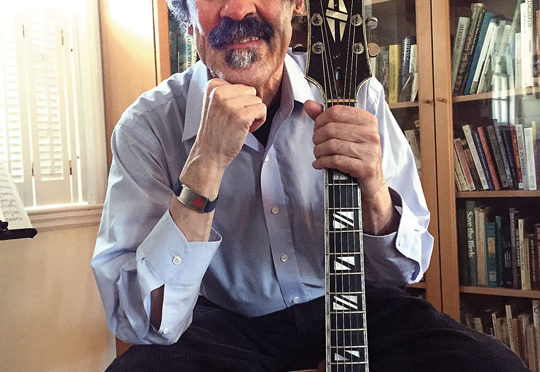

In 2011 bassist Rick Robinson of Local 5 (Detroit, MI) set out on a mission to bring classical music to the masses.

Just after the 2010-2011 Detroit Symphony Orchestra strike, and during an especially difficult time in his life (including the death of his father), longtime DSO bassist Rick Robinson of Local 5 (Detroit, MI) says it seemed like the time to take a risk. “You’ve got one life to live. I decided I should take it all the way.”

He left the orchestra to work full-time with his own production company, CutTime Productions. Robinson, a Kresge fellowship winning composer says he’s focused on “demystifying the huge classical tradition for broader humanity.” He aims to change the way classical music is presented for the lay audience, utilizing nontraditional settings—casual venues, cafés, clubs, restaurants, classrooms, and festivals.

The ensembles include CutTime Players (a mixed octet), which performs full and abridged symphonic masterpieces and CutTime Simfonica (with strings and percussion), featuring abridged openings of symphonies and Robinson’s own compositions, blending urban pop with neo-classicism. He calls it “an on-ramp to Schubert, Mozart, and Brahms, the music I love so much.”

What makes these programs unique is that Robinson and his musicians are willing to play in noise—in bars, clubs, and restaurants. “That’s a deal breaker for most symphony musicians,” says Robinson. “We play lively music to show that aspects of dance are in classical music. We pass out toy percussion instruments to the audience and ask them to join in. We talk about the development and the significance of instrumental music.” And then there are the burning questions, Robinson says, like, “Why is it called classical in the first place?” and “Why do you guys wear tails?”

Classical music can be adaptive, Robinson insists. In its reconstituted form, it can be spiritual and spontaneous all at once. Instead of centering on the art in the concert sanctuary, CutTime centers on the audience. “Once we focus on the audience, it doesn’t matter how precisely we play. The excellence comes from whether we can draw them into the music,” he says.

In the 25 to 40-year-old crowd he has a particularly captive audience. “In the orchestra world we learn to serve knowledgeable audiences within our arts bubble, which I realized was kind of a church-like experience. But I started thinking, what about everybody else? How are they being served by classical music? Some people hear better on their feet or with a drink in their hand, eating food, or with friends and family.”

“Jazzing up Mozart can make it more relevant,” he says. “The industry has always referred to this as ‘dumbing down.’ But we need to get beyond dumbing down to smarten up for a new audience.”

Robinson grew up in Highland Park, Michigan, in a fourth-generation musical family. His mother played the piano and sang. When he was 10 years old, his older sister and brother took him to a chamber orchestra rehearsal led by Joseph Striplin, one of the first black musicians to play in the Detroit Symphony. “When I first heard Brandenburg No. 3,” Robinson says, “I cried. That’s when I decided to take up cello.”

By eighth grade, he had changed to double bass. After Interlochen Arts Academy, Robinson went to the Cleveland Institute of Music and then New England Conservatory to study with Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Local 9-535 (Boston, MA) member Larry Wolfe. In 1987 Robinson won the Haddonfield (NJ) Symphony Concerto Competition playing Bottesini’s Concerto No. 2.

Following school, Robinson became principal bass of the Portland Symphony Orchestra in Maine and assistant principal of the Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra, led by John Williams of Locals 47 (Los Angeles, CA) and 9-535.

In 1989, Robinson returned to his hometown to become the second African-American to hold a chair in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. That’s when Robinson began adapting solo works from other instruments.

“The AFM is a major partner of DSO musicians, particularly through negotiation times, and especially during the six-month strike of 2010-2011,” he says. “The Detroit Federation of Musicians has shown it’s flexible to the changing times we’re all facing, with audience decline and reprioritization of foundation grants. The union—particularly the collective bargaining agreement—of major orchestra musicians is critical to maintaining benefits and working conditions.”

Robinson hopes to train and hire hundreds of resilient musicians in what he calls the new classical tradition. He says, “Bringing this fine art into a commercial ecosystem will bring balance to the force of classical music and change the conversation.” In the meantime, Robinson says, he’s having fun—a lot of fun!