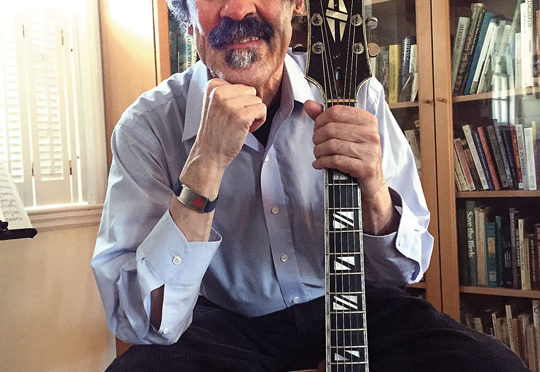

While Randy Kerber may not be a household name, if you’ve watched any movies over the last four decades you’ve likely heard his work. As a studio keyboardist he’s worked on more than 800 motion pictures. His piano solos can be heard on Lincoln, La La Land, and in the opening and closing scenes of Forrest Gump. He’s worked as orchestrator on more than 50 films and most recently as composer for the film Cello.

While Randy Kerber may not be a household name, if you’ve watched any movies over the last four decades you’ve likely heard his work. As a studio keyboardist he’s worked on more than 800 motion pictures. His piano solos can be heard on Lincoln, La La Land, and in the opening and closing scenes of Forrest Gump. He’s worked as orchestrator on more than 50 films and most recently as composer for the film Cello.

Kerber first discovered the world of film music through Ted Nash who he met in Sequoia Junior High School band. Ted’s father, Dick Nash, was a first call trombonist in the studios. “I would go over to the Nash’s house and Dick would be talking about sessions with John Williams, Henry Mancini; it was really a great environment to learn about studio work and what’s behind the music for motion pictures.”

“Dick invited Ted and I to a session for the show Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman,” recalls Kerber. “I sat behind Artie Kane; it was just amazing. He had his legs crossed and kind of faced us, almost sidesaddle on the bench, barely looking at the music. He would talk to me and play when he needed to play. It was this incredible multi-tasking thing.”

In high school Kerber played in jazz band and began writing music. He was selected to perform with the Monterey All-Star Jazz Band as a junior and senior. After graduating, Kerber joined the AFM in 1976. Dick Nash and all of the musicians he’d met at the studios were AFM members. “It was understood that this is what you do,” he says, adding that it wasn’t until much later that he realized all the benefits and protections he was afforded through the Federation.

Almost immediately, he and Ted got a weeklong gig playing with Lionel Hampton in Waikiki. Then they joined Don Ellis’s big band for a European tour. “I thought I’d really made it. It was my first time in Europe; we went to Switzerland and the South of France, where Miles Davis famously played,” says Kerber. “Then we came back and there was nothing, no work.”

Kerber had just begun attending college when he got a call to audition for a tour with Bette Midler. Only after he got the gig as second keyboardist, did he discover it also meant playing Hammond B-3 organ, Clavinet, as well as ARP Omni and Minimoog synthesizers.

“I’d never played an organ, and synthesizers I had no idea about. The drummer had to show me how to turn the organ on,” he says. A quick study and adept sight-reader, Kerber did well on the tour. When he returned home, he took a few synthesizer lessons and he started to get other calls.

“Carl Fortina, who was a big contractor in town at the time, called me for gigs at Paramount—Happy Days and Laverne and Shirley,” says Kerber. “If you could play piano, read well, improvise, play jazz, play rock, and knew how to work synthesizers, there was a much better chance of being hired.”

While his film and television work continued to grow, Kerber also got calls for album sessions. “My first big session was for Rickie Lee Jones for the Tom Waits song ‘Rainbow Sleeves,” says Kerber, who also played on Jones’ first album. “The people who knew me as a pop player or synthesizer player, didn’t necessarily know I was doing a lot of movie work too. I wore a lot of hats.”

Kerber also played on Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror.” He was keyboardist and orchestrator for the film Rush and Eric Clapton’s Grammy Award-winning song, “Tears in Heaven.” Among other artists he’s worked with are: Paul Anka, Leonard Cohen, Whitney Houston, Michael Bolton, Rod Stewart, B.B. King, Bill Medley, Annie Lennox, Art Garfunkel, Anastacia, Celine Dion, Natalie Cole, Al Jarreau, Ray Charles, Neil Diamond, Elisa, Julio Inglesias, Barry Manilow, Ricky Martin, Bette Midler, Corey Hart, Eric Burdon, Kenny Rodgers, Donna Summer, George Benson, Diana Ross, Marta Sanchez, Frank Sinatra, Jean-Yves Thibaudet and Dionne Warwick, and groups including Air Supply, America, Def Leppard, The Temptations, Manhattan Transfer, Lisa Stansfield, The Three Degrees, and A.R. Rhaman.

Thinking back to his first few film sessions, Kerber recalls being afraid of the violinists and feeling a bit like a deer in the headlights. “Everybody was so much older than me,” he says. “But when the red light went on I was very focused.” He recalls some of the early lessons he learned: “Always bring a pencil, don’t ask a lot of questions, get along with others, and treat the studio as the professional work environment that it is.”

“Relationships are very important in this business. Treasure the people you meet; it’s something you can potentially build on later,” he says. Among his mentors, Kerber names Composers James Horner and John Williams of Local 47 and 9-535 (Boston, MA).

“The ability to bring authenticity to different genres is the most important thing about being a studio musician; if I didn’t know the style or genre I would fake it,” he says. “What people don’t realize is that it’s a unique skillset to be able to read the music and bring a degree of performance to what you are reading. It’s like a good actor who can do a cold reading from a script and be in that character.”

Typically, musicians know very little about a project and don’t have an opportunity rehearse the music before they sit down for the session. Though, occasionally, the librarian posts the music to Dropbox a few days before. “You become adept at very quickly skimming a page. It’s like a golfer who can read the course and know by looking at it how the ball is going to fall,” he says.

At 27, Kerber was nominated for an Oscar with Local 47 members Quincy Jones and Jerry Hey for his work on The Color Purple. “It was the first time I conducted a huge 100-piece orchestra and Stephen Spielberg and Quincy Jones were in the booth. The music was by the famous trumpet player and arranger Jerry Hey who was a great mentor and friend. We started orchestrating and ended up writing. I wanted to conduct and when Jones asked if I could, Jerry said, ‘If Randy says he can, he can,’” recalls Kerber.

Among Kerber’s favorite projects was Forrest Gump. “I love the theme that Alan Silvestri [of Local 47] wrote for the piano—it’s very near and dear to me,” he says.

Though music plays a critical role in guiding the emotional flow of a film, it is traditionally left till the end. And the window of time composers have to complete their part of the film has shrunk in recent years.

“In the old days, the picture would have to be ‘locked,’ meaning no more changes could be done to the picture and you could start writing the music. Now, because it’s digital, a film is basically never locked, pushing the post-production process to the very end with a release date coming. Sometimes you get new revisions when you’ve already written to the last revisions. They’ll say, ‘We haven’t changed much.’ But they’ve snipped things out and all of the timings get thrown out the window.”

The timeframe for scoring the film can sometimes be as little as two weeks, he says. “For the most part, there isn’t enough time to get the music exactly the way you want it. If orchestrating needs to happen in a week, then the lead orchestrator has to pull in five or six people to help. It can be crazy!”

But, technology has also vastly simplified the work of orchestrators and composers. “There used to be a huge room in the back of the studios that stored the magnetic tapes where the music was recorded. Everything is recorded to Pro Tools now. And, as far as the music editor goes, streamers used to be directly scribed onto magnetic film, but now software does all the math for you,” he says.

For example, Kerber described his orchestration work with composer John Powell of Local 47 for the animated movie Ferdinand. “I got midi files and audio files, separated by strings, brass, and winds, of what he’d written. I did my work and delivered it electronically to the copyist. The first time I saw John was on the scoring stage,” he says.

“I love the orchestra and I love dotting all the I’s, crossing all the T’s, and making all the dynamics to bring some finesse to a composition. Because the composer is working very fast, the orchestrator adds the dynamics and articulations,” he says. “There is a psychology to how the music on the page looks to the musician. If there’s too much information it’s restricting; if there’s too little information they may not care. I feel like I bring a level of care that makes the musician interested in playing the music.”

While technology reigns in composing and orchestrating, on the recording stage it’s a different story, he says. “We still use microphones we used in the 1950s and 1960s—great vintage, classic mics. And we are still recording live orchestras and that’s fantastic! You cannot take away the magic of all those human beings with beating hearts playing in a room together. It’s unquantifiable. Instruments resonate. Sampled sounds don’t move through the air in the same way. When people walk onto a scoring stage for the first time and listen to a cue we play, the look on their faces makes my heart sing.”

Occasionally, projects come along where music is more central and there’s a longer timeframe for getting the music just right. La La Land was one of those projects. “It was a six-year passion project of Damien Chazelle and Justin Hurwitz of Local 47. The music for La La Land was worked on throughout the film and I came in early-on to lay down the piano parts for scenes that Ryan [Gosling] would be miming to,” says Randy.

“That’s a wonderful luxury and I think it’s something that could be wonderful moving forward, if a project can bear it. Having a composer attached to a movie sooner, having him work on themes, talk to the director about where it’s going, that would be a wonderful thing,” he says.

Kerber has a real passion for film work. And though it can be challenging, it is always exciting. “There’s new music all the time—always a new take on something. I like to bring as much life to it as I possibly can. I get a lot of pleasure from that,” he says. “The thing I tell young people is: be passionate about what you want. The love of what you do will manifest events in your life. I certainly didn’t think about the money; I just wanted to play music.” Fortunately, the AFM makes it possible for musicians to earn a decent career working on films.

At this point in his career, Kerber says it’s all word of mouth and he doesn’t have to make phone calls to get session and orchestrating work. “My track record speaks for itself and they know my name,” he says. However, he is hoping to move into more composing projects. “With every year, I feel more of a need to express myself as a composer. I think I have a lot to bring to the table from 40 years working in the business and with different composers,” he says.

The 20-minute live action short dramatic film Cello was the first film project entirely composed by Kerber. The movie stars cellist Lynn Harrell of Local 47 as master cellist Ansel Evans, diagnosed with ALS and facing the reality of losing his ability to perform. Kerber recorded a full-length soundtrack based on music from the film. Currently, he’s composing songs with songwriter Glen Ballard of Local 47 for an upcoming eight-episode Netflix drama called The Eddy.

He is also wearing the hat of journalist and executive producer for the show Underscore that brings together his years of experience and connections in the film music industry. “My friend, director and writer Gabriel Scott had the idea for me to talk with other composers about their childhoods, how they got started in the business—sort of the arch of a composer’s career,” explains Kerber. “I have interviewed Alan Sylvestri, John Debney, John Powell, and Marco Beltrami. We have a sizzle reel and are in the process of editing right now. It will be an hour-long show, but we haven’t sold it yet,” he says.