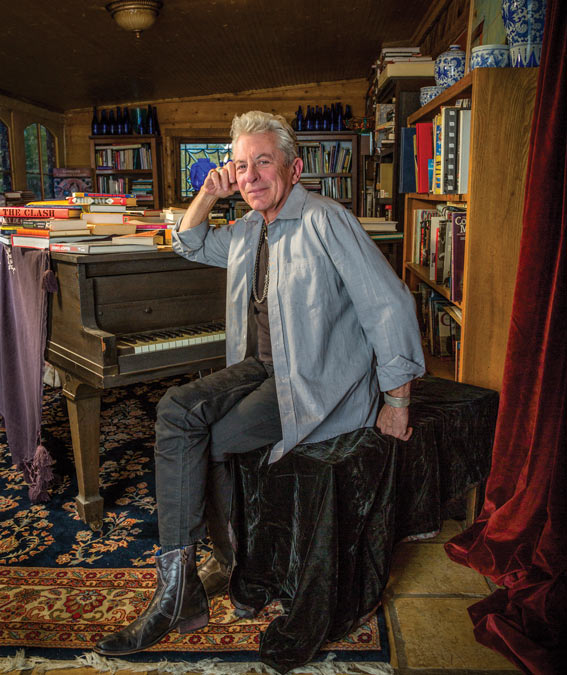

Carl Verheyen of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) is considered one of the most skilled guitarists on the scene—a guitar player’s guitar player—a combination of talent, intellect, and a lot of soul. As a first-call session player turned solo artist, he’s a musical chameleon who consistently demonstrates artistic innovation. “The only thing I turn down is flamenco,” Verheyen says.

With the success of his own band—and doing many concerts abroad—he does fewer sessions these days. Still when he’s home, in LA, he’s happy to do record projects, TV shows, movies, or jingles, recalling a time when he made a living exclusively from union dates. He became a member in 1975, at 21, when he had an opportunity to backup Frankie Avalon provided he had a wah-wah pedal and a union card.

From then on, union gigs provided steady work, about eight to 10 sessions a week, six days a week. He says, “The scales are set for you and the residuals pile up. We used to call it the Special Payments Fund. Now it’s the Film Musicians Secondary Market Fund. In your 20s and 30s, when you’re doing a ton of sessions, you’re not thinking about a pension, but every one of those jingle residuals, every record, every film, adds a few bucks to your pension.”

Verheyen cut his chops playing acoustic guitar in bars five nights a week in his teenage years. “In the beginning, I was just knocked out by The Beatles and The Byrds. Roger McGuinn was a huge influence. That segued into the more virtuoso guitar players like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Duane Allman,” he says.

Verheyen studied at Pasadena City College for two years and for one semester at Berklee College of Music. “I realized the experience I needed was on stage. I understood theory; it came easy. It felt like I could get out there and start playing.” But, he does not recommend that for everybody, admitting, “I was able to fall into some good musical situations, like playing two nights a week with a jazz band—where everybody was better than me. That forced me to learn songs every day and practice seven or eight hours a day and then go back to that gig and be that much better.”

Growing up in a “Sinatra home,” Verheyen says he absorbed the sounds of bossa nova and Carlos Jobim. He was 11 years old when he received his first guitar, a St. George nylon, and one guitar lesson for $2.50. He was hooked. He says his parents had to encourage him to go out and play some basketball. “I’d be out there with my radio in the window. When a song came on that I wanted to learn, I’d stop the game, race upstairs, grab my guitar, and try to figure out the chord changes.”

Getting Started

In his early 20s, he was breaking into TV and film sessions, bolstered by his instincts and flair for improvisation. To sharpen his sight-reading skills, he and another musician helped each other out, informally creating their own one-on-one course. Verheyen traded blues and rock ‘n’ roll lessons for classical guitar lessons. For two hours every day, five days a week, they read music.

In his early 20s, he was breaking into TV and film sessions, bolstered by his instincts and flair for improvisation. To sharpen his sight-reading skills, he and another musician helped each other out, informally creating their own one-on-one course. Verheyen traded blues and rock ‘n’ roll lessons for classical guitar lessons. For two hours every day, five days a week, they read music.

It was a casual jam session with an older guitarist that proved to be a turning point for Verheyen, who says, “This guy showed me 25 different voicings for a Dm7b5 chord, something I never knew existed! That blew my mind.” Laughing, he adds, “I started down what I call the long, dark jazz highway. After five or six years, at 27, I came out of that period. I thought, I like Mike Bloomfield and I want to learn to bend notes like him and I love Albert Lee and I want to learn to play country like him. I like Segovia and I want to play classical guitar like him. Instead of going down one path, why not learn everything you enjoy? It’s just 12 little notes and the only thing that changes is the ornamentation of the style—the phrasing, tone, the choice of notes, and the way you execute them.”

In the jazz years, he played in the same Newport Beach club as a number of big names. Joe Pass happened to be playing one weekend, and Verheyen asked him if he could have a guitar lesson. It was mostly a disaster, Verheyen recalls, because Pass was not an instructor. But it was valuable because Pass said, “If you know a song in one key, you know it in all keys.” That, Verheyen says laughing, was worth the 50 bucks he paid for the lesson.

After much of the 1970s on the jazz scene, he moved to LA in 1980 and played everything from blues and rock to metal. He was a consummate student who transcribed John Coltrane solos, but was equally passionate about learning the groove on Booker T’s song, “Green Onion.”

All Blues

With his newly released album, Carl Verheyen Essential Blues, he decided to rein in one style. “I called my producer about recording two new blues songs. I was planning to make a compilation of all the blues pieces off my 13 albums. He said, ‘I’ve got a better idea. In a month, let’s record a live blues album in three days.’ So, I had a month to put together what I consider the essential blues: Delta blues, Piedmont blues, British blues, Chicago blues, Texas blues, and jazz blues. I tried to come up with what represents the things I enjoy about the blues and my take on it.”

The difference between bluegrass and blues and country rock and fusion? If you ask Verheyen, it’s about attitude and perseverance. He works hard to perfect a phrase. “I practice jazz all the time. Songs like ‘Giant Steps’ and ‘Countdown’ by John Coltrane, ‘Very Early’ by Bill Evans and ‘Falling Grace’—these songs are like puzzles to unlock once or twice a week because they keep your brain sharp; you improvise over difficult chord changes.”

Verheyen owns 70 guitars and 50 guitar amps. “The rule of thumb is, if it sounds good, I don’t sell it,” he says. His collection also includes two banjos, two ukuleles, two mandolins, a mini guitar (tuned to a fifth higher), and two baritone guitars. He alternates vintage guitars, but his preferred all-around is the iconic Fender Stratocaster.

“You need to know how Billy Gibbons gets his sound so you need to own that Les Paul and that Fender Tweed. And you need to understand the different shuffles—the Texans have a different shuffle than Chicago, different from B.B. King. ‘Ornamentation of a style,’ I call it. Eventually, you end up collecting the instruments that give you all those sounds. I’ve kept all that stuff because they’re all colors and textures I put on my own record,” he says.

“Acoustic guitar is another discipline entirely. You have to dig into it. Those are big strings to push around,” says Verheyen. Although he’s a fan of picking up a song and doing a new arrangement to a different tuning, key, or time signature, he says it’s got to be different enough, special, to record.

Verheyen has given lessons to John Fogerty and members of Maroon 5, and is ranked “One of the World’s Top 10 Guitarists” by Guitar magazine and “One of the Top 100 Guitarists of All Time” by Classic Rock magazine. He’s performed alongside Joe Bonamassa, Rick Vito, Stanley Clarke, Robben Ford, and Albert Lee. He can be heard on hundreds of albums—Victor Feldman, the Bee Gees, Dolly Parton of Local 257 (Nashville, TN), and Dave Grusin of Local 47—to name a few. For 32 years, he has been the guitarist for the progressive pop/rock group, Supertramp.

“One thing I’ve learned from being in Supertramp and bandleader Rick Davies [Local 47] is that the set needs to have a certain pacing and it needs to grab people at the first song, get them in the palm of your hand, and then it needs a place to go. Don’t start off with bombastic, crazy stuff,” says Verheyen. For instance, he’ll kick off a set with “The Times They Are a Changin” in a jazzy 6/8 time, a bit like Jimmy Hendrix treated “All Along the Watch Tower.” It’s recognizable and he points out, the 1960s anthem is completely relevant in these uncertain times. He regularly draws on another idol, George Harrison, whose “Tax Man,” played in ska style, is a real crowd pleaser.

The Bandleader

When it comes to playing his own compositions, Verheyen gives his band a lot of latitude. He capitalizes on the talent of his high-caliber musicians by allowing them the freedom to take chances. Although not a jazz group, the music is played with improvisation and interpretation. He says, “To me, it’s better to tell a bass player, ‘Here’s what I’m doing, what do you hear against that?’ unless I’ve written a bass line that’s got to be there because I’m doubling it. The same for the drummer. I always think the drummer is going to come up with a much better part to fit the groove and the song than I can possibly program or write out.”

When it comes to playing his own compositions, Verheyen gives his band a lot of latitude. He capitalizes on the talent of his high-caliber musicians by allowing them the freedom to take chances. Although not a jazz group, the music is played with improvisation and interpretation. He says, “To me, it’s better to tell a bass player, ‘Here’s what I’m doing, what do you hear against that?’ unless I’ve written a bass line that’s got to be there because I’m doubling it. The same for the drummer. I always think the drummer is going to come up with a much better part to fit the groove and the song than I can possibly program or write out.”

The Carl Verheyen Band, recording since 1988, has a 14-record discography. Verheyen has been featured in two documentaries: Grand Designs: The Music of Carl Verheyen and a film about the electric guitar, Turn It Up! A Celebration of the Electric Guitar. His instructional DVDs, Intervallic Rock Guitar and Forward Motion, are legendary. His books include Improvising Without Scales and the handbook, Studio City: Professional Session Recording for Guitarists. He has also contributed to Guitar Player, Vintage Guitar, and Guitar World magazines. He also lectures and gives master classes at the University of Southern California and at the Musicians Institute in Los Angeles.

In addition to performing all over the US, Verheyen has found a market abroad in concert venues and outdoor festivals, noting that, historically, European audiences respond well to improvisation. “Blues and jazz are American art forms that they truly appreciate,” he says. “Sometimes, we’ll try new stuff on the audience and see how they like it. Then, over the months or weeks of being on the road, it begins to evolve into something better. That’s why you always want to play your own music with the people you have a deep musical relationship with and not with pick-up bands.”

For all his success, performing live and working with musicians all over the world, Verheyen says, “There is nothing like a good tracking date. Being in a room with a group of musicians and working up parts that serve the song is really exciting. That moment when the musicians come into the control room and hear the results of the last take on the big speakers is truly one of my favorite times in the studio. You get to hear your tones, from guitars and strings, pickups and pedals, and tubes and amplifiers.”

“But equally satisfying is playing a song you wrote at the kitchen table 20 years ago and seeing the whole front row of a theater singing the words along with you. From studio to the stage, it’s all part of the joy of playing guitar for a living,” he says.