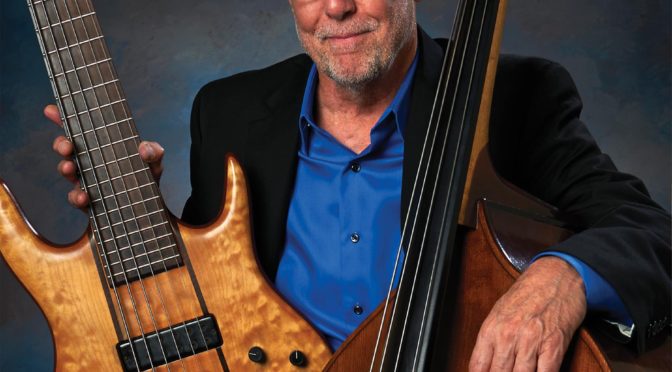

Kristian Bush has been a successful professional union musician since the 1990s, but it’s only recently that the Local 257 (Nashville, TN) member launched his first solo album, Southern Gravity. After spending his most recent 10 years as the silent but creative voice behind the duo Sugarland, the singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist says some people are surprised to hear him sing.

“When I started Sugarland it was pretty clear that my voice was not going to fit on country radio. At the time, the singers signed had rich baritone voices, but now my voice feels like a good fit for current commercial country music. So this first record, my third first record, weirdly enough, is right on time,” says Bush.

Long before Sugarland, Bush had already achieved commercial singing success in the folk rock duo Billy Pilgrim with

Andrew Hyra more than 20 years ago. That’s when he first joined Local 148-462 (Atlanta, GA). “I’m a very proud union member,” he says. “It always feels like there’s another person in the conversation every time I get paid, which I am grateful for because this business is complicated and has changed dramatically since I signed up

in 1994.”

Bush later transferred to Local 257 with Sugarland. “The Nashville union is very thorough on their approach to protecting musicians,” he says, “really making sure everybody gets the most they can get paid out of every session.”

Bush later transferred to Local 257 with Sugarland. “The Nashville union is very thorough on their approach to protecting musicians,” he says, “really making sure everybody gets the most they can get paid out of every session.”

Bush founded Sugarland in 2002 with his friend Kristen Hall. Jennifer Nettles, also a member of Local 257, was the fifth singer to audition for lead vocalist and co-songwriter with the group. “She blew it out of the water,” says Bush.

“The second song we wrote together was ‘Baby Girl,’” he says, recalling their quick success after Nettles joined. As Sugarland’s debut single, the song eventually went to number two on the Billboard Hot Country Singles & Tracks charts, and stayed on the chart for a record-setting 46 weeks. Sugarland became a duo when Hall dropped out after the first album.

Between 2004 and 2012 Sugarland released eight successful albums and racked up dozens of music industry honors, including the 2005 American Music Awards Favorite Breakthrough New Artist, the 2006 ACM award for Top New Duo or Vocal Group, two Academy of Country Music (ACM) awards for Top Vocal Duo and one for Single of the Year, five Country Music Association (CMA) Vocal Duo of the Year awards, four Country Music Television (CMT) Duo Video of the Year awards, and two Grammy awards.

Check out the gear Bush prefers using.

Tragedy Follows Success

Sugarland’s success was suddenly and tragically tempered by pain on August 13, 2011. The stage collapsed above them as they waited underneath to begin a show at the Indiana State Fair. Seven people were killed and 100 others were injured, among them stagehands, security personnel, and fans. Though he and Nettles were uninjured, Bush says the event changed him forever in ways that he hasn’t even totally understood.

Sugarland’s success was suddenly and tragically tempered by pain on August 13, 2011. The stage collapsed above them as they waited underneath to begin a show at the Indiana State Fair. Seven people were killed and 100 others were injured, among them stagehands, security personnel, and fans. Though he and Nettles were uninjured, Bush says the event changed him forever in ways that he hasn’t even totally understood.

“Music should be a safe place, no matter what. I certainly look up now every time I walk on stage,” he says. Some of the stage crew led a charge for better stage safety following the tragedy, which has resulted in new regulations for safer outdoor stage rigging techniques.

In 2012, Nettles decided she wanted to take a break from Sugarland to start a family and make a solo album. When the pair put Sugarland on hold, Bush says an independent career wasn’t something he’d even considered. However, fueled by a particularly emotional time in his life, he suddenly found himself flooded by songs.

Not only was he dealing with the aftermath of the stage collapse, but also the breakup of his 12-year marriage. He didn’t speak publicly about either until earlier this year. Instead, he poured his emotions into songs. “There was a lot of sadness and mourning, but every once in a while an incredibly bright song would pop out. They are like hot air balloons; you just kind of want to hold onto them and see if they lift you up,” he says.

But, with his sudden productivity, came self-doubt. “I usually write about a song a month—12 to 15 a year; suddenly, kind of as soon as we parked the bus off the last tour, I was writing one almost every other day,” he says. “I was a little worried that the songs weren’t any good because they were coming too fast. It was unsettling and it started to make me question what I should do for a living. What if, at this level of success, people aren’t telling me the truth?”

To counter his doubts Bush sought collaborators. “I thought the only way I could figure out an honest answer was to write with the best people I could find. I went all over the world,” he explains. “I went to see Will Jennings in LA, and I said, ‘Teach me how to write for film’; I went to Stockholm and Jøgen Olsen and said, ‘Teach me how to write a pop song’; and I went to Nashville, to Paul Overstreet and Bob DiPiero [of Local 257], and said, ‘Teach me how to write the best country music’; and I went to London to Sacha Scarbeck and James Blunt.” These influences and co-writers can be heard on Southern Gravity.

Right Time for Radio

Bush says that, even when he knew he had the songs, he was still reluctant to take focus away from Sugarland. “Then, I figured out that my voice, Jennifer’s voice, and the band can be on the radio at the same time; it was not going to affect my band for me to have a solo record,” he continues. “I now have two careers. Sugarland is still together; we have a couple records left with our label and it’s going to be super exciting when we get to do it.”

Bush says that, even when he knew he had the songs, he was still reluctant to take focus away from Sugarland. “Then, I figured out that my voice, Jennifer’s voice, and the band can be on the radio at the same time; it was not going to affect my band for me to have a solo record,” he continues. “I now have two careers. Sugarland is still together; we have a couple records left with our label and it’s going to be super exciting when we get to do it.”

The final hurdle was figuring out, from all the songs he’d written and recorded, just what he wanted to sound like. “Thinking about what I sound like can be unsettling at first,” he says. “I wrote 300 songs for this record and recorded them all. The process of that almost felt like discovering my voice.”

Bush co-produced the album with executive producer Byron Gallimore and Tom Tapley, whom he also worked with on Sugarland’s studio albums. “I love producing albums,” says Bush, “but it’s weird to produce your own vocals. You have to emotionally detach yourself. So the hardest part is the speed. I would do full takes, cut them together, and then take it home and listen to it for two or three days.”

In the end, they created an album far removed from the emotional turmoil where it began. Instead, Southern Gravity is hopeful, even joyful. “These songs are like Post-it notes that you might put around your house as inspirational reminders,” says Bush. “I listen to them for that reason sometimes—to remind myself that no matter how hard it gets, you can make things out of the pieces that are smashed.”

Once the songs were complete, it was time to begin his first solo tour. Bush admits that, even as a veteran musician, it felt strange to take the stage as a solo act. “I was so nervous my first show. It was strangely at the [huge] O2 Arena in London and I was opening for Little Big Town and Tim McGraw. I walked out on stage and my heart was practically beating out of my chest. I broke into the first song, and suddenly it was like, ‘Wait a minute, I totally know how to do this!’” he recalls.

Bush recently had the opportunity to look back on his career through a new documentary to air this month called Walk Tall (also the name of one of the tunes on his album). “It’s about Southern Gravity, but it’s also a journey, and what it’s like to make music after terrible things happen,” he says of the film. “As Americans, as people, the idea of never giving up is really important. When you have a passion, a belief, a joy, whatever life throws at you, the only choice you really have is how you deal with it. I’ve started to realize that there’s a resiliency in loving what you do and you go back to it as a way to ground yourself.”

Two tips for upcoming singer songwriters from Kristian Bush:

1) “Don’t give up; don’t judge yourself until about 100 songs because it’s going to suck for a while. They are going to be emotionally very much like your babies; write them as exercises.”

2) “There is so much technology out there to give you rhythms to write against. Whether it’s an app on your phone, a piece of software, or a drum machine, write against a beat. I love the way lyrics bounce against a rhythm.”

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.