In a career spanning more than six decades, Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA) member Art “Poppa Funk” Neville is a

legend of the music scene in one of the world’s most musical cities. Though Art was the first Neville to launch a career in music, today the family name is synonymous with the New Orleans sound. Art’s three siblings—Charles, Aaron, and Cyril—all eventually went into music.

“Being born and raised here, I picked up on the rhythm of the city from a very early age. It’s something you can’t get away from—the people, culture, food, and music shape everyone here differently,” he explains. “I’ve been able to carry those values of loyalty, love, and creativeness with me all my life.”

When Neville first formed a doo-wop group in high school, it was just for fun, and also to meet girls, he confesses. “I was steeped in doo-wop early on—the Clovers, the Spiders, as well as Fats and other local favorites. We used to sing in the bathroom at school (the acoustics were good) and we’d get together at night in the park and practice. It was really the beginning of making music seriously.”

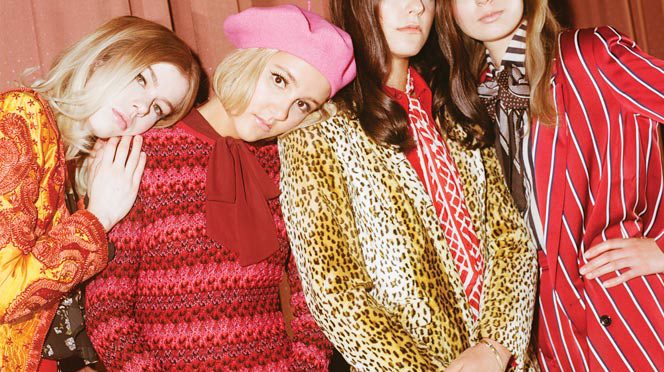

The Hawketts

Around age 17, Neville joined his first real band, The Hawketts. The group was looking for a piano player, and through a friend of a friend, Neville was invited to join. “I didn’t know who they were at that point. I said, ‘Sure,’ and my mother and father said, ‘Yeah, go ahead.’ And the rest is history.”

Around age 17, Neville joined his first real band, The Hawketts. The group was looking for a piano player, and through a friend of a friend, Neville was invited to join. “I didn’t know who they were at that point. I said, ‘Sure,’ and my mother and father said, ‘Yeah, go ahead.’ And the rest is history.”

It was shortly after joining the band, that Neville made his classic recording of “Mardi Gras Mambo.” At the time, it didn’t occur to him that it would become a seasonal anthem. “I never thought it would [still] be around to this day,” he says.

The Hawketts became the hottest band in New Orleans and the surrounding area. “We played for every type of function—sororities, fraternities, plus night clubs, small and large,” he says. When most of the original members left, Neville kept the band together. After being drafted into the Navy Reserve’s active duty for two years, including a stint as a cook on the USS Independence, the musician jumped right back into the New Orleans music scene, not missing a beat.

In 1966, Art’s brother Aaron had his first major hit, “Tell It Like It Is,” and they went on tour together. Soon after, Art put together a seven-member group that included his brothers: Art Neville and the Neville Sounds. In 1967, when they were hired to play a coveted gig at the Ivanhoe bar in the French Quarter, they had to scale-down to fit the venue.

The Meters

That marked the launch of The Meters with bassist George Porter, Jr., drummer Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste, and guitarist Leo Nocentelli. They soon became the house band for Allen Toussaint’s studio. They backed a long list of local and international musicians including Dr. John, Paul McCartney, Robert Palmer, and Patti Labelle.

The group released eight albums of distinctive New Orleans sounds blended with funk, blues, and dance grooves. Together through the 1970s, The Meters toured the globe, including opening up for The Rolling Stones on their Tour of

the Americas.

A family steeped in New Orleans culture and traditions, Art’s parents and uncle, “Chief Jolly” George Landry, longed to see the Neville brothers work together. Landry and his nephews released The Wild Tchoupitoulas in 1977, a sort of aural documentary of Mardi Gras Indians. Following their mother’s death in the late 1970s, the brothers formed The Neville Brothers. The next year they released an album and performed and toured together until 2012.

The Neville Brothers

Through all those years, the brothers continued their independent careers and work with other groups. In 1989, Art was involved with an informal Meters reincarnation at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival that included Porter and drummer Russell Batiste, Jr. Encouraged by that performance, the funky METERS was officially launched in 1994 with Neville, Porter, Batiste, and guitarist Brian Stoltz.

Through all those years, the brothers continued their independent careers and work with other groups. In 1989, Art was involved with an informal Meters reincarnation at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival that included Porter and drummer Russell Batiste, Jr. Encouraged by that performance, the funky METERS was officially launched in 1994 with Neville, Porter, Batiste, and guitarist Brian Stoltz.

“We’re still out there touring and playing festivals. It is exciting to still see the fans that have been with us for a long time, and now young fans discovering our music. It’s also exciting to know the music has stood the test of time,” says Neville. “Last year, The Meters’ ‘Stretch Your Rubber’ was used in a Nationwide commercial and right now ‘Hand Clappin’ Song’ is being in the new Google Pixel ads.”

Through all these years, Art Neville has been a loyal AFM member. “I remember when we first performed on television and filling out the paperwork. I was happy to be able to say, ‘Yes, I’m an AFM member,’ and I was also happy to get paid accordingly and properly. I’m a proud AFM member to this day,” he says. Neville’s AFM membership goes back to the days of segregation, and black Local 496, which combined with Local 174 in 1968.

During segregation, touring outside of New Orleans was particularly perilous, he recalls. “It was interesting because, in New Orleans, playing music was the one thing we all did together: black musicians playing with white musicians, or musicians of any ethnicity. It was always about the music, not what color you were.”

But, in other places it wasn’t like that and touring was scary. “It was treacherous. We wanted to play music, but we always had to be aware of our surroundings, whether we were playing school dances or night clubs,” he says. “I remember playing a show and when we returned to our station wagon there was a note under the windshield wiper that read: ‘The eyes of the Klan are upon you.’ That was very scary.”

“One dance, in particular, our drummer forgot his snare drum so we had to go back home and get it,” he says. “While we were gone, the stage in the auditorium was blown apart by dynamite that had been placed with a timer under the stage. Had we gone on, on time, we wouldn’t have been around to tell about it!”

Looking back on his long career, Neville says he has no real regrets but does wish he had finished school. “The one thing I would tell my younger self is: ‘The music will be there, and you can do both,’” he says. “I’m very happy and blessed with all the opportunities I’ve had and created on my own.”

Neville says he’s not sure if the Neville Brothers will get another chance to perform together. “Maybe we’ll do some more shows in the future, while we’re all still here, I Neville say never!” he says. “I’m most proud of fulfilling my uncle’s wishes to keep the family and music alive. I think, between The Meters and The Neville Brothers, we made it happen.”