When talking to musicians about their lives and careers, the phrase that always occurs during the conversation is: “…and then COVID hit.” It’s been a life- and career-changing event, and one that has allowed/forced musicians to spend time on special projects. For Marta Bradley—bass player and secretary-treasurer of Local 161-710 (Washington, DC)—that project was the creation of a 6-foot-by-7-foot quilt depicting images related to the year 2020 and the social justice events and aspects of that momentous time.

“I’m a quilter, but not a quilt artist. Generally, I make blankets and they’re meant to be comforting for friends and family. There’s always love behind every single one, which I make purposefully for somebody with them in mind,” she says. “It’s the art of the love that goes into it. It brings comfort not just in the way it feels, but hopefully in the gift of making it and that it’s special to each person.”

“But then COVID hit,” she continued, “and there were no gigs so there wasn’t a lot to do.” Being active in her church, which had congregants worshipping remotely, Bradley took the suggestion of the pastor that everyone create a special place to worship in their homes. Bradley made a table runner that represented the Pentecost—and then the George Floyd incident happened. The event and its ramifications on social justice in the US caused Bradley to decorate the runner as an homage to the growing Black Lives Matter movement. She created a map of the US in black, on which she sewed over 50 names of people murdered this year. She then added portraits of the victims most in the news last year: George Floyd, Brianna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

“I’m not an artist; they weren’t meant to be portraits. It was more of a way for me to fit what this country has done over the years, and the horrors of systemic racism, and understand it,” she says. “It was a way for me to sit with it and to worship and say their names and learn about them and read their stories—to put them in a quilt and put them on an altar and pray their names.”

That was Bradley’s beginning in quilting her way through the pandemic and all the social injustice and racial tensions occurring through the country last year. She was also sewing face masks for the pandemic, and, after accruing a box of scraps, she thought maybe she would make a “scrap quilt” when she was done. During this time, one media photograph particularly resounded with her: A photo of seven-year-old Kai Ayden standing in front of a line of riot police, raising his fist while demonstrating in Atlanta on May 31. She decided to sew that image into a quilt block—“and then it just got going,” she says.

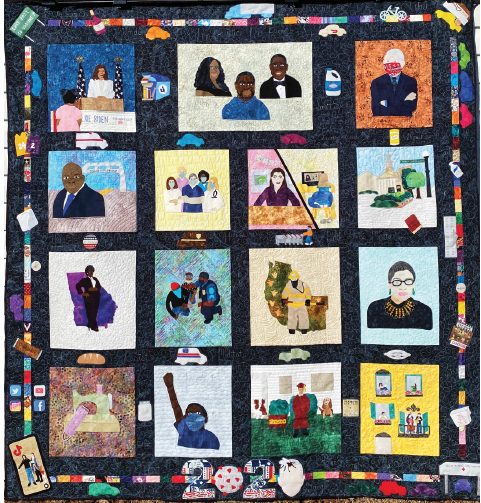

After that, Bradley made quilt blocks of people and events making news as heroes of 2020. Ultimately, she made 15 blocks, depicting images such as portraits of deceased Congressman John Lewis, deceased Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, Dr. Anthony Fauci, and Georgia Democratic politician Stacey Abrams. Bradley also made images depicting healthcare workers, firefighters, a police officer kneeling with BLM protestors, a teacher and student communicating through Zoom, her son graduating from high school, and she and her husband (also a musician) performing music on a balcony while neighbors listen.

“I wanted it to be something that showed, as time went on, not just 2020 but the heroes of 2020 and what makes us carry through and grow stronger as we go forward,” Bradley says.

The 15 blocks were put on a black background, with the lines in between them all representing roads, surrounded by a border made of scraps from her face masks (from her initial idea). On the roads and around the border are also images of other items: cars, people, food, medicine, and more. Of course, a union label was also included (right under Justice Ginsburg).

In the end, Bradley estimates it took her close to 250 hours of work to create the quilt. “It was something that I started that I couldn’t put down; I felt driven to do it,” she says. “It was a way to sit with each of these things, to sit with all of it, and find peace through sewing. I missed my friends, playing with them, creating music, and this was a way to put that energy into something.”

Bradley completed her quilt on December 27, 2020. She has no specific plan on what to do with the quilt, she says, but it will probably be hung on the wall in a guest bedroom in her house. “It won’t go on the bed. I have dogs. I put too much work into it for that,” she says with a laugh.

Marta Bradley, secretary-treasurer of Local 161-710 (Washington, DC), poses with her social justice quilt, which depicts the events and heroes of 2020. She spent more than 250 hours of work on it.