by Ginny Bales, Member of Local 400 (Hartford-New Haven, CT)

The remarkable career of Local 802 (New York City) and 47 (Los Angeles, CA) member Donn Trenner is highlighted in the book Leave It to Me: My Life in Music.

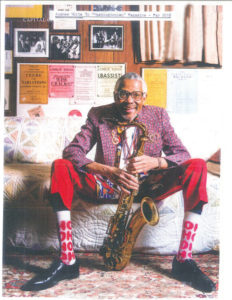

It would be remarkable enough to have played with jazz legends like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Chet Baker, Anita O’Day, and many others; to have entertained the troops with Bob Hope or led the band for the original Tonight Show; to have served long stints as musical director for Ann-Margret, Nancy Wilson, and Shirley MacLaine; and to have declined doing the same for Frank Sinatra. But can you imagine what it was like to tour with big bands led by Les Brown, Charlie Barnet, or Buddy Morrow?

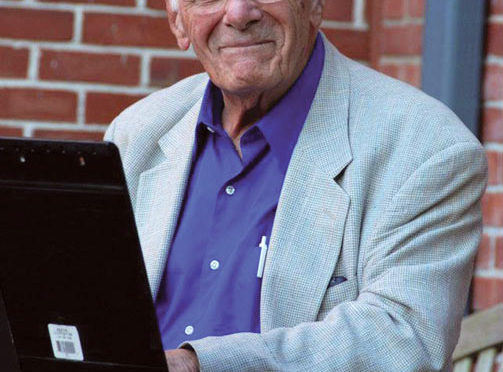

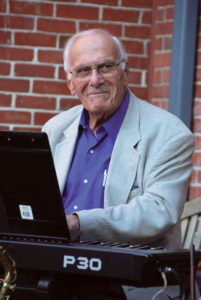

Donn Trenner, a member of Locals 802 (New York City) and 47 (Los Angeles, CA), has done all of these things in his dream career characterized by consistent hard work, unstinting devotion to quality musicianship, and careful attention to making gigs run smoothly on all levels.

The AFM is important to Trenner. “I am a very devoted union member, starting in New Haven when I was 15 years old. I believe the benefits of being a member outweigh anything else,” he says.

Trenner’s life and career began in Connecticut, and we are fortunate that he has returned to this area where he continues to lead the Hartford Jazz Orchestra. Everyone who has ever known or worked with Trenner appreciates his depth of musical experience, gentlemanly charm, and sense of humor.

The book Leave It to Me: My Life in Music (BearManor Media, 2015) by Trenner and Tim Atherton, jazz educator at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and Westfield State University in Massachusetts, tells the tale. It’s filled with gig stories and anecdotes often involving well-known musicians and entertainers.

Those interested in understanding how to write arrangements that work well will find Trenner’s insights invaluable. One section of the book is devoted to his philosophy of orchestration, and the entire book is peppered with observations on arranging, dynamics, instrumental balance, stagecraft, and how to bring the best performance out of other musicians.

At age 90, Trenner continues to be a role model. He connects us to iconic music “scenes” from classic jazz and big bands through international touring, TV, and Las Vegas-style shows. He continues to create beautiful music and also entertain through writing and speaking engagements.

A quote on Trenner’s piano reads: “Don’t just play notes—tell a story.” His key to happiness? “Keep music in your life. Music and laughter are the most important beneficial ingredients in a person’s life.”