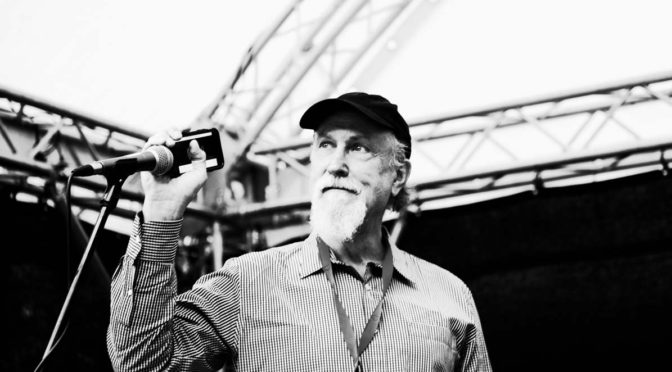

Just after this photo was taken in 2010, Nasar Abadey of Local 161-710 embarked on a month-long Supernova tour to East Africa sponsored by the US State Department. (Photo credit: Jos A. Beasley.)

This month, Nasar Abadey, drummer, bandleader, and educator will receive the DC Jazz Festival Lifetime Achievement Award, alongside Cuban pianist Chucho Valdés.

Abadey, of Local 161-710 (Washington, DC), has played with masters of the jazz world, among them fellow DC union members Andrew White and Lennie Cuje. Abadey was tapped by Sun Ra in the early 1970s in New York City. “I was sitting in with McCoy Tyner’s band at a club called Slugs’ on the Lower East Side. When I left the bandstand, Sun Ra’s manager he asked if I was interested in playing with Sun Ra. I said, ‘Well, sure.’ He said, ‘Meet me at Penn Station tomorrow at noon.’”

Named Best Drummer in Jazz in 2011 by the Washington City Paper, Abadey went on to play with other greats, like Stanley Turrentine, David Sanchez, Charlie Rouse, Gary Bartz, Cyrus Chestnut, Gregory Porter, Frank Morgan, Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Jones, and Bobby Hutcherson.

Back in 1976, Abadey was playing gigs in his hometown of Buffalo, New York, when he got a call out of the blue to play with Ella Fitzgerald. Throughout his long career, he’s built a solid reputation as a sideman with many groups. He has recorded and performed with innovators Malachi Thompson and Joe Ford (saxophonist in Abadey’s group Supernova).

With Supernova, Abadey performs jazz steeped in hard bop, modal, and avant-garde, often incorporating traditional African rhythms, bebop, fusion, Afro-Cuban, and Afro-Brazilian influences. He is also founder and artistic director of the 16-piece band Washington Renaissance Orchestra (WRO).

For a time the family lived in Buffalo with his mother’s cousins, the Dunlops. Frankie Dunlop was the prodigious drummer who famously played with Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, among others. He says that Frankie practiced every day in the attic and became one of his main influences. Abadey was just six years old when Frankie put a set of sticks in his hands and showed him how to start playing.

“I didn’t know who he was. He left Buffalo when I was seven years old and I didn’t see him again until I was 13. I had a transistor radio and I heard the song ‘Monk’s Dream’ on a jazz program and I said, ‘Wow, the drummer sounds like my cousin Frankie.’ When they announced the group members, the drummer was Frankie. I remembered his sound.” They reconnected when Abadey moved to New York City. He’d often visit Dunlop in his Harlem home where Dunlop would tell him stories about his years playing with jazz legends.

Abadey who has lived in Washington, DC, since 1977, embarked on his own career in jazz that placed him in a class all his own. Drawing on influences from powerhouse drummers such as Tony Williams, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, and Elvin Jones, he built a solid career as an artist and teacher. Now, he is one of the mid-Atlantic region’s premier jazz drummers.

In 2006, Abadey was asked to join the faculty of the Peabody Institute. “The process of education has been an organic kind of thing. Each semester, each year, I find myself incorporating more into what I teach and how I teach. As a result, I become a better musician and drummer,” he says.

“I like to think of music as going in many directions simultaneously—poly-directional.” Which he calls “multi-D”: multi-dimensional and multi-directional, a term that is also easy to pronounce and remember in any language. “It helps the listener understand that they are experiencing various dimensional realms while listening to music. I like to think the music is more complex than traditional forms of jazz.”

Abadey invokes plenty of John Coltrane’s automatic technique, which he says allows the music to lift off into a spiritual zone. “The unknown can always render something new because it is the unknown. How your spirit interacts with the creative endeavor,” he says.

He encourages his students to go to his gigs to hear him play so they know that what he’s teaching is not abstract. He adds, “It’s also important to articulate the source of a particular rhythm when I play it and understand it when I hear it played. I look at Africa as the source and different rhythms from Cuba, Brazil, Puerto Rico.”

Throughout his career, the union, which he joined at 18, has provided support. He says, “With the union, you’re associated with an organization that has what every musician needs to indulge their art and the backing to make sure we’re getting proper wages, benefits, and pension. When you get gigs, you will not be paid below a certain amount. All those things are in place. Plus, you have legal representation.”

In addition to Supernova and the Washington Renaissance Orchestra, Abadey leads the Renaissance Trio (rhythm section) and the Washington Renaissance Orchestra Octet. In between gigs this summer, he is working on a project writing for strings for his 11-piece Supernova Chamber Orchestra.