While our union officials have been monitoring the COVID-19 outbreak and potential impacts on musicians since it first became a global health emergency in late January, once music events began being canceled and restrictions on large gatherings were announced by both US and Canadian officials in early March, that is when the impact on musicians and their livelihoods became stark.

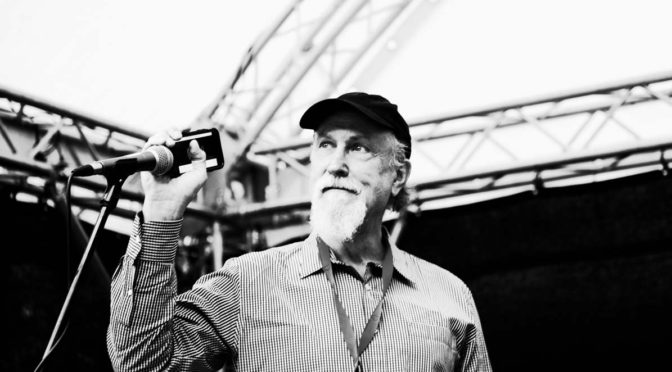

On March 3-4, President Hair was in Washington visiting legislators on union-related legislation. Although the coronavirus was still in its infancy as far as its North American presence, Hair says the people in the nation’s capital were beginning to panic, and it immediately got him thinking about the AFM’s response.

On March 5 and 9, respectively, the AFM’s two largest locals—Local 47 (Los Angeles) and Local 802 (New York City), which cover Hollywood and Broadway musicians—began posting updates and information on their websites to offer their members guidance on health and emergency relief resources. The Local 802 Executive Board began working in conjunction with the 802 Emergency Relief Fund and Musicians Assistance Program to get musicians help as quickly as possible, while the Local 47 Executive Board established an Emergency Relief Fund for members who have lost revenue due to work stoppages, as has the Music Fund of Los Angeles.

Also on March 9, all employees at the AFM headquarters in Times Square who could do their work remotely were allowed to work from home, and any essential employees who needed to work at the office were given limited schedules to avoid being in rush-hour crowds. The office was also supplied with hand sanitizer, cleaning wipes, and gloves to help prevent contagion. (The New York office closed, with all employees working from home, starting March 19, as did the West Coast Office on March 20.)

On March 12, the day Broadway theaters closed their doors, President Hair issued a statement in response to limits being placed on public gatherings: “Union musicians in the United States and Canada are committed to doing everything possible to limit the spread of COVID-19, but this will have a disastrous impact on musicians and so many others who live gig to gig. It is critical that both national and local governments take immediate action to provide economic relief including expanding unemployment benefits and an immediate moratorium on evictions, foreclosures, and utility shut-offs.”

Actors’ Equity Executive Director Mary McColl also released a statement, in which she said the decision to limit public gatherings, “means tremendous uncertainty for thousands who work in the arts, including the prospect of lost income, health insurance, and retirement savings.” International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE) International President Matthew D. Loeb also called on the federal government to take decisive action and issue a relief package to entertainment industry workers. “Entertainment workers shouldn’t be collateral damage in the fight against the COVID-19 virus,” he stated. “Film and television production alone injects $49 billion into local businesses per year, and the overall entertainment industry supports 1.2 million jobs in municipal and state economies.”

Helping Traveling Musicians

The cancellation of Broadway shows includes all the travelling shows, and many union members were left out on the road with employers offering only partial payment for their final week of work, says AFM Touring/Theatre/Booking Division Director Tino Gagliardi. Gagliardi has been in constant contact with all the AFM touring musicians to keep them informed of the situation.

He also has been meeting with other entertainment industry union officials and the Broadway League to sort out the issue of worker benefits and compensation. “Some companies have given notice to musicians they will only be paid a partial week for their last week. The union’s position is full payment of course,” he says. “The League’s got to do the right thing here. What we’re looking for is full compensation through the rest of the week that was canceled plus additional financial relief for the musicians through additional wages based on the type of production and health care benefit contributions until April 12, with a commitment to resume discussions on the possibility of additional health contributions the week of April 6.”

An agreement was reached on March 21.

Side Letter to Integrated Media Agreement

On March 13, the day President Trump officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a national emergency, the AFM announced it had signed an agreement with the Employers’ Electronic Media Association (EMA) to enable livestreaming of concert performances by a signatory employer that has been adversely affected by the spread of COVID-19. This side letter to the 2019-2022 Integrated Media Agreement guarantees no disruption in compensation or benefits for any musician for a 30-day period following the date of posting of the first streaming content.

“What the side letter does is to allow the employer to maintain an online presence when maintaining an in-person presence (for either audience or musicians) is either impossible or imprudent in the limited context of the COVID-19 pandemic,” explains SSD Director Rochelle Skolnick. “An employer must elect to use the side letter and the musicians of the orchestra must vote to approve its use. It is not automatically applied to any orchestra.” She says the use of the side letter also does not interfere with the ability of a local, orchestra committee, or musicians to make their own decisions about gathering together to rehearse or perform. “In short: agreeing to use the side letter does not create any new obligation for you to show up to work,” she explains.

Online Resources

This COVID-19 side letter was the first document to be placed in a newly created folder in the SSD section of the AFM.org website called “Corona Virus Resources.” The folder also contains legal guidance on force majeure (“Act of God”) aspects of collective bargaining agreements and a Q&A document regarding musician attendance and COVID-19 concerns; it will also be continuously updated and augmented as conditions change.

In addition to the new SSD digital resource, there is now a COVID-19 resource page with information and helpful links at www.afm.org/covid-19/.

Lester Petrillo Fund

Union officials also have announced reminders that any members who contract COVID-19 and lose work because of it can apply for limited emergency financial aid through the Lester Petrillo Memorial Fund. The Fund was established to assist members in good standing who become ill or disabled and are unable to accept work. A member would qualify for assistance if he/she is diagnosed with coronavirus and/or he/she tests positive for coronavirus and is quarantined.

Members and local officers may download Petrillo Fund applications from the AFM website. Go to www.afm.org and type “Petrillo Memorial Fund” into the search bar. Completed applications together with supportive medical documentation should be submitted by members to their local unions, which will then submit them to the Federation.

Across the northern border—which the Canadian government closed to foreign travelers on March 16—the Canadian office of the AFM, located in Toronto, started putting emergency office measures into place on March 13. These measures included allowing staff to work from home if possible, having reduced office hours to avoid peak travel times in transit, having a maximum of three staff members in the office at one time, offering hand sanitizer around the office, and practicing increased cleaning of common surfaces in the office, says Alan Willaert, Vice President from Canada. The Canadian office closed until further notice on March 24 after the Premier of Ontario and the Mayor of Toronto both declared a state of emergency and ordered all non-essential businesses to close for two weeks.

The Canadian Office of the AFM, in coordination with the Canadian Actors’ Equity Association and the Toronto Musicians’ Association, also started the Save Live Arts in Canada initiative (www.savelivearts.ca) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The initiative encourages all who work in the live arts to sign a petition addressed to all elected officials in Canada, which urges certain health and financial actions be taken to help members of the entertainment sector in the face of unemployment.

Urging Federal Response

Also on March 13, Willaert sent an open letter to the Government of Canada, urging support for musicians due to an unprecedented loss of work caused by reaction to the Coronavirus. “The CFM is requesting that government adopt emergency measures in this exceptional situation, to provide security to counteract this critical loss of revenue, through whatever means necessary,” Willaert wrote. “These steps may include a waiver of the one-week waiting period for Employment Insurance (EI) benefits (in the case where the musicians are entitled), to expanding the benefit to include freelance workers who provide their services as self-employed contractors, to ensuring that compensation is made available for musicians who have had gigs or tours canceled for both lost revenue and other expenses, such as the hundreds of dollars, or thousands paid to USCIS as petition fees for P2 visas for US entry. Consideration must be made as well for proper funding to help musicians and symphony/theatre organizations recover, as well as assistance to stimulate and revitalize the industry once the virus has been contained and/or eradicated.”

Willaert also signed on to a letter from the seven Canadian entertainment unions to the Canadian minister of heritage and multiculturalism urging him to extend income support to workers not eligible for EI sickness benefits. Many workers in the Canadian entertainment industry are not classified as employees under Canadian laws, and therefore are not eligible for EI benefits for any loss of work due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“We are concerned the government may forget the importance of our industry and the need to also protect the workers who rely on it for their income,” the letter states. “We are already seeing cancellations of screen-based productions and live performances with more anticipated. Workers who are signed to productions rely on those contracts, which can range from several days to several months. The loss of that expected income will be devastating to these precarious workers. Production insurance is not covering cancelltions related to COVID-19.”

On March 14, President Hair issued a statement on the pandemic’s impact on musicians and other gig economy workers:

“As events related to the fast-moving coronavirus pandemic evolve, emergency declarations in many locations have banned all but small-sized public gatherings in an effort to protect families, save lives, and prevent the spread of the disease. These actions have led to the shuttering of large, medium, and small venues, sporting facilities, and the preemption of live media production involving studio audiences. This has prompted the widespread cancellation of concerts, shows, theatrical productions, festivals, and musical performances of every kind—all of which have inflicted disastrous economic effects upon performers who often live gig to gig and who bring joy to the world wherever groups are gathered.

“Tens of thousands of musicians and others have suddenly found themselves without income, without the means to feed and protect their families, and who may lose healthcare coverage during these shutdowns. Today, a state of national emergency has been declared which frees up $50 billion in federal funds for use in response to the accelerating surge of infections. When considering funding assistance and relief for working people, Congress and state and local lawmakers should pay particular attention to those who work and perform in the entertainment industry, whose gigs have gone dark, and who are bearing the financial brunt of these shutdowns the most.”

Like their Canadian counterparts, the major US entertainment industry union leaders are also coordinating to protect their members from the effects of the coronavirus and the governmental response to it. These leaders—part of the coalition comprising the AFL-CIO Department for Professional Employees—had a teleconference on March 16 during which they discussed all aspects of the situation, particularly how to ensure that our elected officials in Washington DC stand up for creative professionals.

They drafted a letter to government officials in which they advocated for emergency economic support for entertainment industry professionals. Specifically, they urged legislators to create a special Emergency Coronavirus Economic Support Benefit geared toward entertainment workers who have a bona fide, good faith work offer that gets canceled due to the coronavirus, as well as the creation of a benefit similar to the Emergency Paid Leave benefit included in the first Coronavirus Response Act legislation (signed into law on March 18) but available to those who cannot work due to production shutdown rather than due to illness, quarantine, or family caregiving needs.

“We are working closely with the Arts, Entertainment, and Media Industry (AEMI) unions through the AFL-CIO’s Department for Professional Employees (DPE) to speak with one voice urging Congress to include musicians and other arts and entertainment workers in any subsequent bill to help our members,” says AFM International Secretary-Treasurer Jay Blumenthal.

While President Hair and the rest of the AFM leadership and staff are working around the clock with other national entertainment unions to protect their members, they are encouraging members to stand up and speak out as well. “Musicians need to directly contact their congressperson and senators to urge them to protect entertainment workers during this unprecedented crisis,” President Hair says.

All AFM members are encouraged to visit www.afm.org/covid-19, scroll to the bottom, and fill out the “Emergency Action – Contact Congress” form to let Congress know that they need to protect entertainment workers, thousands of whom are unable to pay for rent or food and are finding their healthcare coverage in jeopardy.