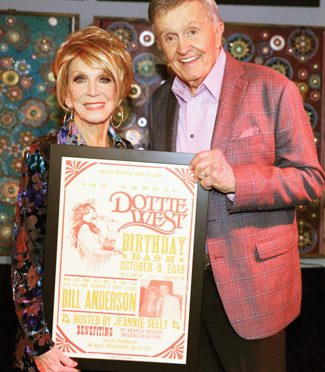

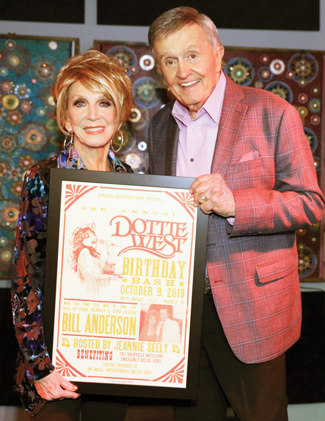

The third annual Dottie West Birthday Bash recently raised more than $28,500 for the Nashville Musicians Association Musician’s Emergency Relief Fund. The event, hosted by 52-year member of the Grand Ole Opry Jeannie Seely, included musical performances by Seely and Local 257 members Tim Atwood, Jon Randall Stewart, Buddy Cannon, Michele Capps, and Danny Davis.

In addition to celebrating Dottie West’s birthday and honoring her, the event also honors a musician or artist who has made an indelible impact on country music.

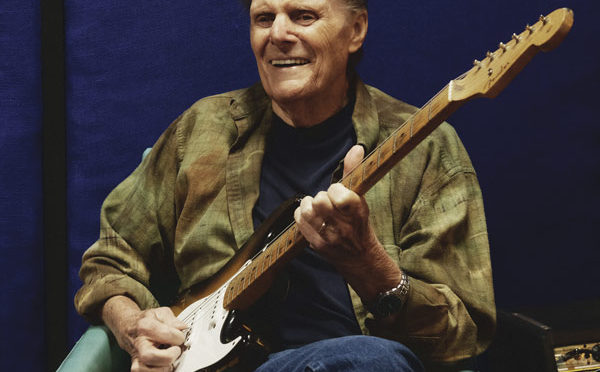

This year the event honored Grand Ole Opry, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, and Songwriters Hall of Fame member Bill Anderson.

Nashville Musicians Association Musician’s Emergency Relief Fund helps Local 257 members in financial need due to medical and emergency issues that prevent them from working.

Donations to the Local 257 Musician’s Emergency Relief Fund can be made online at www.nashvillemusicians.org.