In 2017, David Varnado of Local 433 (Austin, TX) received a string of awards that included an Academy of Country Music award for Fiddle Player of the Year (for which he was also nominated in 2001), the Legend Award from the American Fiddlers Association (AFA), and Fiddler of the Year from the Texas Country Music Association. In the meantime, he was inducted into the Museum of the Gulf Coast in his hometown of Port Arthur, Texas. Since then, he says humbly, “Everything has taken off.” In 2018, he took home the prestigious Johnny Gimble Fiddle Award.

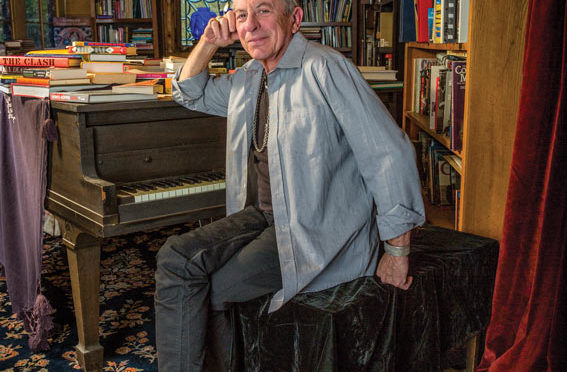

Third-generation fiddler David Varnado of Local 433 (Austin, TX) recently received the Johnny Gimble Fiddle Award from the Country Music Artists’s Association of Texas.

A third-generation fiddler, Varnado knew at five years old what he was destined to do. Looking over his father’s shoulder, he says, “I’d see where he was laying his fingers. That’s how I learned to play.”

A recipient of the Honorable Musician award from the State of Texas (also in 2017) Varnado is an in-demand session musician who also plays mandolin and acoustic guitar. Though versed in reading music, these days Varnado mostly plays by ear. He’s done a lot of studio work, but admits, “I’m most fulfilled by live performance.”

Varnado’s entrée into the fiddling world wasn’t country, but Cajun music. “I cut my teeth on Cajun French music as a little kid. It’s my culture. My mom and dad are from South Louisiana. It’s happy music. I think it has everything to do with the lifestyle—the sound is exciting.” Years later, in October 2016, Varnado received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cajun Music Association.

His dad happened to be good friends with Rufus Thibodeaux, the “king of the Cajun fiddle players,” who played for Bob Wills, Neil Young, and Grand Ole Opry star Jimmy C. Newman. Thibodeaux became Varnado’s mentor and taught him from age 12 to 17. He and his father would make the two-hour drive to Lafayette every Friday. The young Varnado would play Friday and Saturday night gigs with Thibodeaux and study with him during the day. It was creative, advanced fiddle music, with emphasis on Cajun and Texas swing. He learned country and Cajun stylings, while sharpening his harmony-playing skills.

Thibodeaux introduced him to Nashville when Varnado was 16 years old, where he joined Local 257. Around the same time, he met Johnny Gimble, who Varnado still considers: “The greatest western swing fiddle player to walk the face of this earth.” With Gimble, he quickly mastered techniques in advanced finger noting, bowing, and sustaining a rhythmic lift, and learned how to back up a singer in a swing band.

From 1989 to 1991, Varnado lived in Japan performing in the play, One Reel. He had an apartment in Tokyo and went back and forth to Texas. The show eventually played in Lafayette and Crowley, Louisiana. In 1991, Grammy award-nominated Cajun accordionist Jo-El Sonnier called Varnado. “He wanted to know if I wanted to do the Nashville Now show with Ralph Emery.”

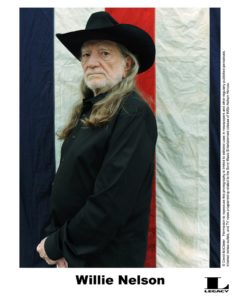

About three years later, his friends in George Strait’s band (Ace in the Hole of Local 433) encouraged him to move to Austin. Varnado explains that Nashville seems to have become more of a hub for rock ‘n’ roll. He says, a lot of what they call country is actually Southern rock, which he likes a lot. But, it’s not authentic country music. For that, he says, “Listen to Mark Chesnutt, Randy Travis [of Local 257], Marty Robbins, Vern Gosdin, or Gene Watson [of Local 65-699 (Houston, TX)].”

A longtime supporter of the union, Varnado says, “My dad was an iron worker and welder. I’ve watched him fight for union work and wages. You get great wages with the union. I’ve done The Jay Leno Show and Conan. You couldn’t get on those shows unless you were union. I’ve always liked being part of the musicians union because it brings people together as one. If something goes wrong, I call my union office and they’ll fight for me. They’re going to make sure I get my money.”

Among his most memorable experiences was performing with the late Chris LeDoux—a prolific songwriter, musician, and world champion bareback rider, to boot—whom Varnado says was one of the most generous people he’s known.

It was the late Johnny Paycheck who introduced Varnado to traditional honky-tonk. “He put me on the map and got me noticed at the Grand Ole Opry. I’ve played a lot of fiddle, a lot of fiddle kickoffs. I loved doing the late shows, but it was playing the Grand Ole Opry that made me feel like I made it. It’s to the musician what Hollywood is to an actor,” he says.

Since then, he’s played the Opry numerous times, notably with Ty England and Loretta Lynn of Local 257. Between gigs in Austin and Nashville, Varnado stays busy. In addition, he’s performing with George Dearborne with whom he last performed at age 16. “I’ve come full circle,” Varnado says.

Recently he committed to working with award-winning coproducer and engineer Don E. Meehan of Local 802 (New York City) on a solo CD, which will include vocals, instrumentals, and traditional country and western fare. It looks like the much-celebrated sideman may now take a turn at center stage.