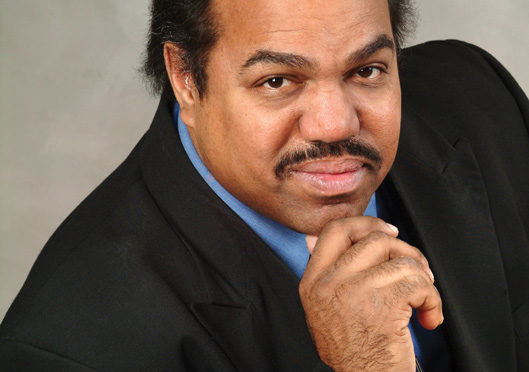

Lennie Cuje has been a fixture on the jazz scene for more than 60 years. A Local 161-710 (Washington, DC) member since the 1950s, the celebrated vibist has experienced life on a grand scale—in music, in war, and in two homelands.

Lennie Cuje has been a fixture on the jazz scene for more than 60 years. A Local 161-710 (Washington, DC) member since the 1950s, the celebrated vibist has experienced life on a grand scale—in music, in war, and in two homelands.

Born in 1933 in Giessen, Germany, (40 miles north of Frankfurt) Cuje grew up during the Nazi regime. He was enrolled in an elite music school at nine years old. Like all German boys, it was compulsory to join the Hitler Youth, making the pledge, he says, “‘born to die for Germany.’”

Near the end of WWII, when there was a shortage of soldiers, he and other 12-year-old boys were drafted by the SS to train on MG-42 machine guns. His conductor father got into trouble with the Nazis for refusing to play preferred music of the regime and was exiled to the front to drive a truck. After his school and city were bombed out, the family was evacuated from Frankfurt and became separated. Cuje and his classmate and friend Ulrich found themselves in the hands of the French. They were spared internment in POW camps and found refuge at a local convent to live out the remainder of the war.

The story of the boys’ journey in 1945 across Europe and a decimated Germany in search of their mothers is the subject of a play that recently aired on Hessian Radio Frankfurt and Kultur Radio Berlin. Ulrich, who made a career as an actor and in radio back in Germany, was instrumental in compiling their story, which has aired in Germany four times already in the last year. A recurring theme in the play is freedom, as Cuje explains. “We went to sleep in a barn and were surprised to wake up to realize that we were still free.”

At the end of the war, Cuje was going through an American sentry post when he first heard jazz. “I heard that strange music in the guard house, which I thought was African. It was exciting; it just grabbed me,” he says. The tune that enthralled him—which would define the rest of his life—was Lionel Hampton’s “Flying Home.”

Back in Frankfurt, his family subsisted on meager rations. He traded on the black market to provide for them. Cuje says, “The hunger, poverty, coldness, it was a part of our life. The currency was cigarettes.”

When Cuje immigrated to the States in 1950, he was already well versed in American jazz standards, owing to the jazz shows on American Armed Forces Radio. He says, too, that he formed the first German baseball team, the Frankfurt Juniors. “Baseball and jazz—that was going to be my life.”

With the support of his aunt who had been in the US since the 1930s, he embraced everything American. He was drafted into the Air Force in 1952, later attending East Tennessee University to continue his music studies. He learned to be American, Cuje says, “penny loafers and all.”

“When I left Germany, I left everything German behind,” he says. “The way they taught it, Germany was the only country that could save the world. Reality for me was a lie. By 1945, when it all collapsed, my friend Uli, he knows. Suddenly, we realized we’d been lied to for the first 12 years of our lives. I didn’t want to have much to do with Germany. As a Hitler youth, I had to take an oath to die for the swastika. And here, in the air force—I had to swear to two flags. It makes you think about a lot of things.”

“Jazz was like medicine for the mind and it brought a feeling of freedom. Baseball had that same feeling—freedom!” His late wife, Reneé, a professor of German at American University, convinced him that he needed to revisit his past in a profound way. She encouraged him to re-establish his Frankfurt school connections.

“Jazz was like medicine for the mind and it brought a feeling of freedom. Baseball had that same feeling—freedom!” His late wife, Reneé, a professor of German at American University, convinced him that he needed to revisit his past in a profound way. She encouraged him to re-establish his Frankfurt school connections.

In 2016, after 71 years, Cuje and his old friend, Uli, were reunited. “We always wondered whether the other made it out alive. When Uli found out I played the vibraphone, he was amazed. Uli said, ‘My god, Lennie Cuje is a known jazz musician in America.’”

Cuje began speaking German with his wife again, which he had not done in many years, and it helped him reconcile past and present. “It brought peace to me. It was important for my musical career. I was able to put the two Lennies together,” he says. “That’s when I started my career all over again, from the beginning.”

When he began playing in the 1950s, Cuje was one of the few white players on the U Street corridor of Washington, DC, part of the Chitlin’ Circuit. He says, “I had all black cats in my band so I played on the black scale, which was less than the white union. We’d go from one juke joint to another and pass the hat. My nickname was ‘snowflake’,” he laughs, adding, “Those were glorious days for me.”

In 1960, he joined the Buck Clarke Band with Charlie Hampton, Duane Alston, and Billy Hart and recorded with Clarke for Argo Records. At the height of the avant-garde movement in 1963, like many musicians, he made an exodus, anxious to join leading players like Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and especially John Coltrane in New York City. He landed his first gig with Dave Figg and Paul Bley, whom Cuje knew from DC, and studied with renowned vibists Warren Chiasson of Local 802 (New York City) and Dave Pike. He played gigs with David Amram of Local 1000 (Nongeographic), Philly Joe Jones (Miles Davis’s drummer), and Larry Coryell.

Later, back in Arlington, in 1983, he began a 10-year engagement at DC’s famous One Step Down with Nasar Abadey of Local 161-710 and at Baltimore’s Harbor Court Hotel with Lou Rainone for 20 years. Spike Wilner of Smalls Jazz Club in New York City became a good friend and frequent collaborator and even now, on occasion, he plays vibes with Chuck Redd, with whom he’s performed over the last 30 years.

In 2000, Cuje’s artistic vision took him in another direction. After Cuje’s aunt, Magdalena Schoch, died, he found poems and a handwritten manuscript of music in the family’s basement, which were composed by Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy (grandson of composer Felix Mendelssohn) and dedicated to Cuje’s Aunt Lena.

Cuje explains that she was Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s protégé. “It was a love affair that never was. They were partners who formed the first German international law office in the late 1920s. She was a professor at Hamburg University until 1934, when Mendelssohn Bartholdy—a scholar and advocate for peace—fled Nazi Germany for England. He died there in 1936, and the Nazis warned that if Lena attended the funeral, she’d lose everything.

With Reneé’s help he arranged the music titled “Lieder for Lena,” which premiered in West Berlin’s Mendelssohn House. “We decided to bring it to life in honor of my aunt who brought me to this country so I could live my dream,” says Cuje.

At 85 years old, Cuje calls himself a “civilian.” He’s retired the tux, but plays local gigs and occasionally when his old friend Spike Wilner comes to town. Cuje has come full circle, embracing everything American, German, and jazz.

His favorite baseball team is the Yankees. “I love to see a good baseball game,” he says. “It’s like jazz, you’ve got the pitcher and the batter and when that ball hits the wood, everything goes into action, like a band. It’s wonderful.”