“It was a really confusing and fantastic thing to watch. There was this huge crowd of people and speeches. And what really hit me was the music—Mahalia Jackson; Marian Anderson; Peter, Paul, and Mary; Bob Dylan [of Local 802 (New York City)]; and Joan Baez. I had never heard folk music before. It was old, but really urgent, and it was connected to something going on in the world.”

Three years later, McCutcheon’s father bought him his first guitar, a Silvertone from Sears. “That began the long downhill slide into professional musicianship,” laughs McCutcheon. The 14-year-old immediately went to the public library and checked out Woody Guthrie Folk Songs, thinking it was a guitar instruction book, and methodically began learning each song. “I was singing ‘Union Made,’ but I had no idea what it was about,” he concedes.

Ironically, McCutcheon’s first gig, just two weeks later, was a Labor Day picnic for the local paper mill union. The neighbor who hired him wasn’t concerned when McCutcheon told him he only knew three songs, but he did require McCutcheon learn one new tune: “Solidarity Forever.”

Through most of the picnic no one seemed to notice the young musician, but when it came time to play that tune, everyone stopped talking, stood up, joined hands, and sang together. “I was flabbergasted!” says McCutcheon. “It was the first crack in the door connecting the principles that I was seeing and the songs I was singing; the song connected real people, in real life, and it moved them to do things.”

“Back then, people were from union families and it was cradle to grave. You just instinctively sided with the guys who were out on strike,” he recalls.

He soon realized the connection between the labor unions and the Civil Rights Movement, his very first inspiration. “When Martin Luther King marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, he was flanked by union guys. At the march on Washington, there were union people all over the dais. It was one great social movement,” says McCutcheon.

From that first union gig, he was hooked, beginning a lifetime of dedication to activism through music. “I wanted that to happen again and I also wanted to have the feeling that I was helpful—doing something that wasn’t just about me,” he says.

“I spent a long time working with different unions,” says McCutcheon. “In this line of work, we [musicians] have it pretty easy. I’m very aware that the hard work gets done by the people I’m coming to sing for. I constantly think about what I can do to help. And that ends up being, not only singing for them, but turning their stories into songs and singing them to other people.”

“Being part of the labor movement for my entire career, and especially being involved with the AFM, helped me keep the sentiment that it’s not just about me,” he says.

A Local for Travelers

One of the founders of “traveling musicians” Local 1000, McCutcheon explains the idea for that local came from musicians at the annual Great Labor Arts Exchange in Silver Spring, Maryland. “We were telling labor war stories of bravery and resolve of the unions we’d worked with and Charlie King said, ‘Wouldn’t it be amazing if we felt that way about our union?’”

“At the time, the AFM essentially didn’t know that people who do our kind of work existed,” McCutcheon explains. “We traveled; we weren’t part of a big ensemble or collective bargaining agreement.”

A group of similar AFM members got together and formed what they called the New Deal Committee to explore the idea. A few years later, at another Great Labor Arts Exchange, someone asked then AFM President Martin Emerson about the possibility of forming their own local. “He didn’t shoot

it down; we started talking and eventually got chartered,” says McCutcheon.

“I remember talking to my buddy John O’Connor, who was the first Local 1000 president,” McCutcheon says. The pair came to a quick realization that they were agitators, not bureaucrats. “That’s when we began learning how to be a local. Local 1000 would never have thrived without the mentorship and help of Local 802.”

“The idea caught on. We were able to open up access to a pension plan through some very creative means via the LS-1 contract,” he says.

McCutcheon was Local 1000 president for 15 years, and now serves on the board of his home local in Atlanta. “Our union has gone through some rough times, but it’s headed in the right direction; I’m really enthusiastic about it,” he says, adding, “We’ve got a lot of myths to break down because the union has changed tremendously in the past 30 years.”

Songs that Move You

McCutcheon has written hundreds of songs, and released 37 solo albums, resulting in seven Grammy nominations. Among other projects were tributes to some of the people who inspired him, among them Woody Guthrie and Joe Hill. In creating the album This Land: Woody Guthrie’s America, Woody’s daughter gave him complete access to Guthrie’s papers, including never finished songs.

A DVD (and CD) project, Joe Hill’s Last Will, is a one-man play written by Local 1000 member Si Kahn. McCutcheon portrays labor songwriter Hill in the final hours of his life.

McCutcheon’s songs are often sparked by events in the news or happenings in his life. “I’m not writing to have a song, or even to finish anything. The more I write, the more I understand that there’s a part of you that you don’t know; it’s wonderful to explore that area.”

“Songs can transport you to another place, help you forget your world or dive you deeper into your world; they can fill you with awe, or rage, or inspiration,” he says. “They move hips and hearts, and sometimes mountains.”

His 38th album, Trolling for Dreams, will be released

February 3. Begun as a collection of earlier songs that never made it onto albums, there’s also some new material. Among the inspirations were a road trip he took with his father who was ascending into Alzheimer’s; his son’s wedding; and a perilous illness last year.

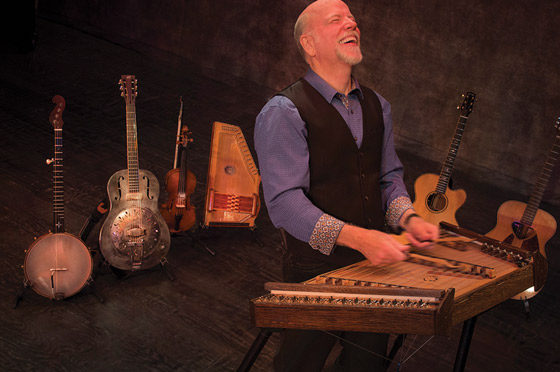

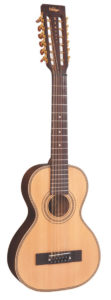

McCutcheon regularly plays more than 15 different instruments. He travels with a hammered dulcimer, 12-string and six-string guitars, banjo, autoharp, and fiddle, plus a piano is waiting at every gig. “I was taught by amazing teachers who never realized they were giving me lessons,” he explains.

While in college, McCutcheon convinced his advisor to let him do an independent study to learn banjo from musicians in the Southern Appalachians. “It was a three-month independent study that I’m still on 45 years later. I went off thinking I was learning how to put my fingers in the right place, and all of a sudden, it was about everything—the context of the music, the community that fosters the music, and the music that sustains the community. I fell in love with the region, the land, the people, the music, and the food.”

Connecting People

At McCutcheon’s shows you will hear a combination of original tunes, labor tunes, traditional songs, classic folk songs, and a healthy dose of storytelling. At first, he had no idea the storytelling would become such a big part of his show.

“Stories are like connective tissue,” he says. “I would tell stories to recreate the environment in which I learned a song, or wrote a song, so the audience could sort of climb inside a little easier.” He soon discovered that his audiences craved the storytelling.

He says “This Land Is Your Land” is always an audience favorite, especially after the contentious election. “It feels like people are yearning for a sense of connection.” The song brings him back to the paper mill workers picnic all those years ago. “It captures an audience in a way that is reflexive, unexpected, and all of a sudden they feel connected to one another.”

“I look for those moments that are unexpected and surprise you with their power,” he says. “I was surprised at 11 years old, hearing those songs, but I didn’t know my life was going to be changed by it.”

Eager to encourage young singer-songwriters, McCutcheon hosts Songwriting Camps at the Highlander Center in east Tennessee—a place that holds special meaning to him. It’s where Martin Luther King heard ‘We Shall Overcome’ for the first time, and it was the initial stop on McCutcheon’s “independent study” program. “I fell in love with this group of people who were activists from all over the Appalachian Mountains, and all of a sudden, the whole region opened up for me in a very real way,” he says.

Largely due to technology he sees a bright future for young folk musicians. “There’s a whole old-time music scene of people that can play rings around the rest of us because they grew up with it,” he says. “The Internet exposes kids to music from around the world and the stuff becomes a mash-up. That’s cool and exciting to see!”

“The dream that fueled me all those years working in a leadership position at Local 1000 is the notion that young musicians will not only find a home within the union, but help to direct it so it morphs to accommodate them. They are full of great ideas, and if we give them the foundation in unionship, we can learn from them and they can learn from us,” he says.