. He says, “These cities are seeing an influx or growing New Orleans musical and cultural heritage.”

The loss of neighborhoods and the corner clubs after Katrina created unexpected opportunities for musicians. But Cho says, “There are districts where a lot of musicians are willing to play for the door or tips, and aren’t necessarily compensated as professionals. The local has been trying to fight for musician’s rights, trying to organize and give all musicians a roadmap.” He’s encouraged, noting, “I’m seeing a lot of attitudes of nonunion musicians change; if we’re willing to undercut each other, everybody loses.”

“Right to work” laws obviously obstruct the aims of the local union, but with the present board and Deacon John Moore at the helm, Cho sees more solidarity among all musicians, union and nonunion alike. Moore’s efforts, in fact, have greatly improved working conditions for musicians.

“Once nonmembers understand the advocacy and how we as musicians fit into the cultural economy and how we, as raw materials of this economy, have more power. If musicians boycotted playing any type of music for one day, the ramifications would be tremendous,” he says.

“That’s how you mobilize and show what type of clout you have. It gives you more leverage and you’re better able to go to club owners and say, ‘Hey, we’re not going to take these conditions anymore.’” In addition to highlighting the benefits of a pension, the local advocates financial literacy. Cho says, “One of the things we tell musicians is: pay yourself first, you’re worth it. And you’ll have something to fall back on.”