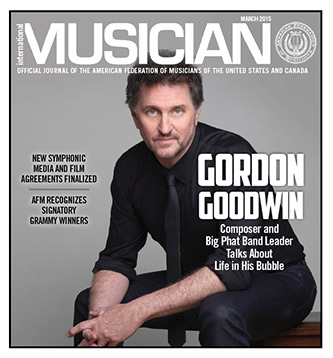

by Rochelle Skolnick, AFM Symphonic Services Division Counsel, Schuchat, Cook & Werner

Under the Bus, On a Pedestal, or Business as Usual?

Fairness and justice are hallmarks of unionism. Unions have fostered the concept of equal pay for equal work: the expectation that the person standing next to you on the assembly line, or sitting next to you on the stage, receives the same rate of pay. So it is uncomfortable, but also important, to examine two ways in which our industry fails to live up to that ideal: “discretionary” individual overscale and compensation for subs and extras.

Ask any savvy elder statesman of the business and he will tell you the practice of individually-negotiated overscale predates the start of his career. But commonplace as it was and still is, such individual overscale exists in a shadow realm, separate from scale wages and collectively-negotiated overscale percentages for titled players. These latter amounts are visible for all to see on the face of the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) and, like compensation for doubling, are tied to the expectation that individuals who hold certain positions bear additional responsibility and should be compensated accordingly.

Discretionary overscale, on the other hand, is generally kept confidential and a musician’s ability to obtain it depends on a range of factors including the musician’s rapport with those holding the purse strings, his or her perceived value to the institution, and negotiation skill. The League of American Orchestras’ Antitrust Policy prohibits managements from sharing with one another specifics of individually negotiated overscale payments (although it does provide for sharing of aggregate data) as a form of collusive price-fixing. Musicians themselves are often reluctant to share specifics for fear of compromising the confidential relationships that yielded the deal. Such secrecy, whether enforced or simply cultural, stands in stark contrast to well-established labor law protections for employees to discuss with one another their terms and conditions of employment—wages in particular—as a necessary predicate to collective action.

At the other extreme from those whose individual bargaining power opens the door to discretionary overscale, are subs and extra musicians who depend entirely (with rare exceptions) on the collectively-negotiated wage scales. Subs and extras have always been indispensable to the American symphony orchestra, but when employers propose cutting or leaving core positions unfilled to save money, the ability to attract and retain first quality subs and extras becomes critical. These musicians have trained in the same conservatories as “regular” players, sit side by side with them, play the same works led by the same conductors, and perform for the same audiences. While they are often (but far from always) compensated at a per-service rate that is intended to approximate the service rate of salaried musicians (and often receive pension), subs and extras have no real job security nor (with rare exceptions) access to the other benefits (e.g., health, disability, and instrument insurance and paid sick leave) that regular musicians enjoy. Under these circumstances, focusing solely on service rate tells only part of the story. Complete parity is illusory so long as these musicians are anything other than regular contracted musicians.

In general, there is nothing unlawful about either individual overscale or a lack of parity for subs and extras. Where a union has been designated as the exclusive bargaining representative of employees (as is the case in all of our AFM-represented orchestras), the employer must deal with the union regarding the employees’ terms and conditions of employment. Because the law recognizes the great potential for mischief and divisiveness when employers bypass the union to deal directly with employees, the employer must have the express permission of the union to do so. In our industry, we have consistently granted such permission, although our contracts do sometimes limit individual bargaining, and in any case, such individually bargained terms may not be less favorable than the collectively bargained ones.

Nor does a union’s duty of fair representation (DFR), taken on when it becomes the exclusive bargaining representative, require it to bargain precisely the same compensation for each and every bargaining unit employee, regardless of facts and circumstances. Whether or not a given CBA specifically includes them in its definition of the bargaining unit, subs and extras perform bargaining unit work and are therefore bargaining unit employees, entitled to fair representation by the union as a legal matter.

The DFR requires only that a union exercise good faith in the performance of its representational duties and not act in a manner that is arbitrary or discriminatory. It does not preclude a union from bargaining different terms and conditions for different groups or classifications of employees, so long as the union acts reasonably in doing so. Nor is a union required by law to afford a contract ratification vote to every musician who may work a single service under an agreement; CBA ratification is an internal union matter and a union may set reasonable parameters when determining eligibility to ratify.

However, “not unlawful” is not always the same as “wise.” Adverse consequences abound. All too often in bargaining an employer walls off substantial funds for discretionary overscale, separating them from the “pie” available for across-the-board wage increases, but considering overscale a musician salary expense all the same. As discretionary overscale payments become more substantial and commonplace throughout a bargaining unit, bargaining for scale wages that takes place between the employer and the union remains meaningful only to the few who cannot or will not negotiate their own special deal. When subs and extras are essential (as they always are) to musical excellence, an employer (and bargaining team) that fails to safeguard their compensation does so at its own peril.

It seems to me that our industry has not fully reconciled the artistic individualism that makes for fine, exciting performances with the collective consciousness that makes for well-organized, well-compensated orchestras. Employers who see the union and musicians’ collective as the adversary are only too happy to exploit that tension. I am a pragmatist: I harbor no illusion that the symphony orchestra will ever become a Utopian ideal of fairness, doing away altogether with compensation irregularities. But pragmatism also requires that we regularly take stock of the sources of and threats to our bargaining power. Where it is within our control as musicians, we must ensure that industry practices with such destructive potential, no matter how deeply embedded in our history, are not allowed to subsume the collective strength