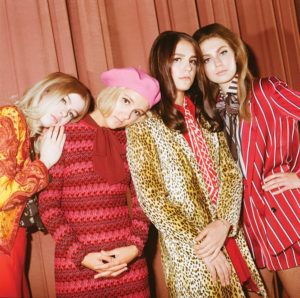

With a career spanning more than 50 years in the recording industry, Local 148-462 (Atlanta, GA) member William Bell received his first Grammy this year in the category Best Americana Album. The honor was fitting for This Is Where I Live, a retrospective album that also marks Bell’s return to Stax Records, where he began his career all those years earlier.

Who knows what would have become of the Memphis native if not for the music emanating from 926 East McLemore Avenue. “Jim [Stewart] and Estelle [Axton] established Stax Records right in the heart of the deprived neighborhood we lived in,” explains Bell. “It kept us out of trouble. We went to the record shop and listened to songs. All the neighborhood kids had an outlet there.”

Who knows what would have become of the Memphis native if not for the music emanating from 926 East McLemore Avenue. “Jim [Stewart] and Estelle [Axton] established Stax Records right in the heart of the deprived neighborhood we lived in,” explains Bell. “It kept us out of trouble. We went to the record shop and listened to songs. All the neighborhood kids had an outlet there.”

Aside from the music they heard hanging out at the record shop, he and friends like David Porter and Isaac Hayes, listened to disc jockey Rufus Thomas who worked for WDIA, the only black radio station at the time. “We heard everything on the radio—country and western, blues, and rhythm and blues. It was just an extension of our lives,” he says. “Music was everywhere—on the radio, in the clubs, and on the street corners.”

William Bell began singing in church, but by age 16 he’d moved on to singing “secular” music and won a Mid-South Talent contest and a trip to Chicago to perform with the Red Saunders Band. Upon return to Memphis, he spent the next five years working with and learning from the Phineas Newborn Orchestra.

Bell wrote his first hit song, “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” in a New York City hotel room during a tour with the band. “We had a night off and it was raining. I’m sitting in the hotel room and missing the girl back home. This song just came to me,” he says. He recorded it with Stax, and even though it was the B side of the record, it ended up being one of the record company’s first hits.

Bell says many of his songs come from a personal place, while others are inspired by the people around him. “I’m a people watcher. I’ll go to a party and sit in the corner and watch the human factor take over. I write about life and things I think people can relate to. Other times I just come up with an idea and construct a song.”

That’s what happened when he wrote “Born Under a Bad Sign” with Booker T. Jones of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA). “It was back in the ’60s when everyone was talking about zodiac signs. I’d finished a bass line, one verse, and a chorus. I was at the studio doing an Albert King session. He didn’t have enough material. I sang it for him and he just fell in love with it, so Booker and I finished

That’s what happened when he wrote “Born Under a Bad Sign” with Booker T. Jones of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA). “It was back in the ’60s when everyone was talking about zodiac signs. I’d finished a bass line, one verse, and a chorus. I was at the studio doing an Albert King session. He didn’t have enough material. I sang it for him and he just fell in love with it, so Booker and I finished

it overnight.”

“We knew that we had something special. But we didn’t know it would become so iconic,” says Bell. One of the most covered blues tunes of all time, Bell wasn’t too keen on recording it for This Is Where I Live when producer John Leventhal of Local 802 (New York City) first suggested it.

Leventhal said he wanted to do a stripped down version, very “back porch-ish.” When Leventhal presented him with a track, the first thing Bell noticed was that the iconic bass line was gone. But after living with it a couple days, he found himself humming along. “The more I listened to it, the more I came to like it,” he says. “We captured it on the first take, so I guess it was meant to be.”

Such open-mindedness has been key to surviving in an industry that has seen tremendous change over Bell’s career. “Technology has changed the playing field. When you record something it’s for the world. You put it on the Internet and everybody hears it at once. You have to really do your homework and create a great product,” he says.

“Years ago, we went into the studio with eight or 10 people and created. That instilled discipline because you had to get it right the first time. Now you can keep going over a part until you get it just like you want it, but it’s a little sterile,” he says. “I’m still from the old school. I like the bodies in the studio so we can feed off each other.”

Bell says the union has helped him tremendously throughout his career. “And they are still fighting,” he says. “Technology has created some new problems for us to get paid. And the new generation thinks it should all be free. But creators have to make a living. We need that body to speak for us. The union kind of levels the playing field a little bit.”

Coming back to the Stax label brought back memories from the early days of Bell’s career. Somewhat of an oasis in the 1960s, Bell recalls that race and gender didn’t enter into the mix at Stax. “We accepted a person for what they could bring to the table in terms of creativity and musicianship,” he says.

Touring with Stax Revues in the early ’60s, the interracial tour was unusual. “We were like 50/50 with the band and the artists,” says Bell. “We caught a lot of flack, but we tore down a lot of barriers because we were a tight-knit organization. If we stopped somewhere to have lunch and they would not accept blacks in the restaurant, none of us went in.”

“We would go to little towns where it was horrible to even stop for gas,” he says. “We set our parameters. Some cities wanted to have two performances for blacks and whites and we insisted on one performance for everybody. They would put the blacks upstairs and whites downstairs, but at least they were all in the same building.”

The 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in Memphis brought the racial unrest from the rest of the country to the forefront. Behind the walls of Stax the music continued under the shadow of grief.

“Sadness hovered over the studio, over the city. We had also just lost Otis Redding [in a plane crash],” Bell recalls. “Outside of the studio the whole atmosphere had changed. It was a bad scene for a while in Memphis. There was burning and looting and practically every building in the neighborhood was touched except for Stax. They had a reverence for us. We would walk the white participants out to their cars and say, ‘Hey guys, they are a part of us.’ They would back off.”

Other things had begun to change at Stax. Longtime distributor Atlantic Records had been sold to Warner Bros. in 1967. When Stewart was unable to reach a distribution deal with Warner Bros., the company refused to return Stax’s master tapes.

When Estelle Axton left in 1969, new vice president Al Bell began rebuilding the catalog, recording 30 singles and 27 albums in eight months. Though it was a period of some success, the atmosphere had changed. “Our tight-knit family became a corporate structure,” recalls William Bell. “Some of the musicians were unhappy. Booker moved to L.A. and I moved to Atlanta.”

“But that’s not why it went under,” he continues. “It was systematically put out of business. It was one of the largest black-owned corporate structures; the year before it filed for bankruptcy it cleared more than $20 million in sales.” The company’s cash flow was affected by its inability to distribute the hit records it was recording, then the minute the company couldn’t pay its debts it was foreclosed upon. The unpaid debt totaled just $1,900 when the bank took everything in December 1975 and escorted the owners out at gunpoint.

“A lot of us artists hung in there until the very last, in lieu of getting our royalties. We wanted Stax to pull out of that downward spiral. Some artists lost homes and cars when it folded. Thank goodness I was in the creative end of it as well, so I could still write and produce for other labels,” says Bell who was so disenchanted with the music industry that he took up acting.

Bell never thought he would record for Stax again. But when Concord Records bought the label in 2004, it began reissuing the classics, as well as creating new records with Stax artists.

Despite the building being torn down in 1989, 926 East McLemore Avenue also saw a rebirth thanks to Bell and other former Stax musicians. “It was a vacant lot with beer bottles thrown about,” he says. “It was heartbreaking after we had spent 14 years, almost 24 hours a day, on that corner.” They just hoped to erect a monument, but once they got the ball rolling through fundraising concerts, community leaders and philanthropists also stepped in and together they formed the Soulsville Foundation.

They unearthed the original blueprints for the building and erected an exact replica, founding the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in 2003. Later they created the Stax Music Academy and Soulsville Charter School, which together cover a whole city block. The current generation of talented Memphis children now has a place to go to learn a craft just as Bell had in his youth.

Bell’s dedication to the next generation doesn’t end there. He is politically active, lobbying for music education through Grammys on the Hill.

He, along with a number of other Memphis artists, including Bobby Rush, Mavis Staples, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Ben Cauley, and Charlie Musselwhite, shared their music legacy through the Take Me to the River film, tour, and an educational curriculum developed through Berklee College of Music. The 2014 documentary (available on Netflix) brought together iconic Memphis musicians, popular young musicians, and students to create music.

“We are working with a lot of organizations promoting and preserving the legacy and teaching the origin of the music. Kids have gotten into sampling so much. We are trying to teach them how to create their own sound,” says Bell, who continues to tour with Take Me to the River. “Teach kids the ground roots of the development of the music, and not only from the ’60s, but all the way back so they can get a good foundation. Once the get a good foundation, they can survive in it.”

Of the proceeds from the film, 75% goes to the Soulsville Foundation and organizations that support musician well-being.

Bell says they are now working on Take Me to the River Part 2 with New Orleans’ musicians. He is also active with the Notes for Notes, which gives kids access to instruments, recording studios, and mentors/educators to teach them about the music business.