by Todd Jelen, AFM Symphonic Service Division Negotiator/Organizer/Educator

I was wrapping up a negotiation in Charleston, West Virginia, when I received an email from AFM President Ray Hair, SSD Director Rochelle Skolnick, and Director of Organizing and Education Michael Manley forwarding a request that came through the AFM website. The Boise Philharmonic Orchestra’s (BSO) principal flautist, Allison Emerick, was reaching out to inquire about organizing the musicians of the Boise Phil. We get requests like this each year, and most of them never go past a few phone calls before the effort is abandoned for one reason or another. This time something was different. As I found out in my first conversation with Allison that night as I drove back to Ohio, the musicians in Boise seemed determined to change their situation.

The next question was: Would they commit to doing the work? In the ensuing conversations with the organizing committee, we talked about the issues facing musicians in their workplace. Past agreements had been broken or ignored, and the musicians felt like they had no voice concerning the future of their orchestra. Rochelle, Michael, and I gave them a view of the organizing process and the amount of work that would be needed.

We explained that we could train and guide them, but if this effort was going to be authentic, they would have to do the work. The organizing committee agreed and committed to the rigorous process—and to each other. We held conference calls with the committee at least biweekly (if not weekly) at every stage of the campaign to complete the many tasks ahead of us. We gathered information on the BPO Board of Directors and the community in Boise to build the most complete map of both our opportunities as well as our potential challenges. The Idaho AFL-CIO office was instrumental in helping gather this information. President Joe Maloney, Legislative Director Jason Hudson, Teresa Thomason, and Tracie Roberts, as well as everyone at the IBEW Local 291 deserve commendation for their efforts during this entire process.

Then we determined whom we needed to talk to. Due to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) criteria for our industry, quite a few subs and extras qualified to be organized in addition to contract musicians. This number grew because more musicians met the criteria as the season continued. The list included 125 musicians by the end of the process. We then ranked the list according to the committee members’ experiences and past conversations with each individual. This spreadsheet would become the magnum opus of the campaign. Every detail was tracked and, over time, we were able to make surprisingly accurate predictions about how individuals and factions within the orchestra might side on a given issue. It helped us plan our strategies and it even helped us predict the outcome of the ballot down to one vote.

The next step was to train the organizing committee. Michael and I traveled to Boise for three days of training to get the committee oriented to what they would be facing. The training included the legal rights of workers on the job, the right to organize, how to build transformative rather than transactional relationships, concerted activity, labor history, and, most importantly, the organizing conversation.

The organizing conversation is the model we use to connect with our colleagues. It can, and should, be applied to any and all facets of what we do in the union movement. It is neither an elevator pitch nor a transactional one-sided conversation to extol a list of benefits one might get for joining the AFM in the hopes of “convincing” someone to be involved. Instead, the organizing conversation offers anyone who takes the time to train and practice the opportunity to connect with people in an unparalleled way and guide colleagues through their own thought processes to make their own decisions and to solve their own issues. If done well, and conversing with people interested in change, it will start a movement!

Over the next few months, we systematically held conversations with almost all of the musicians on our list. One by one, we filled out the larger picture of what it would look like to organize in Boise. Once musicians committed to the movement and signed cards, they were brought into the fold through meetings designed to inoculate against a possible anti-union campaign and to help them understand their rights in this process, including their right to participate in concerted activity. To keep musicians updated and engaged, each phase of this schedule occurred monthly, with new people coming into the process through organizing conversations each month. As more and more people became involved, the momentum built until we knew we had enough support to move forward and hold a successful vote.

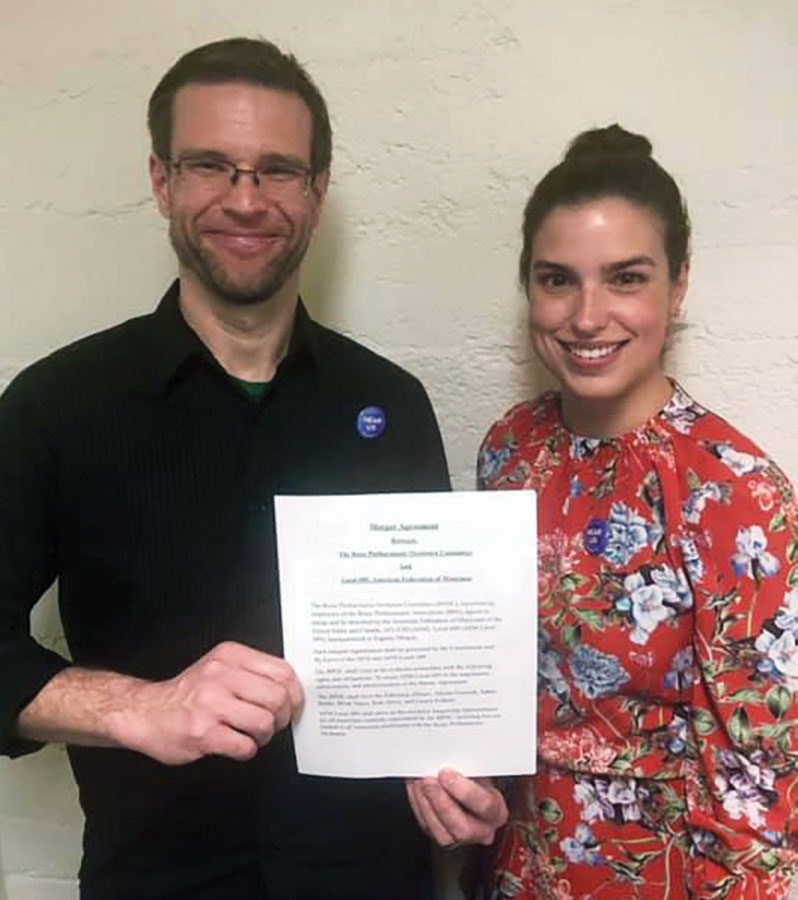

After five months of intensive work, the musicians succeeded in starting a movement in Boise. Based on the extraordinary and diligent work of the BPO Organizing Committee and the commitment and participation of the musicians of the BPO, recognition was quickly achieved. The musicians are unified and focused on the goal of achieving a binding contract with growth as well as working to charter a new AFM local in Boise.

Just prior to the 101st convention of the AFM, the International Executive Board approved the charter of new Local 423 in Boise.

I have been privileged to build a truly transformative experience with both the organizing and orchestra committees of the BPO. We still have some distance to go together as we continue to work towards BPO’s first AFM contract, but I know that the determination of these fine musicians will continue, and the Boise Philharmonic will flourish in the future as the AFM’s newest orchestra.