As the 78 members of the Boise Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO) sat in their chairs and prepared to start their Hollywood Hits concert on March 30 (during which film clips would be projected above the stage while the orchestra played the accompanying soundtrack) attendees could not help but notice nearly all the musicians were wearing matching blue and white lapel pins. Before the concert started, BPO Principal Clarinetist Carmen Izzo came on stage, asked for the audience’s attention, and read a statement from an open binder in his hands.

“Before we move on to our feature presentation, I bring some news directly from the musicians of the Boise Philharmonic. This past week, our musicians voted overwhelmingly to come together in union and be represented by the American Federation of Musicians,” Izzo said to loud applause. “Our musicians see this as an important step toward a bright future in which we can be heard as professionals. We hope our management accepts these election results and continues to work with us to move our orchestra forward.”

After the performance, BPO musicians met with patrons in the lobby to answer questions about their announcement. Anyone who approached them saw that the matching pins the musicians all wore said, “Hear Us.”

This March 30 announcement was actually the culmination of about six months’ worth of education, training, organizing, and outright legwork on the part of the BPO Organizing Committee—assisted by organizers from the AFM—that brought the newest orchestra into the AFM fold.

“This is a textbook example of how to do everything right from an organizing standpoint,” says Rochelle Skolnick, AFM director of Symphonic Services, assistant to the president, and special counsel.

“It’s a great model to follow,” agrees Michael Manley, director of the AFM Organizing and Education Division, who assisted the Boise musicians. “They really created a movement in Boise.”

Genesis

The BPO is the preeminent, and oldest, classical music organization of Idaho. The orchestra has worked for decades under a so-called “master agreement” with its board of directors, as negotiated by the musicians on the orchestra committee. For at least the past 10 years, however, there has been a growing unease among musicians regarding their treatment by orchestra management; and there have been numerous discussions of unionizing—although those discussions went nowhere.

But then last fall, BPO Orchestra Committee Co-Chair Allison Emerick, understanding some of the unhappy feelings and issues of her colleagues, met Stephen Chong, president of the AFM local nearest to Boise, Local 689 (Eugene, OR), when they both played a summer festival. She took the opportunity to ask him a few questions. “I said, ‘This is a thing that is gaining a kind of hushed momentum among musicians because we are getting more and more agitated with the state of things’ … so I said, ‘How do we go about [unionizing]? Who do I contact?’” Emerick says.

She traded emails with Chong and then emailed numerous officials of the AFM, and “immediately” received a response from Todd Jelen, a negotiator/organizer/educator in the Symphonic Services Division (SSD). “I told him the gist of our history as an orchestra, and what we were upset about,” she says. Some of these grievances included a musician who recently resigned under “not the best circumstances,” upsetting many members. There were also promises of wage increases and travel pay that were verbally agreed upon but then rescinded by management.

Among the various concerns expressed by BPO musicians, the central issue was the lack of a mechanism to enforce their current agreement, according to violinist and organizing committee member Kate Jarvis. “What we were finding was that our master agreement really wasn’t enforceable by the musicians, and that our concerns were not necessarily met all the time,” she says.

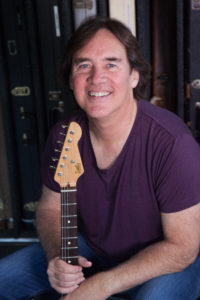

Photo: Musicians of the Boise Philharmonic

Under that agreement, a five-member orchestra committee negotiated with the management on employment issues but, in contrast to the vast majority of AFM agreements, there was no dispute resolution procedure in the contract allowing for a decision by a neutral third party. Any disputes went before the BPO Board of Directors, which had a vested interest in siding with management.

“This was something I felt, honestly, was a long time coming,” says violinist, former orchestra committee member, and organizing committee member Geoff Hill. “I’ve heard a lot of people in the orchestra tell me stories about musicians not being listened to, musicians not being taken seriously. I’ve heard about these stories for years and years and years, and I was seeing these stories before my very eyes because I was on the orchestra committee and had been through negotiations myself. … So it seems like history was just repeating itself again and again.”

After having multiple phone calls with members of the organizing committee, Jelen and Manley flew out to Boise to help them organize.

Learning to Organize

“When you are organizing a group, it’s never about AFM membership. It’s about learning individuals’ issues; it’s about training the committee members on how to be receptive to their colleagues’ issues and needs,” Jelen says. “It’s not so much about telling them what to do, but about bringing them into the thought process and training each individual to make their own choice. Really, it’s about empowering the group to act for itself.”

Jelen and Manley would go out to Boise for three to four days at a time and do intensive training with the committee members—which was unusual. “In new organizing campaigns, it’s typical to have organizers on the ground for weeks on end,” Manley says. “The fact that these musicians did what they did with our focused but limited onsite organizer support, and an AFM local of jurisdiction that is hundreds of miles away, speaks to the passion and dedication they brought in joining together to get what they need.”

Jelen and Manley spent two months training the organizing committee—and also increasing the size of the committee from five to 11 members. One of the first things the committee did was to create a list of every BPO member and rank them by who would be the most to the least receptive to organizing. As they began talking to their orchestra colleagues, they worked their way down that list, starting with those they thought would be the most interested.

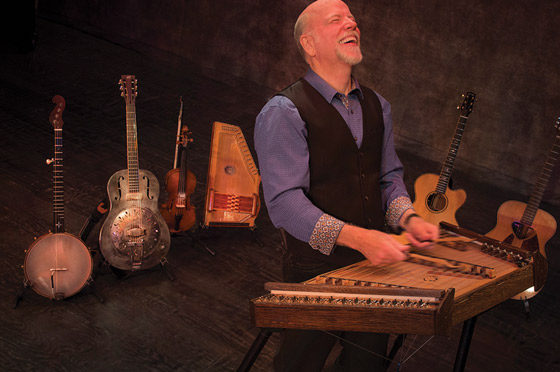

Photo: Musicians of the Boise Philharmonic

“We did a lot of research and development and education and training before we actually talked to people,” Emerick says. “We had really thorough training: general education training, organizing conversation training, how to talk to members individually, what to say, the step-by-step process of asking questions to hear their experiences, that kind of thing.”

“I probably had 20-odd conversations with members of the orchestra and, in my experience, it was extremely positive,” Hill says. “For the overwhelming majority of people, it was empowering.”

Jarvis agrees. “I think most members were open to the idea at the beginning, but there’s definitely some education about it,” she says. “Just getting people to understand what it means and how it might affect them—I think they realized that, yeah, we have some issues, and right now we’re not in a position that we can really effectively do much about those issues and this could be a way for us to move forward with a more meaningful voice in an organization.”

“It was at that point when I realized how organized of an effort this was,” says organizing committee member and associate principal violist Lindsay Bohl. “This is the most organized thing I have ever been a part of; I was really impressed with that right away, just to see that process unfolding.” Those first few meetings—day-long, intensive sessions—included learning the history of labor unions and of the AFM, how to listen to their colleagues’ issues and concerns, how to talk to their colleagues about solving issues, and explaining how the AFM can help the orchestra.

Part of the organizing campaign was to have interested members sign a “showing of interest” card, which states they want to be represented by the AFM local. The committee needed 30% of their colleagues to sign the cards in order for the National Labor Relations Board to conduct a vote on whether to join the union. By the end, the BPO Organizing Committee had gotten 90% of members to sign the cards. “It was an insanely high number,” Jelen says.

“It was extremely validating, but honestly that’s not what it is about,” Hill says. “It’s about knowing that we have the energy and the mindset to do this. It just further drives home the fact that this was something that needed to happen, and that we could have such a high margin of people voting and turning in those cards just really showed, I think, how well it resonated with people around here.”

The vote to merge the BPO Orchestra Committee into Local 689 was even more resounding—with 96% of participating musicians in the BPO voting in favor of joining the AFM.

Moving Forward

The BPO Organizing Committee announced the positive union vote on March 28. The next day, the board and management issued a statement in which they said they were “saddened that the musicians feel alienated and are moving in a new direction without first informing them.” However, negotiations did start immediately—within the board and between the board and the organizing committee. For nearly two weeks, BPO management asked questions of and had discussions with the organizing committee members. On April 15, executives announced that they would recognize their musicians as part of the AFM.

Public reaction to the announcement was largely positive, and the BPO musicians received vast amounts of support during the negotiations, Emerick says. “I think our audience was generally very supportive, and we really heard that in the [March 30] speech, where Carmen announced it to the audience and there is that applause that we weren’t expecting,” she says. “Of course, there were people—and still are people—who are not viewing this very kindly, but we really wanted to deliver the message that everybody involved in this, especially musicians, want to see this orchestra succeed. We love this orchestra, which is our livelihood and as well as our passion, so we don’t want to undermine it. So every single messaging that we put out, we wanted to be clear that this came from a place of protecting the longevity of the orchestra, protecting us as musicians, and having our voices heard in this process.”

Orchestra

management and orchestra committee members have been meeting to discuss the new

collective bargaining agreement, Jarvis says, and the process

is ongoing.

As contract negotiations began, the Boise musicians also worked to create their own local. When they voted to join the AFM, they knew they would become a part of their nearest local geographically: Local 689 (Eugene, OR), 450 miles away. They had initially discussed forming a Boise local as they worked to organize entry into the AFM, but quickly realized it was too complicated to do both at the same time, Bohl says. The plan then became to create their own local in three to five years.

Fairly quickly, however, the Boise musicians realized they could form their own local immediately because there was so much support among the orchestra for the union. “Nobody was against joining the local in Eugene, but everyone asked if we could just do it here,” Bohl says. “We were all kind of tired [after the union vote succeeded] but we said, ‘Let’s do it.’ It was relatively easy to get the 50 petition signatures we needed.”

“Boise has a very local mentality, so everybody was very enthusiastic about it,” Emerick says. “Knowing that if you have a grievance you can just walk downtown and talk to our local, and not have to drive 450 miles to Eugene, was important.” The organizers also decided that, as the only unionized music organization in Boise, they wanted to reach out beyond the orchestra and invite local freelance musicians to join as well, which would only make their organization stronger.

On June 11, just before the 101st AFM Convention, the International Executive Board approved the charter of Local 423 (Boise, ID).

“For me, it feels exciting to have our own local here in Boise that we can take more ownership over. We can create our own bylaws and make our own decisions. I think it will be more empowering to do it that way,” Bohl says.

Lessons Learned

Organizing is, by definition, a grassroots process, says AFM SSD Director Skolnick. It will be doomed to fail if “the union” comes in from outside to impose a vision for the workplace that is inconsistent with what the musicians themselves want and need. “In Boise, as with every truly successful organizing drive, the vision originated with the musicians’ organizing committee,” she says. “The organizing committee then did the hard and time-consuming work of engaging each of their colleagues in discussion about their personal needs and hopes for the future of the Boise Philharmonic. What resulted, with the AFM’s facilitation, was a shared vision that the musicians overwhelmingly identified with and supported.”

So what should musicians looking to organize take away from this success story? “Don’t cut corners; it’s long and arduous work, but it’s worth it in the long run,” Jelen says. “Get more training than you think you need and do the work.”

And that is what the Boise musicians did. “It definitely wasn’t easy; a lot of hours were put into making this happen,” Jarvis says.

“It was a ton of work but it’s probably the most rewarding thing I’ve ever been a part of,” Bohl says. “It was really empowering, and to meet with all our colleagues one-on-one like that was really enlightening.”

Manley calls the Boise organization, “a textbook, traditionally run” organizing campaign, which means it was entirely worker-driven and worker-led. “The union really was the musicians from the start, and the powerful lesson to take away from the Boise campaign is that the union is workers; the union is not local or national AFM officials or staff, it’s all working musicians,” he says.