We are more than two months into the coronavirus pandemic and nationwide quarantine, with just a glimmer of hope beginning to shine that society and the economy may start opening back up soon. But even a Phase 1 reopening will not much help musicians, whose profession relies on people in close contact, whether it is in studio, onstage, in a restaurant or bar, or at a large outdoor live music venue. Musicians practice a communal craft, and, currently, musicians are nearly 100% unemployed.

But that does not mean musicians have been forgotten or neglected, that their interests are being ignored. The AFM—at the local, national, and international levels—has been fighting tirelessly for its members’ rights and needs.

It also does not mean that union musicians have no outlet for their creativity. The new reality is a digital one, in which musicians have transitioned to online existence in order to keep creating, marketing, and sharing their music.

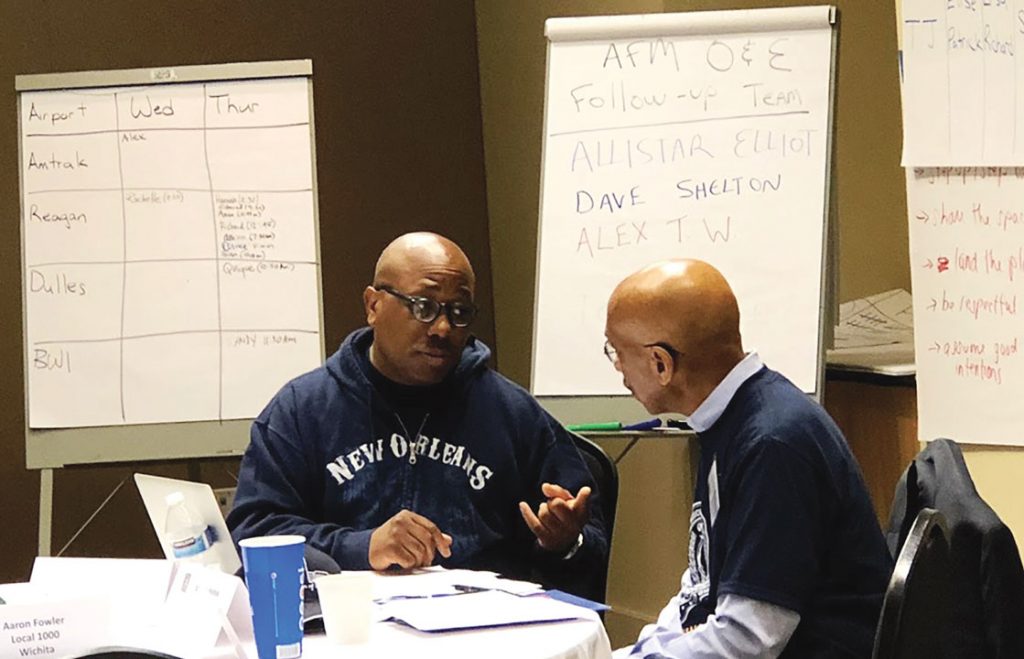

Our Union on the Job

The April issue of International Musician detailed what the AFM had done up to that point to respond to the coronavirus crisis and to assist and protect its members. Since then, union members have relentlessly continued working: lobbying state and federal legislators to include musicians in all relief legislation, ensuring financial and health assistance is available for its members, directing members to further assistance, keeping track of employers and holding them responsible for adhering to union contracts for pay, benefits, and residuals; and creating new, necessary side letters and contracts to expand flexibility in existing contracts, thereby ensuring nobody gets left out of the new reality of the music and entertainment industry.

As President Hair and AFM Legislative Director Alfonso Pollard have explained and will continue to explain every month in these pages, the AFM has been on the front lines in Washington fighting for musicians’ recognition as affected employees in the US economy. After the first national coronavirus relief legislation became law, the AFM, joining with other industry unions and organizations, decried the egregious absence of freelancers, independent contractors, and part-time workers—or W2 wage earners—from the bill, and fought to remedy the situation the subsequent legislation. The AFM is also fighting to ensure that once a return to work is underway, musicians are not forgotten in terms of opening venues, limiting audiences, and ensuring healthy workplaces.

Up north, the Canadian office likewise fought for employment insurance for gig workers, joined a task force to fight for the entertainment industry, and participated in a second coalition of organizations to identify long-term issues of wages, benefits, and safety once musicians return to work. The AFM is present in talks at the highest levels, as shown in Vice President from Canada Alan Willaert’s column last month, in which he was on a conference call with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

On the symphonic side of things, with regular season concerts completely suspended and cancelations for summer seasons beginning to roll in, symphony orchestras in the US and Canada have turned to digital means to maintain connection with their donors, patrons, subscribers, and local communities. The most creative and effective of these strategies capitalize on each orchestra’s unique place in its community and help reinforce the orchestra’s existing “brand.”

Many orchestras are using content for which musicians previously received payment under the Symphony, Opera or Ballet Integrated Media Agreement (“IMA”) or other AFM agreements and which is still in a “rights period” during which the employer is entitled to distribute it via streaming. Other symphonic employers are availing themselves of streaming opportunities pursuant to a COVID-19 IMA Side Letter, which provides flexibility to stream archived concerts via a private link, password-protected site, or to individuals who provide contact information and agree to receive marketing from the employer. Some are taking advantage of both paid-for media and archival streaming pursuant to the Side Letter.

The IMA and COVID-19 Side Letters also allow for the creation and distribution of more informal “promotional” content, including pieces that rely on the over-layering of individual home recordings to generate a virtual ensemble. Individual orchestra musicians (and the numerous musician couples sheltering together) speak and perform directly from their living rooms and home studios, reaching homebound audiences with an unprecedented degree of intimacy, despite the physical separation. These projects have artistic value but function most vividly to reinforce the shared experience of musician and concertgoer, both temporarily exiled from the concert hall. While these conditions are not ideal, these smaller, individual offerings are unique and let our audiences see and hear the talents of our exceptional musicians in a way they probably never have before.

AFM agreements to expand flexibility for streaming during this crisis period are predicated in every case on the employer continuing to compensate musicians pursuant to the terms of the CBA, whether or not services can occur. Orchestras that have over the years accumulated significant recorded archives are taking this opportunity to share historic performances with their audiences. Some are building more robust digital platforms that will also host newly created content when musicians return to their stages and orchestra pits. The current expansion of digital distribution will have a lasting effect on how orchestras and their audiences interact.

Similarly, projects recorded under AFM agreements administered by the Electronic Media Services Division can and have resulted in much needed income for musicians. As EMSD Director Pat Varriale explains in his column this month, re-broadcasts of daytime talk shows and taped performances done under union contracts, as well as documentaries containing clips licensed from signatory companies, have resulted in significant reuse payments to the musicians on those shows, which is a great boon during the current pandemic.

The AFM and its members are also doing their part to help raise funds for their brothers and sisters (both inside the union and in their own communities), whether it be by participating in large fundraising events or by hosting smaller online livestreams. On April 26, a historic all-Canadian special television broadcast, Stronger Together, Tous Ensemble, raised more than $8 million for Food Banks Canada. The 90-minute special—done under an AFM contract—was broadcast on hundreds of TV, radio, streaming, and on-demand platforms and featured nearly 100 Canadian artists, activists, actors, and athletes, including union musicians such as Sarah McLachlan of Local 145 (Vancouver, BC), Geddy Lee of Local 149 (Toronto, ON), Charlotte Cardon of Local 406 (Montreal, PQ), Sam Roberts of Local 406, Randy Bachman of Local 145, and Jann Arden of Local 547 (Calgary, AB), among others.

On a smaller scale, 30-year AFM member Ray Chew of Local 802 (New York City) hosted a four-part virtual series on Facebook Live to raise funds for union freelancers who have been impacted by COVID-19. Each episode featured music by and interviews with some of music’s greatest artists. The series was done in conjunction with the AFM, and was also promoted by the AFL-CIO.

New Performance Reality

Since social gatherings are prohibited across North America, the new performance reality for musicians is digital. Like Ray Chew, many musicians are taking to Facebook and other social media outlets like Instagram, YouTube, Twitch, and more, to not only showcase their music, but to support their fellow musicians and human beings, and hopefully to even make some income.

The Boston Pops Orchestra, under the direction of Keith Lockhart—all members of Local 9-535 (Boston, MA)—recently posted a musical video tribute on YouTube, Summon the Heroes, featuring the work originally composed by John Williams for the 1996 Olympic Games as a tribute to first responders. John Williams, also a member of Local 9-535 and Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA), joined the virtual tribute with a musical and spoken introduction taped from his home studio in Los Angeles.

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra—like so many orchestras in the US and Canada—put on a virtual orchestra performance about one month after quarantines started. They performed the final movement of Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite, and did it under the volunteer promotional provisions of the IMA.

DSO harpist Emily Levin of Local 72-147 (Dallas-Ft. Worth, TX), wrote about it in the Dallas Morning News, and came away from the experience inspired by her colleagues. She stated she expected everyone to just record their parts at home and send them to her for editing, but instead she found the string players worked together to coordinate their bowings, the woodwinds came up with recording systems that allowed them to tune to one another, and players recorded multiple takes and created videos of the highest musical and technical quality.

“They went to extraordinary lengths to make the project a success,” she wrote. This made her realize that her fellow musicians were committed to the same level of artistic excellence they strive for every week while playing live. “That spirit of camaraderie was still thriving in the DSO, even though we had to stay separate,” Levin wrote. “The virtual art we created may be only a taste of the joy that comes from being enveloped by the sound of a live orchestra, but I hope it reminds us all of what we can look forward to experiencing, once we are together again.”

Numerous orchestras across North America are turning to the internet to post virtual concerts to keep their fans happy and their brands alive and relevant. Thomas Derthick, principal bassist with the Sacramento Philharmonic and Opera and president of Local 12 (Sacramento, CA) told Sacramento Magazine that he encourages supporters of the arts to help keep music alive by donating the cost of tickets that have already been purchased back to the respective orchestras.

“That cash will help keep the doors open for the arts organizations. This is true for theater, for dance and for anything else,” he said. “The sooner we can share our work in person, in the flesh, in the room with an acoustic, with people, the better for humanity.”

While virtual concerts are keeping musicians playing, they are not paying the bills or promoting musicians the way gigs did before quarantine.” Derthick said he has seen the “heartbreak” from his fellow union musicians across northern California. “Our local, like so many in the Federation, is facing major challenges as our work dues income has now evaporated. In the meantime, the work continues as we seek PPP monies from employers for our members,” he said.

In an interview with WUTC 88.1 Chattanooga’s NPR station, Taylor Brown, principal bass of The Chattanooga Symphony and Opera and president of The Tri-State Musicians Union, Local 80 (Chattanooga, TN), said how musicians endure the current crisis of their profession depends on their individual situations. Some musicians do nothing but play and perform, while others have additional forms of income that are still viable. Brown is in the latter category, but still, he says, the future is “concerning.”

“When all of this started many of us lost about a month of work in a day, and now it’s stretched on for a few weeks, and I personally have lost five months of work,” he said. “And it takes a long time to get that stuff accrued, to become in demand and go to just so you can have a year of work; and very quickly it went away.”

Brown says that turning to the internet to produce music, as many musicians are, is “helpful” and “a good option to have right now,” but nothing can replace in-person contact, performance, and collaboration. “I’m very concerned about 1) when will we get to go back to work, and 2) what will that look like? Large gatherings are crucial to music-making and art-making. I wonder when will we do it, and will people be hesitant to gather again? I certainly hope not, but it would make sense,” he said.

Guitarist and singer Phil “The Tremolo King” Vanderyken of Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA) also wrote about his concerns in a recent opinion piece on

www.godisinthetvzine.co.uk. “Streaming took away our ability to sell recorded music, and Corona took away our ability to gig and tour for God knows how long. So, strictly speaking, we have lost all our streams of income,” he wrote. “But giving up won’t do. We must find another way. We have to rethink the entire industry … along lines of solidarity and cooperation.”

Vanderyken stated that not only do musicians need to work together, but so do musicians and business owners and tech companies. He believes musicians need to embrace the idea of new business models: co-op venues, co-op labels or management companies, pooling resources to increase efficiency and reduce overhead. Also, streaming rates need to be raised, consumers need to be educated about the economic realities of streaming for musicians, and musicians need to look at owning their own tech infrastructures and start-ups and thereby cut out the companies that give the content creators a pittance as a handout.

Interestingly, just last month, Facebook announced plans to allow users to charge for livestreams, which would provide a way for musicians and other creators to monetize their performances and events on the platform. The company also announced it will be expanding its “Stars” tipping system to musicians, although, as Variety.com pointed out, with a $.01 tip per star, “a bag of groceries will require a galaxy of stars.”

Some musicians have moved from livestreaming on Facebook to creating subscription-based Patreon platforms so they can make some sort of income off their craft. “The response to the livestream has been overwhelming and very touching … but I, and all of my musician friends, have begun to realize that it may be up to a year or more before people are comfortable sitting in a jazz club or a concert hall,” stated Local 802 jazz pianist Fred Hersch when announcing his recent switch to the Patreon platform.

Professor Gigi Johnson of the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music and host of the Innovating Music podcast says the new quarantine reality is rapidly changing the music industry on numerous fronts. The first and most obvious change regards performance venues. Virtual concerts and drive-in concerts—such as those happening in European countries—are the new normal. The “tremendous consumption of online content” is “creating new ways for musicians to connect with fans and audiences often without an intermediary,” Johnson says. This can actually increase artists’ branding, sales, and exposure in ways they may not otherwise have achieved simply by playing live gigs.

However, the new question now is not just when will we go back to live performances, but what will consumers want to do when we can go back? Will outdoor performances become more prevalent because the risk of coronavirus exposure is less than in indoor settings, or will virtual performances be a greater draw because that has become the norm?

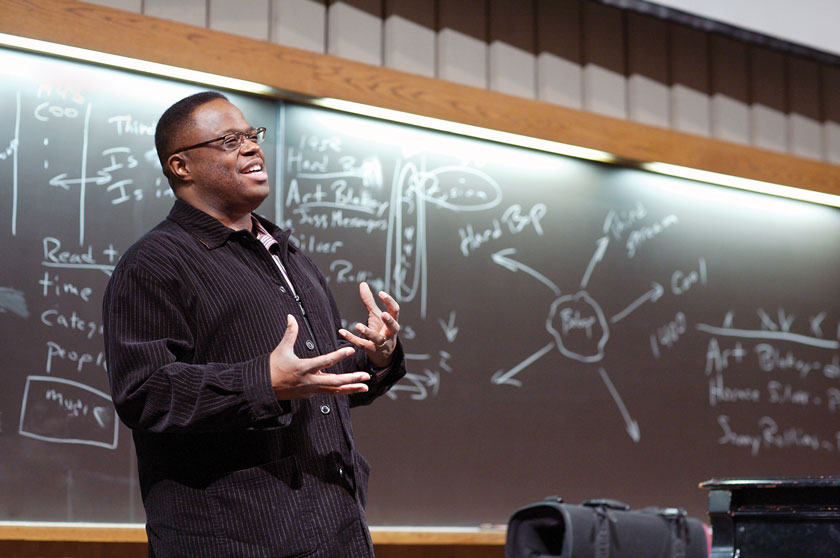

Johnson says she also sees union organizing increasing, especially in European countries, during this time of pandemic because the “really important question” currently for creators is: How do I have a voice in this new environment? She says numerous organizations are now “stepping up” to better serve their members with online availability, training, and community access. This is also leading to a massive transformation of music education in terms of how music is taught, what size and type of audience can be reached, and how to manage online teaching as a growing revenue stream.

Johnson’s advice to musicians during this time is to 1) focus on your mental and physical health, which may necessitate a reconfiguration of your creative processes; 2) reevaluate your skills and don’t be afraid to pick up new ones, especially technological skills, now that so much of music and performance is online; and 3) realize that people are at home and are therefore immensely more reachable. Invest in your “ecosystems”— it’s more important than ever to stay in touch with your colleagues and peers, and thereby expand your audience through artist cooperation and collaboration.