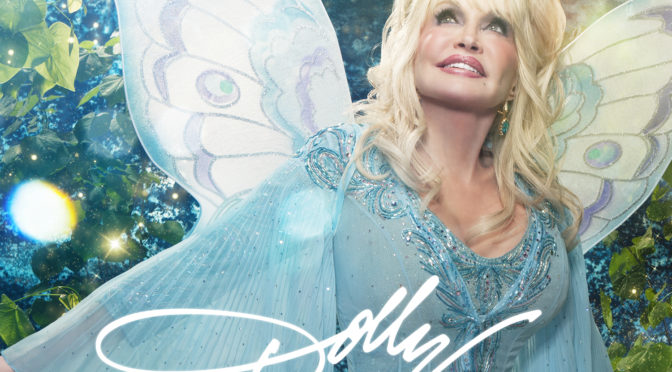

Christina Linhardt of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) works with a nonprofit arts therapy organization, Imagination Workshop (photo credit: Anthony Verebes)

Christina Linhardt of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) is a musical chameleon. Her talent spans classical music, high opera, folk dance, cabaret, and when called for, the occasional circus performance. Her artistic upbringing meant traveling the world, spending summers in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, among artists and musicians, notably the Arnold Schoenberg family.

In Berlin, she attended the Goethe Institute, later studying French at the Eurocentre in Paris, and acting at Oxford University. Back in the States, Linhardt graduated in music and vocal arts from the University of Southern California.

A recurring role for Linhardt is that of chanteuse. Her “Classics to Cabaret” act is a favorite both here and abroad. In Germany, it headlined the opening of the Grand Concert Hall Parksalle in Dippoldiswalde and the reopening of the Palace Ligner in Dresden. Linhardt adds, “I have done it in Germany with the Berliner accent and included songs made popular by Marlene Dietrich.”

Linhardt has a gift for innovative art forms. She had exposure to diverse traditions early on—for instance, attending cabarets in Vienna—and says, “I was influenced by the authors, writers, and artists I lived amongst as a child in Europe.” Her dramatic interpretation of new and avant-garde music is often accompanied by professional acrobats and clowns. She has successfully parlayed opera, theater, and contemporary rhythms into her CDs Circus Sanctuary and Voodoo Princess, which were both recorded under union contracts.

With fellow Local 47 members Susan Craig Winsberg and Carolyn Sykes she established the Celtic Consort of Hollywood and with Carol Tatum of Local 47 and Cathy Biagini she performs with Angels of Venice—“a classical trio with a new age twist,” says Linhardt, who is also a featured soprano on their CDs. In addition to vocals, she plays flute. “We do a lot of Medieval and Renaissance music: harp, voice, mandolin, cello. It has variety.” With longtime accompanist and pianist Bryan Pezzone of Local 47, this summer Linhardt is planning local concerts and another recording, also in a Celtic-Renaissance vein.

Linhardt points out that she’s relied on the benefits of the union throughout her career. “Early on, I was a music contractor for a score contracted through Local 47. They gave me legal advice when I was producing albums and doing radio promotion—what to do and how to not get scammed.”

As a soloist, Linhardt has performed classical arias and premiered new opera pieces—many written exclusively for her—in Los Angeles and throughout Germany. She is the official national anthem singer for the German Consulate and represents Berlin every year at the Los Angeles Sister Cities Festival.

Her clown and mime training landed her a part in the Vamphear Circus in 2006, when the troupe traveled to the naval base on Guantanamo Bay. “A friend of mine said he was going to Guantanamo Bay for a gig,” She remembers saying, “You’ve got to get me on that circus gig.’”

Known primarily for the notorious detention camp, the sequestered region is also home to US military personnel and service workers. Linhardt says, “At the time, there were about 2,000 children on Guantanamo Bay. It was very 1950s. People said it was a great place to raise your kids. It was a Twilight Zone set—almost surreal.”

The subsequent documentary Guantanamo Circus, by Linhardt and fellow performer Michael Rose, won the Hollywood FAME Award for Best Documentary.

Off stage, Linhardt works for the Imagination Workshop (IW), a nonprofit theater arts organization that uses music and art as therapy for senior citizens, those with Alzheimer’s disease, at-risk youth, and homeless veterans, among others.

Linhardt says, “Music is an effective tool, especially, with Alzheimer’s patients, who cannot engage in the same way,” she says. “I’ll have people who can’t speak, except through the words of the music. After a session, sometimes we can get a few words out of them because they just sang the song. Music activates different parts of the brain and that’s why music can still be remembered when all other memory is gone.”

For the past 16 years, she has been working with veterans with PTSD. “As the veterans are highly functional, we take the program to the next level, like a play written by and starring the participants. A lot of vets say, ‘For once, we don’t have to be our addiction; we don’t have to be our PTSD; we don’t have to be our past. We can try to be somebody else.’ It’s a new opportunity,” Linhardt says.

Recently, she has taken on yet another role, that of staff writer for the California Philharmonic, where she writes a Meet the Musician series. “Classical musicians are trained to be soloists, to be super stars,” Linhardt says, “I wanted to give each musician a moment in the limelight.”