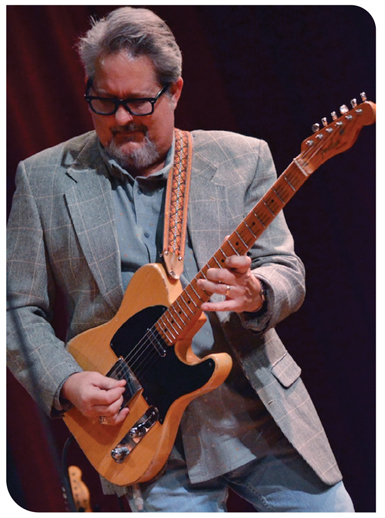

Musical rebellion isn’t just for rock-and-rollers, though country and blues multi-instrumentalist James Pennebaker did spend a bit of time playing around with rock as a kid when he supplemented his classical violin studies with British Invasion records. But as a Fort Worth native, the siren song that pulled him away from his orchestral future had a bit more of a twang.

“I got really into Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys in high school. All the Western swing bands, really, but Bob Wills was from Fort Worth and I always had that connection,” says Pennebaker, currently a member of Local 257 (Nashville, TN). “I kept on playing swing and country and blues, but I went to college as a violin major until I left in 1976 to run off with the circus. I was 19. My orchestra-mates thought I was nuts.”

“The circus” was the touring band of roots music trailblazer Delbert McClinton, also of Local 257, with whom Pennebaker has toured on and off for his entire career, along with stints in the touring or recording bands for other 257 members Lee Roy Parnell, Pam Tillis, and many more.

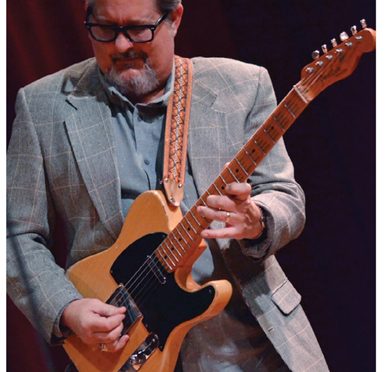

Playing guitar (acoustic, electric, and steel), mandolin, and fiddle in McClinton’s touring band is Pennebaker’s primary gig even still, but times have never been more uncertain for a touring musician. And as he observes the COVID-19-brutalized live music landscape, he’s as relieved as ever to be a member of Local 257.

Tennessee has had sweeping right-to-work/anti-union laws since the 1940s, but that hasn’t stopped the country music capital’s local from being one of the most powerful in the country. “When I first moved to Nashville 20, 30 years ago, you had to be a card-carrying member if you wanted to get hired for anything—recording, tours, you name it,” explains Pennebaker.

He already had his card, having joined up with the Fort Worth local (now Dallas-Ft. Worth Local 72-147) in 1979 when McClinton had some commercial success with the album Giving it Up For Your Love and performed a slate of national TV appearances. Union membership paid off quickly, though, as Pennebaker continued to play fiddle, mandolin, and guitar around Fort Worth when he wasn’t on the road. “If you got stiffed, someone from the union would go out and make sure you got paid,” he says—no small deal for a young picker raising a family on gig money.

Other union benefits have been useful over the years. “They’ve helped me with health insurance, with musical instrument insurance, and then there’s the pension, which … well, I might be taking that sooner than I thought, given the situation.” The pandemic-related lockdown has Pennebaker spinning his wheels. “I’m a touring musician. I don’t really do session work anymore. All I want to do is get back on that bus with Delbert and play shows,” he says.

A loss of touring income this summer comes as a particular sting, as Delbert McClinton and his Self-Made Men are coming off a fresh Grammy Award win, having won the trophy for Best Traditional Blues Album for Tall, Dark, and Handsome at the 2020 ceremonies. “It’s my first trophy, but I still don’t have it. I wouldn’t mind getting to look at it in my living room right about now,” laughs Pennebaker. The Recording Academy’s office is, like just about every office everywhere, currently shut down, and he reports that the Academy employees working from home send occasional messages to remind this year’s winners that they haven’t been forgotten and that their trophies will be in the mail soon.

Pennebaker also self-released a solo album, Under the Influence, in January of this year, recorded in his home studio with a who’s who of Nashville’s finest. “It wasn’t intended to be a big release or anything, it’s just nice to have something to sell at shows. But now CD Baby is shut down and they’re not sending out CDs, so there’s another thing.”

He sees a glimpse of hope in the future, though. “I had a socially-distanced meeting with a friend the other day, an industry lawyer who knows more than just about anyone about this stuff, and he is thinking we might be able to do some performing again by August, at least outdoor things, so that would be a big relief,” Pennebaker says. For this consummate picker, playing live music is far more than just a job, and his ache to return to the stage is palpable. “To take it all away is pretty tough. It’s like having my whole world wash away.”