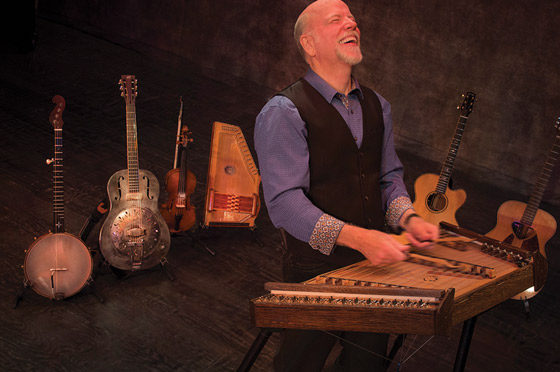

Marlène and Jerry Tachoir of Local 257 (Nashville, TN) with their instruments. In the jazz band the Jerry Tachoir Group, led by Jerry, the vibraphone is the lead instrument. The group performs original music throughout the Nashville region, across the US, and Canada.

While a vibraphone is not often thought of as a lead instrument, that is how Jerry Tachoir of Local 257 (Nashville, TN) conceived his band, the Jerry Tachoir Group. The group also features his wife, pianist and composer Marlène Tachoir, bassist Roy Vogt, and drummer Rich Adams, all members of Local 257.

“As a vibes player, I’m forced into a leader role, since most musicians and bands seldom consider hiring a vibes player to replace a keyboardist or guitarist,” he says, explaining that the most difficult thing is proving how versatile an instrument it is. The vibes have become closely associated with jazz, but at clinics Tachoir tells students he can play anything—country, Latin, classical.

“You have to be creative, to create job situations that allow the vibraphone to be used, or your phone will never ring,” says Tachoir. “Once people hear it and realize I can play what a piano player or a guitar player can play—chords, lines, counterpoint, whatever you need—it’s cool. It’s such a novelty instrument it piques curiosity. When you roll it in, they either think it’s the dessert cart or a gurney.”

Like legendary vibist Red Norvo, Tachoir uses a four-mallet technique, with two mallets in each hand. Other influences include pianists Bill Evans and Chick Corea of Local 802 (New York City). Tachoir says he tries to apply his four-mallet technique to a three-octave aluminum bar instrument and play as a pianist. “My left hand is my accompanist, my right hand does the soloing, and the other mallets fill in chords with additional notes.”

As a young classical percussion player growing up in the Pittsburgh area in the ’70s, Tachoir was known as the “mallet guy.” He performed with many orchestras, namely the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony, Wilkensburg Symphony, and the International Orchestra in Switzerland. Tachoir attributes his solid foundation in a range of percussion to his teacher, Eugene “Babe” Fabrizi, who insisted that his students become well-rounded percussionists, not just drummers. Because of Fabrizi, Tachoir learned all the percussion instruments: xylophone, marimba, vibes, tympani, and hand percussion.

In 1972, Tachoir had a chance meeting with vibraphone virtuoso Gary Burton at a jazz festival where Local 802 (New York City) member Herbie Hancock was playing. Tachoir had never seen or heard anything like it. He was struck by the spontaneity and camaraderie of the jazz players—in stark contrast to the conventions of orchestra playing. “Herbie Hancock would play a line, [bassist of Local 802] Ron Carter would respond. It was the communication I picked up on. They were creating it on the fly, improvising. They were laughing, smiling,” Tachoir remembers. After that show, he immediately went out and bought Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew.

Tachoir told Burton he wanted to learn more about jazz improvisation, and Burton suggested he study with him at Berklee College of Music. Once Tachoir realized he could transfer rhythm skills and play melodies and chords, he was hooked. The tuned bar side of percussion became his emphasis. “I became a mallet player devoted to jazz,” says Tachoir who designed his own degree program in applied vibraphone and mallet percussion, graduating Berklee in 1976.

Now a Grammy-nominated artist, band leader, and author of books on method and approach to the vibraphone and marimba, Tachoir is considered one of the foremost authorities on vibes. He’s recorded with his friend Danny Gottlieb of Local 257 (a Pat Metheny Group veteran) and the late session great Tom Roady, among others.

The Jerry Tachoir Group tours the US, Canada, and Europe, with stops at jazz events like the North Sea Jazz Festival in Rotterdam, the Montreux Jazz Festival, and the International Festival de Jazz in Montreal. Marlène Tachoir, a prolific composer, writes the group’s original music. A native of Quebec, she studied classical organ at the Quebec Conservatory.

“Talk about vibes not being popular,” Jerry jokes. “You don’t carry your classical pipe organ to gigs!” At Berklee, where the two met, Marlène switched to piano and composition. “Her piano playing is unique and complements my busy vibes playing,” he says. “It just works.”

He also credits Marlène’s perfect pitch and ability to scat sing with adding “a wonderful nuance to what has become our signature sound.” Jerry explains, originality is at the core of the group’s identity. “We’re going for a certain style, a composition that works with the band that’s identifiable with us.”

It’s a challenge to write for the vibraphone, but after nearly 30 years working alongside her husband, Marlène now imagines her compositions in terms of the way they would be played on the vibraphone. Her styles are varied: jazz, swing, a lot of blues, Latin, classical elements, and occasionally rock. As independent artists, she says, “We have to make things happen for ourselves.” Of their partnership, she adds, “It’s nice to have an ally.”

Her recent concerto, Jazz Mass for World Peace, was performed by the Jerry Tachoir Group for the International Day of Peace. Indeed, she views peacemaking as part of the musician’s role, saying, “Hopefully we reach people through music.”

In addition to numerous concerts, Jerry presents jazz improvisation clinics and mallet master classes at colleges and universities in North America and Europe. “College students really dig jazz. They’ve outgrown their high school music of the moment.” When teaching jazz clinics, he says, “I always do a lot of playing to allow the students to see and hear my technique.”

Jerry cautions students about going into music nonchalantly or without completing college. He explains that he has seen too many young drummers attempt to bypass college. “They’re not getting the preparation needed to excel, to become a pro, and compete,” he says.

Having lived in New York City and Los Angeles, the Tachoirs headed to Nashville in 1979, where friends told them there were opportunities for musicians with skills like theirs. “In the good old days people were running from session to session at specific times. Today, that’s not the kind of routine that has made careers for a lot of the session kings in Nashville,” he says.

Now everyone needs to be more flexible because a lot of musicians are recording in home studios. With great microphones, digital equipment, and computers, Jerry says, you can do anything. “I record all my projects in my own studio, and mix it at my leisure.” The space was designed to accommodate his sound, and he says the quality is better than any major studio he has recorded in.

Jerry becomes nostalgic when he talks about the days of vinyl. “It had a story. Now, it’s shrunk down to a CD.” Worse yet, with iTunes and similar services, you typically buy a track, not an album. The sense of ownership that came with a record is gone. Still, he recognizes the need to move on. He’s changed with the times, making technology work for him. “I teach people all over the world via Skype and Facetime. The industry has evolved. It’s not great, it’s not bad, but different.”

What hasn’t changed for Tachoir is his love for the music. At 61, he says, “I still love what I do.”