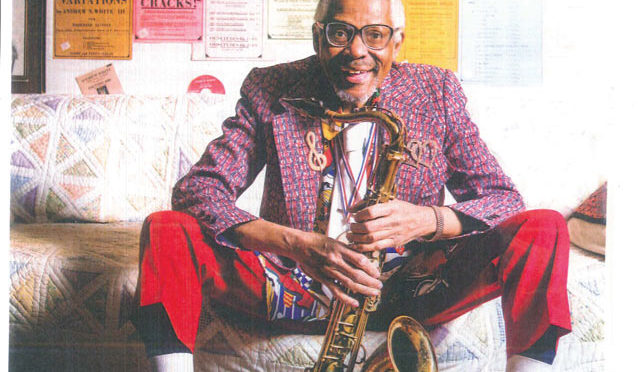

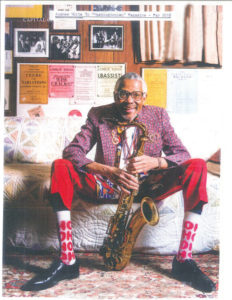

Iconoclastic musician Andrew White of Local 161-710 (Washington, DC) has successfully run a music publishing business for 45 years, which includes an exhaustive collection of John Coltrane solos.

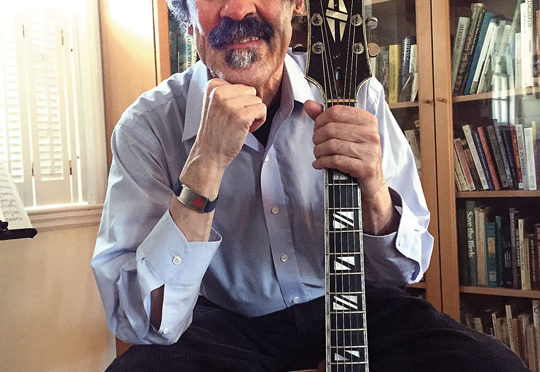

Andrew White is a quintessential artist. A sax player, classically trained oboist, composer, and arranger, a wildly eclectic and spirited genius who has transcribed 840 of John Coltrane’s free-flight solos.

“From the first time I heard Mr. Coltrane, at the age of 14, I thought he was the most significant linguistic contributor to the language of jazz—in the history of jazz. I started transcribing his music because I wanted to see what the music looked like,” White says.

It was only when he turned 70, that White of Locals 161-710 (Washington, DC) and 802 (New York City) started using the term musicologist. He is unaffected and laughs easily. He’s a virtuoso who has mastered many instruments in a range of styles, but who has learned not to take himself too seriously.

He’s transcribed sax solos by Sonny Rollins of Local 802 (New York City), Charlie Parker, Jackie McLean, Paul Desmond, Billy Mitchell, and Stan Getz, plus trumpet solos by Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. White says, “I wanted to satisfy my curiosity about the things I could hear, write them down so I could see them and connect them visually.”

At Howard University, in Washington, DC, White was part of the renowned JFK Quintet. The group played regularly at the legendary Bohemian Caverns. During intermission, White would slip around the corner to Abart’s Internationale to hear Coltrane play.

One night, Eric Dolphy was in the audience. He asked White if he could borrow his horn, and White says, “I was sitting next to Walter Booker, our bassist, and he was laughing hysterically at what Eric was playing. ‘He said, Andrew I’ll never give you a hard time again for your alto sound after hearing that man play your horn. This guy’s playing your stuff.’”

The comparison between the two is now legendary, and White says, “I’ve recorded his tune, ‘Miss Ann,’ twice and people mention the similarities.” White would eventually transcribe 11 of Dolphy’s demanding solos.

In 1963, White went off to Tanglewood to study oboe, and the following year entered the Paris Conservatory on a John Hay Whitney Foundation Fellowship. In early 1965, at 21, White played at the Blue Note Paris, sitting in for Ornette Coleman. “So much of the music business is happenstance,” he says. “I was at the right place at the right time.”

After Paris and another two years at the Center for Creative and Performing Arts at the State University of Buffalo, he joined the orchestra pit of New York City’s American Ballet Theatre in 1968. By then, he was a successful session jazz player and sideman, playing with drummer bandleaders Elvin Jones and Beaver Harris, and recording with Coltrane’s pianist McCoy Tyner. He eventually made a name for himself as a funk bass player with Stevie Wonder of Local 5 (Detroit, MI) for a couple of years—while simultaneously playing oboe for the American Ballet.

White was playing bass with the 5th Dimension in the early 1970s when Joe Zawinul of Weather Report saw him on TV. He and Wayne Shorter of Local 802 knew White could help their band create the funk sound they needed to extend their fan base. In the slicked-up album Sweetnighter, White contributed a distinctive electric bass line, and even played English horn on a couple of tracks.

A descriptor frequently applied to White is “iconoclastic.” He has shared the stage with some of the greatest jazz players in the world and is a deft interpreter of Coltrane, but it was his foray into popular R&B and funk as an electric bassist that ultimately provided the resources he needed to become an independent artist and music publisher.

Since 1971, White has recorded under his independent label, Andrew’s Music, which has an inventory of nearly 3,000 products: vinyl records, CDs, books, his own compositions—nearly 1,000—almost 2,000 transcriptions, and an 840-page autobiography. His catalog includes his series of transcriptions, The Works of John Coltrane, Vols. 1-16: 840 transcriptions of John Coltrane’s Improvisations and the semi-autobiographical Trane ‘n Me, which is a scholarly exposition on the music of Coltrane.

White says he has too many different artistic interests for one commercial label. “Blue Note Records would not record me as an oboe player playing Mozart. Motown would not record me playing as an iconoclastic jazz saxophonist, and Columbia would not take me on as a funk rock ‘n’ roll bass player,” White says. Under Andrew’s Music, he’s been able to do it all.

His own compositions are broad, steeped in eclectic influences, including classical. In 2006, he received the Gold Medal of the French Society of Arts, Sciences, and Letters in Paris, the only American that year to have been presented the honor.

White joined the union in 1958 and jokes that he could go anywhere, play any club, bar mitzvah, or wedding, because his dues have been paid up since 1958.

“As artists, the best thing we ever did was create a union,” says White. With a number of his recording contracts, he has had to invoke the clause regarding reuse. Though there were a lot of opportunities for mishaps, he says that because he had union contracts, he knew to read the fine print. With AFM contracts, “when doing TV, musicians are working for the studio or network and cannot be undercut.” White stresses, “The AFM is a professional organization. Beyond the benefits and the pension fund, it protects musicians on a fundamental level, on stage and in the studio.”

White turns 75 in September and has already begun marking the occasion with what he calls 75th Anniversary Festival Concerts. He started with two shows this spring—one in April at D.C.’s Blues Alley and one in May at the Jazz Gallery in New York City.