Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Featuring works by three composers who have a special relationship with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Gandolfi, Prior & Oliverio: Orchestral Works is a celebration of the orchestra’s 75th anniversary and the two-decade tenure of its fourth music director, Robert Spano.

The album captures the collaborative nature of Spano and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, who established the Atlanta School to champion the next generation of American composers.

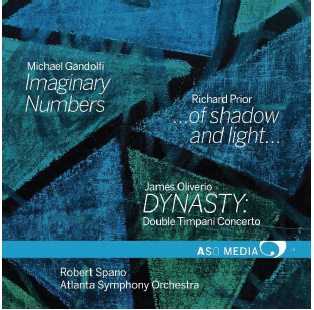

The recording is comprised of studio recordings of Michael Gandolfi’s quadruple concerto Imaginary Numbers, Richard Prior’s lyrical tone poem …of shadow and light… and James Oliverio’s DYNASTY: Double Timpani Concerto, which was commissioned by and written for ASO principal timpanist Mark Yancich, of Local 148-462 (Atlanta, GA) and his brother Paul Yancich, of Local 4 (Cleveland, OH), principal timpanist of the Cleveland Orchestra.