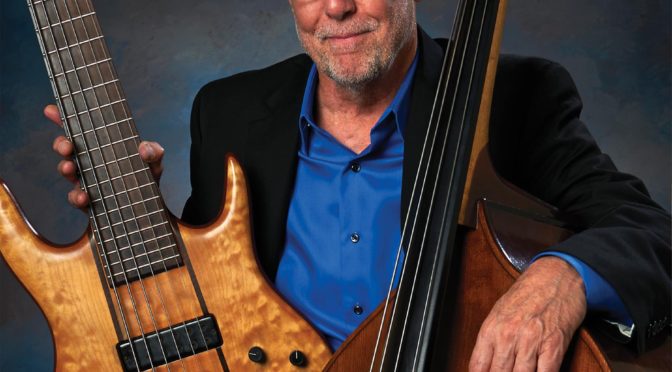

At the Denton Arts and Jazz Festival in Denton, Texas, Mayor Chris Watts read a proclamation designating April 29, 2016 as Jay Saunders Day in Denton. In a short speech Watts highlighted the Local 72-147 (Dallas-Ft. Worth, TX) member’s career contributions to the University of North Texas (UNT) Jazz Studies Program. Denton Arts & Jazz Festival Director Carol Short also recognized Saunders and his wife Pat for more than 32 years of volunteer service to the festival.

At the Denton Arts and Jazz Festival in Denton, Texas, Mayor Chris Watts read a proclamation designating April 29, 2016 as Jay Saunders Day in Denton. In a short speech Watts highlighted the Local 72-147 (Dallas-Ft. Worth, TX) member’s career contributions to the University of North Texas (UNT) Jazz Studies Program. Denton Arts & Jazz Festival Director Carol Short also recognized Saunders and his wife Pat for more than 32 years of volunteer service to the festival.

Saunders earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree at UNT, where he was lead trumpet for the school’s premier jazz ensemble, the One O’Clock Lab Band, during the 1960s. In his distinguished career, Saunders has played with the Stan Kenton Orchestra, US Army Studio Band, Dallas Summer Musicals, Casa Mañana Musical Theater, Dallas and Fort Worth symphony pop series, Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, Ray Charles, The Supremes, Henry Mancini, and countless others. He’s recorded 11 albums with the Stan Kenton Orchestra and one with Doc Severinsen. Plus he’s recorded music for documentary films and countless commercials on every major television station.

Saunders has served with distinction on the faculty of the UNT School of Jazz Studies for 16 years as a full-time lecturer and for seven years as an adjunct faculty member. He has directed the school’s Three O’Clock Lab Band for many years, has directed the Two O’Clock Lab Band for the past six years. He’s directed the One O’Clock Lab Band for two years, during which it received a Grammy nomination.