Though multi-instrumentalist Van Bertie of Locals 427-621 (Tampa Bay, FL) and 655 (Miami, FL) was born on a small Caribbean island, his career has brought him all around the world, performing at a wide variety of events.

“My dad was a musician, he played piano and repaired and made pianos and organs,” says Bertie. “I would listen to my father and play along.” Van’s brothers were also musically inclined, and Van first picked up his older brother’s guitar at about age five.

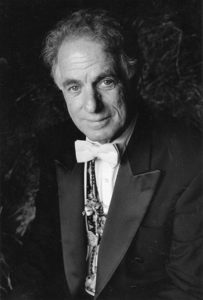

Van Bertie of Locals 427-621 (Tampa Bay, FL) and 655 (Miami, FL) plays guitar, steel drum, and flute.

Growing up on Saint Christopher Island, which is more popularly known as St. Kitts, Bertie thought he could probably earn a living playing music, though he knew it would mean leaving the island. “I started listening to the only radio station on St. Kitts and playing along with all the songs. That’s how I got serious with it,” he says.

At first his four-piece combo traveled around the Caribbean, playing in the Virgin Islands—Saint Croix and Saint Thomas. Then, as a solo artist, in Africa and Canada, he performed mostly Caribbean music, reggae, calypso, plus some R&B, oldies, and top 40 songs. Eventually he landed in New York for a while. “It was cold, and very different as far as culture,” he says.

One day his brother told him: “I’ve got a contract for you to come and play for a cruise ship.” Bertie traveled on cruise ships from island to island for about three years, until he got tired of the lifestyle. He settled down in Florida.

Bertie says he first joined the AFM about 1995, when he was working in Canada. He was encouraged to join by another musician who worked at Disney World. He says the organization has helped him along the way, plus he has a pension plan.

When Bertie first left St. Kitts, he only played guitar. He took up playing the steel drums about 12 years ago due to the popularity of Caribbean music. He also plays some flute. “Right now I am specializing in weddings and corporations, major hotels, and gigs like that,” he says.

He currently also plays in a five-piece reggae band, as well as a blues band. One favorite recurring gig for the reggae band is the Annual Bob Marley Birthday Tribute at the Green Parrot in Key West.