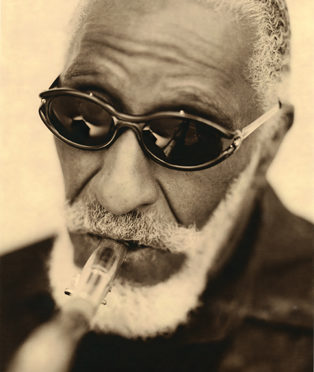

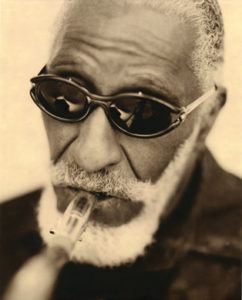

The year was 1930 and Harlem was a Mecca of jazz. Duke Ellington and his orchestra were coming to the end of their residency at the Cotton Club at Lenox and West 142nd, tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins was experimenting with improvisation that would later influence modern forms of jazz, and Fats Waller had composed “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose” just the year before. This was the environment into which prolific tenor sax player Theodore Walter “Sonny” Rollins was born. “Harlem was the black center of culture in the US in those years and I benefited by being close to a lot of great musicians and leaders in the black community,” says Rollins, 78, of Local 802 (New York City). “It afforded me a great education—I was very fortunate to have grown up in this ambiance.”

Rollins’ first stab at music came when his mom signed him up for lessons on the piano. Despite growing up in the birthplace of the Harlem Stride (a style of improvisational jazz piano) mastering the ivories was not written in the stars for Rollins. He preferred playing stickball out in the streets with his contemporaries.

Even though the piano wasn’t the instrument for Rollins, he was fascinated by the rollicking rhythms of Fats Waller and other Harlem musicians he heard on the radio. “He influenced me very much,” says Rollins of fellow Harlemite, Waller. “His music was such a mood lifter; he made sunlight shine every place just by listening to him.”

By the time Rollins was seven, it was pretty clear he had an intense desire to give the saxophone a try. Both his uncle and a family friend played the instrument and one of his idols, Louis Jordan, played the alto sax in a club next to Rollins’ elementary school. Every day Rollins would admire photographs of Jordan plastered to the outside of the club, featuring the musician in a dapper suit and bow tie, holding the shiny horn.

“I don’t want to sound braggadocio, but I always did have this feeling I was destined to be a good musician,” says Rollins.

Once he saw the saxophone in person, he was hooked. “I remember a family friend showing me his saxophone that he kept under his bed,” says Rollins. “It was so beautiful looking, gold and gleaming against the velvet case, oh boy, I was just wide-eyed.”

For 25 cents a lesson, Rollins’ mom enrolled him in the New York Academy of Music. Although Rollins took lessons, he is largely self-taught. He practiced relentlessly and often got lost in his music. Rollins remembers his mom often having to call him several times to come to dinner.

A few years later, Rollins moved to upper Harlem on Sugar Hill where a community of New York’s black elite lived. It was around this time that Rollins’ career as a saxophone player took off. Now, living even closer to music icons Duke Ellington and Coleman Hawkins, Rollins’ reputation as an up and coming sax whiz, began to swell.

After leading a high school group consisting of Jackie McLean, Kenny Drew, and Art Taylor, talk around Harlem provided Rollins opportunities to play with Thelonious Monk and record with Fats Navarro, Miles Davis, and Bud Powell when he was 18-years-old. “I began playing with some of the older musicians and they sort of broke me in,” says Rollins. “I began getting recommended by people and then I met up with Babs Gonzalez who gave me my first recording date in the late ’40s.”

Rollins joined the AFM around the time of these first recordings. “I believe workers need the protection of a union,” says Rollins. “I’m a big union man and I’m proud of it.”

By the time Rollins was 20 years old, he had played many clubs around Harlem with Davis, Charlie Parker, Monk, and Powell.

By the mid 1950s, Rollins recorded three songs with Davis that would become jazz standards: “Airegin,” “Doxy,” and “Oleo.” Rollins began to play with the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet and was featured on several recordings as the leader of the group. His critically acclaimed album Saxophone Colossus, released in 1956, gave Rollins legendary status as an innovator in the area of thematic improvisation. The popular “St. Thomas” track was based upon a traditional calypso song his mother, a native of the Virgin Islands, sang to him as a child.

The excessive praise Rollins received from the album, along with comparisons to other influential players like Charlie Parker, made Rollins uncomfortable. He retreated from public life for three years in what would be the first of several sabbaticals from music.

“I was getting a little bit of a claim in the jazz community and I felt I wasn’t quite up to my claim because I knew there were musical things I wanted to work on,” says Rollins of his leave from the music scene. What is known to many fans as the “bridge period,” Rollins spent practicing his sax on the Williamsburg Bridge, close to his home on the Lower East Side. Once a club headliner, Rollins was practicing in solitude alongside rushing cars, above the East River.

“I learned people have to listen to their inner selves, they can’t do things because they are expected to, or because everyone else is doing it,” says Rollins. “I was going against all conventional wisdom at the time. When I came back, critics said, ‘Gee Sonny, you don’tsound any different since you went up there.’ That may be true, but it gave me an inner strength—that was the big lesson that happened as a result of the bridge.”

When Rollins re-emerged in the music scene in 1962, he released a recording aptly named, The Bridge. For the next several years, Rollins was known for his stream-of-consciousness solo playing and his ability to deftly rework hackneyed and old melodies, making them fresh and his own.

Once again, in the late ’60s, Rollins decided to put his performance life on hold, and studied Eastern philosophy and religion in Japan and India. “I was on a quest to find out about life and its purpose,” says Rollins. “I was always a deep thinker, even as a child.”

Although Rollins doesn’t equate that particular sabbatical with a change in the style of music he plays, he does consider himself an introspective musician. Rollins has a favorite outdoor spot off of the Palisades Parkway, overlooking the Hudson River where he used to play after a night of club gigs in New York. “Just being alone with yourself and your music, that’s a very consciousness-raising thing to do,” says Rollins. “I always like to play in the open under the elements with the feeling of being closer to nature—that’s my heaven on earth.”

Rollins’ nephew, trombonist Clifton Anderson of Local 802, runs the label that they co-own, Doxy Records, and recognizes the spirituality his uncle possesses. “He’s always been that way,” says Anderson. “He always studies to further himself and he’s still in that process today. He leads the way for other musicians to see that the more you know about yourself, the better you are able to assimilate and create what it is you’ve absorbed, and to create something fresh with your music.”

Continuing to seek growth in his music, Rollins still tours with his band, which includes nephew Anderson. Rollins says the discomforts and inconveniences of traveling are all worth it in the end. “I can learn more in one concert than I can in months and months of practicing,” says Rollins. “Nothing can match the thrill of a live performance.”

After releasing live album Road Shows Volume One last year, Rollins is looking to record another album in 2009 with some compositions he’s put together. Mostly, he just feels blessed for his opportunities. “Life is not just one easy ride—there were a lot of horror times,” says Rollins. “Being a musician is not the easiest life in the world but I always knew I wanted to be one. I still practice every day and I am still searching to make a better musical statement. I feel I haven’t really gotten my best work out yet and I’m just so happy to be involved in the thing I’ve loved all my life.”