There’s something magical about New Orleans and its connection to music and musicians. Through the good times and the bad times the music plays on and the city retains its charm. Musician elders pass down their traditions to the next generation, much like their parents and grandparents did before them.

There’s something magical about New Orleans and its connection to music and musicians. Through the good times and the bad times the music plays on and the city retains its charm. Musician elders pass down their traditions to the next generation, much like their parents and grandparents did before them.

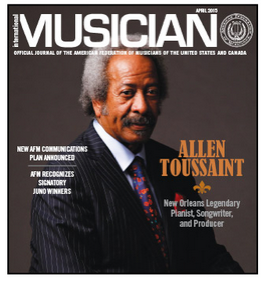

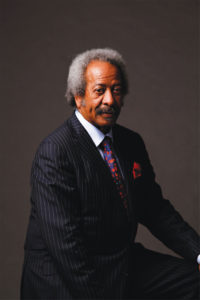

Pianist, producer, and songwriter Allen Toussaint, longtime member of Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA), is one such musician. “I love everything about New Orleans,” he says. “I was born and raised here and I will always be here. I still walk around New Orleans and enjoy what I see; I enjoy what I feel. It’s just a charming place to be and I’m glad I haven’t outgrown the charm.”

The street musicians still go in front of Jackson Square and check out a bench, pull out their horns, and start playing. It’s not traveling musicians; its musicians that came up here, just like Louie Armstrong did, and a whole lot of other greats from the past,” he says. “And that music that you thought you would like to hear if you got to New Orleans? When you get here, you can really hear it.”

Studying Up and Signing Up

As a child, Toussaint, was inspired by the music all around him. He began teaching himself to play the family piano at about age six. When he first showed interest and ability his mom enrolled him in a classic junior school of music, but she had to give up on the idea after six or seven lessons. “The boogie woogie already had me,” he laughs.

Toussaint knew from a young age that he wanted to have a career in music. He taught himself to play whatever he heard, both on the streets and in recordings. Among his early influences were Local 174-496 members Fats Domino and producer/arranger Dave Bartholomew, Ray Charles, and boogie woogie players like Albert Ammons and Pinetop Perkins.

However, his biggest influence was Professor Longhair, or simply Fess. Toussaint was drawn to his music. “So many things were like so many other things, but Professor Longhair was totally unique,” explains Toussaint. “He played with such demand—his voice and his whole vernacular. Plus, there was a strong element of New Orleans. He mixed with junka and he had rumbas in his left hand. It was really hip to bring those worlds together. Every new record he came out with I got it and studied it. It was very, very important.”

Toussaint took learning music very seriously. He wanted to be ready when it came his time to play. To prepare, he learned all of the popular songs of the day and he joined the AFM. “I joined the musicians union when I was about 15 because I didn’t want anything to be in the way of me performing anywhere I’d ever be called,” he says.

Subbing for Huey

Toussaint’s first big break came when he was just 17. “Earl King had a performance in Pritchard, Alabama, and Huey Smith had taken ill and couldn’t make it,” recalls Toussaint. King’s saxophonist knew Toussaint “as a young pianist around town who knew all the songs of the day on the radio” and they called him to sub.

Toussaint’s first big break came when he was just 17. “Earl King had a performance in Pritchard, Alabama, and Huey Smith had taken ill and couldn’t make it,” recalls Toussaint. King’s saxophonist knew Toussaint “as a young pianist around town who knew all the songs of the day on the radio” and they called him to sub.

He met the band at the Dew Drop Inn and they went straight to Pritchard for the gig, no rehearsal. “I knew Earl King’s repertoire very well and I had a very good time,” says Toussaint. “That was my rite of passage from the teenage world to the adult world, even though I was too young to be in that kind of club.”

“That introduced me to the Dew Drop set,” continues Toussaint, explaining that the Dew Drop Inn was New Orlean’s answer to the Cotton Club. It was where all the musicians congregated before they went out to perform. From there, other gigs happened, and a couple years later he replaced Smith in the same band, which was now backing the duet Shirley and Lee. “That was my first time touring,” he says.

Toussaint recalls the special feeling of camaraderie among New Orleans musicians. “It wasn’t a competition; we shared licks with each other; we shared ideas. There was what we called ‘turn-backs’ in music. You might see someone you hadn’t seen in awhile and you would say, ‘Hey, share a turn-back with me.’ We were very glad to know that others were on the scene and what they were doing.”

“I think it’s still pretty much like that,” he explains. “We certainly feel a heritage within each of us. New Orleans has a certain pace and all, an innate thing that is felt without saying words. I’ve always felt that and I still feel that, even with very young musicians.”

Songs from Behind the Scenes

Toussaint’s first recording was for RCA in 1958, and featured his composition “Java,” later a hit for trumpeter Al Hirt. Toussaint most enjoyed the behind the scenes work of songwriting, arranging, and producing. By the early ’60s he was session supervisor for Minit and Instant Records, writing and producing singles for local artists.

But just as his career started to pick up steam, he was drafted into the military for two years. At the time, he worried it would affect his blossoming career. “I thought everyone who was doing what I do was way around the track because they’d been on the case and I’d been on hiatus,” he says. “That was the only time in my life that I tried to write a hit song. I wrote the song ‘Ride Your Pony’ because I thought all the other horses were all the way around the track.”

In the end, his talents for producing and songwriting allowed him to resume his career pretty quickly. “Ride Your Pony” became a hit for Lee Dorsey in 1965, and Toussaint has since racked up hits for artists ranging in genre from pop to R&B to country.

Toussaint partnered with promoter Marshall Sehorn and launched Sea-Saint recording studio. There he produced and wrote for artists like Lee Dorsey, the Meters, Dr. John, and others who drew heavily on New Orleans traditions.

Over the years, Toussaint’s timeless songs have been recorded and rerecorded. For example, his tune “A Certain Girl” written for and released by Ernie K-Doe (1961), was later covered by the Yardbirds (1964), as well as Warren Zevon (1980). “Fortune Teller,” first recorded by Benny Spellman (1962), was later covered by The Rolling Stones (1966), The Who (1970), The Hollies (1972), and Robert Plant and Alison Krauss (2007). Songs like “Get Out of My Life, Woman” and “Play Something Sweet (Backyard Blues)” have been performance favorites for bands from around the globe.

As a producer and songwriter Toussaint is particularly skilled at bringing out the best in whatever artist he works with. “My habit has always been to write for particular artists. I listen to them a bit to hear what I think could be highlights in their voice, how they feel about themselves, how expressive they would like to be. It’s for that particular person, as if I was making a gown or suit,” he explains.

Among Toussaint’s favorite covers of his songs are Herb Alpert’s “Whipped Cream” (1965), Al Hirt’s “Java” (1964), and Glen Campbell’s “Southern Nights” (1977). “I do love all the versions of every song of mine I ever heard, whether they are removed from where I may have had them originally, or if they are almost verbatim,” he says. “I just feel so grateful that someone cared enough about a song that I wrote to take it to their own heart, live with it, learn it, and then have it come out of them. That’s a wonderful miracle collaboration to me.”

“I never thought of myself as a stage performer,” continues Toussaint. “I’ve always thought of myself as the one behind the scenes. If there was a band, I would be the one to listen to the recordings of songs we are going to do and arrange the music.”

Over the years Toussaint has been involved in numerous hometown productions, performances, and projects, serving as arranger and musical director. In 1996, he launched NYNO Records with New York radio syndicator Joshua Feigenbaum to record and distribute the roots and R&B music of New Orleans and “paint a musical portrait of the city.”

Emerging from the Storm

Fifty years into his career, Hurricane Katrina abruptly changed everything for Toussaint. He rode out the storm at the French Quarter’s Crown Hotel and then evacuated the city four days later, having lost his home, studio, and all of his possessions except what he’d brought with him—the clothes on his back and his irreplaceable personally recorded videos. On Feingenbaum’s suggestion Toussaint fled to New York City. He had no real plan.

Fifty years into his career, Hurricane Katrina abruptly changed everything for Toussaint. He rode out the storm at the French Quarter’s Crown Hotel and then evacuated the city four days later, having lost his home, studio, and all of his possessions except what he’d brought with him—the clothes on his back and his irreplaceable personally recorded videos. On Feingenbaum’s suggestion Toussaint fled to New York City. He had no real plan.

“I did several benefit concerts to survivors of our area and that exposed me to more performances than I had ever done in my life on my own,” he says. “I must say that it’s been quite rewarding, but that’s not how my life was going before Katrina.”

Despite having to live outside the city he loved for two years, and losing his home, today Toussaint focuses on the positive outcome. “I perform quite a bit now in comparison with before Katrina, and I must say it’s been quite gratifying,” he says. “It’s really wonderful because all my time was spent in the studio, and though I was very comfortable there, the final analysis is that we are trying to reach people when we record, write, and arrange. When we are on stage, there the people are, right there. It feels so much more like music was intended to be. It gives you such a more human aspect to the whole process.”

Throughout his career, Toussaint says his decision to join the union has served him well. “There are some places that the pay and all was very secure because the union was definitely on the case,” he says. “One of the best unions in the world is Local 802 (New York City). They really take care of business and see that things are intact and benefiting musicians as much as possible.”

After 60 years in the industry, Toussaint thoughtfully looks back at how the business has changed in recent years due to digital technology, and how those changes impact the culture of music in the Big Easy. “New Orleans is affected by musical changes, as well. Nowadays you can turn on one button and the whole world hears the same thing, at the same time,” he says. “New Orleans has held onto its own traditions as well as it could in the midst of so much technology. Even though they can hear the world playing back at them on television, radio, and the Internet, musicians here are playing the New Orleans traditional music that they got from someone a bit older than them, in New Orleans.”

“They hold past members who have gone on as deities, which is very important,” he continues. “It preserves the richness of the music and the intent of it in the earlier days. You could not know that the early music existed unless you take it to your heart and live in an environment where others are playing it just