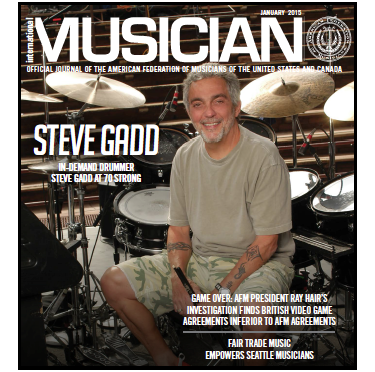

If there is one drummer you could say has literally kept the beat for “everyone,” that drummer would likely be Steve Gadd, a member of Local 802 (New York City). And when asked about all the different genres of music he’s played, and diverse acts he’s worked with, he approaches the topic very matter-of-factly.

If there is one drummer you could say has literally kept the beat for “everyone,” that drummer would likely be Steve Gadd, a member of Local 802 (New York City). And when asked about all the different genres of music he’s played, and diverse acts he’s worked with, he approaches the topic very matter-of-factly.

“I’ve been a freelance player my whole life,” he explains. “I love to play music with people who love to play music, so that’s the way I approach it.”

From his earliest days of drumming, Gadd took an eclectic approach to learning. “I listened to a lot of different drummers and copied them—Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Jimmy Cobb, Elvin Jones, Tony Williams, and Jack DeJohnette [of Local 802]. To this day, when I hear someone play something I like, I copy them,” he says.

But, while watching, learning, copying, and taking lessons from a lot of different teachers, Gadd was also developing his own style. “The last teacher that I had, John Beck, always encouraged me to do things in a way that felt comfortable for me. I think that’s very important for young people. It’s okay to copy, but they have to find a way to make it feel comfortable for them. That’s what will make the most sense musically.”

However, he explains, becoming a successful session drummer is not just about learning your chops and developing your own style. “You’ve got to be able to fit what you are doing with other people; it’s not about feeling like your way is the only way,” he says. “It’s about making your way work with whoever you are playing with and making the music feel the best you can. It’s a give and take thing.”

Gadd takes on each job with the professionalism of an experienced musician whose focus is keenly on the end product. “For me, before anyone starts talking about the music, I would rather hear the demo or have them play the song; until you hear the song, there is nothing to talk about,” he says quite simply. “I think that listening before talking is important because then you’ve got something you can relate the words to.”

50 Ways to Groove on 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover

His humble, patient, and accepting approach to music leaves Gadd’s mind open to try many different possibilities, until everyone is pleased with the result. For example, one of Gadd’s most talked about and well-recognized grooves happens in the intro to Local 802 member Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover.” Gadd explains how he was just noodling when he happened upon it.

“We had been working on that song for a while, and the chorus part fell into place easily, but the first part wasn’t really feeling the way it should and we tried a few different things,” he says. “A lot of times I would stay in the drum booth while Paul and Phil [Ramone] were discussing what they wanted to do and I practiced different things. I was practicing a little military beat and Phil heard it and thought we should try it for the first part of the song. We just sort of stumbled on it by chance.”

Among the other “pinnacle” Gadd recordings are his solo work with Steely Dan on Aja, and recordings he’s done with Local 802 members Chick Corea and Bob James. “I feel very fortunate to have been able to have done what I’ve done with as many people as I’ve been able to play with; on a certain level, they are all special,” he says. “When I go in with everything I’ve got and it has an effect on the industry, I’m proud of it.”

However, Gadd explains that he isn’t one to look back on his accomplishments, however remarkable. He is more affected by when something he’s done has meant something to other people, especially other drummers. “Those are the things that are special to me,” he concludes.

From the early days of his career, Gadd made it a point to not get pigeonholed into one specific genre, but rather to take on new and diverse projects as they came along. “I like variety; I am challenged by that,” he says. “When I first got into recording there were certain things that I wasn’t comfortable with, but I kept trying and I was able to find a comfort level in a lot of different styles.”

Another Gadd key to building your freelance career: be reliable. “When you accept something, you give your word that you are going to do it, if something else comes up that you would have rather done, you have to stick with your word and your honor,” he says. “That is a basic rule. However, business-wise, you can’t afford to say ‘no’ to certain things. If you are a person of your word, then people understand when things happen and you can work it out.”

Have the Right Gadditude

And then there’s attitude. “If you are in the studio and you want people to call you back, a lot of that has to do with your attitude,” he continues. “If you are on the road, you are playing the show, you might be playing for two or three hours, but you are spending the other 20 hours of the day traveling with people. All of that enters into it: how you get along with people, how much of a team player you are, and if people start to get tired and things get dark, shine some light on it because, in the long run, that’s going to affect the music.”

And then there’s attitude. “If you are in the studio and you want people to call you back, a lot of that has to do with your attitude,” he continues. “If you are on the road, you are playing the show, you might be playing for two or three hours, but you are spending the other 20 hours of the day traveling with people. All of that enters into it: how you get along with people, how much of a team player you are, and if people start to get tired and things get dark, shine some light on it because, in the long run, that’s going to affect the music.”

“It’s not just about the playing; it’s about showing up on time, doing your best, and trying to understand what people, like the producer, are verbally trying to get you to do on the instrument. That takes a lot of energy. If you try something and it’s not really the right thing and they want you to try something different, after that happens a couple of times, you can start to get a little paranoid. You have to remember why you are there and remember that the guy who is talking to you about the music is not a drummer, so it’s not easy for him to explain what he wants,” he says. “Just give 110%.”

Throughout his entire career Gadd has had the AFM by his side. “All the guys I work with are in the union,” he says. “I am happily a member and will continue to be. And a testament to that is that I’ve gone through my whole career and not really had any problems. I can’t imagine not being in the union.”

Not living in a big recording center like L.A., these days Gadd, a resident of Phoenix, Arizona, is not involved in recording as much as he once was and this has allowed him time to create a few of his own projects. The Steve Gadd Band (with Local 47 members Michael Landau, Larry Goldings, Walt Fowler, and Jimmy Johnson) released its first album, Gadditude, in 2013 and just finished recording its second album, 70 Strong, scheduled for release April 2015. “I’ll be 70, so that’s where that comes from,” he explains.

Gadd has also been putting together his third album as the Gaddabouts with Edie Brickell. “That was her idea and it’s with Pino Palladino [of Local 47] and [Welsh guitarist] Andy Fairweather Low. It’s all Edie’s songs,” he says. Other 2015 projects will have him working with Local 802 member James Taylor during March and April and Eric Clapton later in the year.

Regardless of whether it’s his project or someone else’s, Gadd says his approach is the same. “If I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing, then people around me sound good. It’s not about drawing attention to me, it’s about playing in such a way that everything flows and everybody feels comfortable,” he concludes.

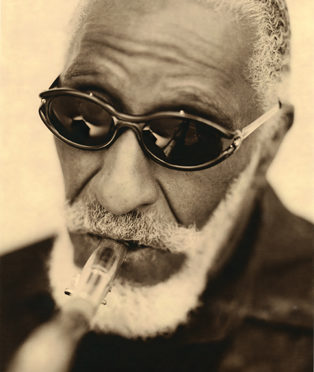

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.