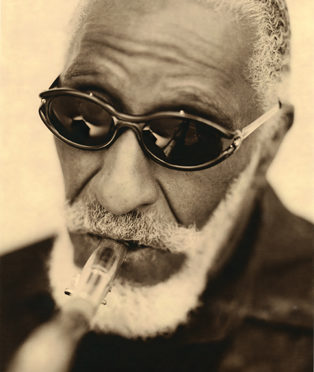

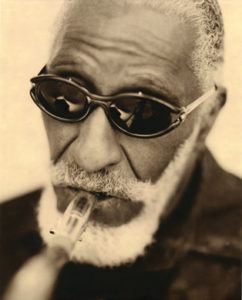

JoAnn Falletta of Local 125 (Norfolk, VA), music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic and the Virginia Symphony, and legendary saxophonist Wayne Shorter will be inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in October.

A recipient of many of the world’s top conducting awards, Falletta’s recordings have also garnered two Grammy awards and multiple Grammy nominations. She is frequently invited to guest conduct nationally and abroad, with performances in Montreal, Spain, and Finland, as well as recordings with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the London Symphony.

A recipient of many of the world’s top conducting awards, Falletta’s recordings have also garnered two Grammy awards and multiple Grammy nominations. She is frequently invited to guest conduct nationally and abroad, with performances in Montreal, Spain, and Finland, as well as recordings with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the London Symphony.

Jazz saxophonist Shorter of Local 802 (New York) is equally known for his talent as a composer, with many of his pieces are considered jazz standards. He has played with every major jazz artist and maestro, most notably Miles Davis (along with Local 802 members Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter, and Tony Williams) in the classic Second Great Quintet. In the 1970s, he cofounded the influential jazz fusion band, Weather Report.