Tag Archives: Local 47

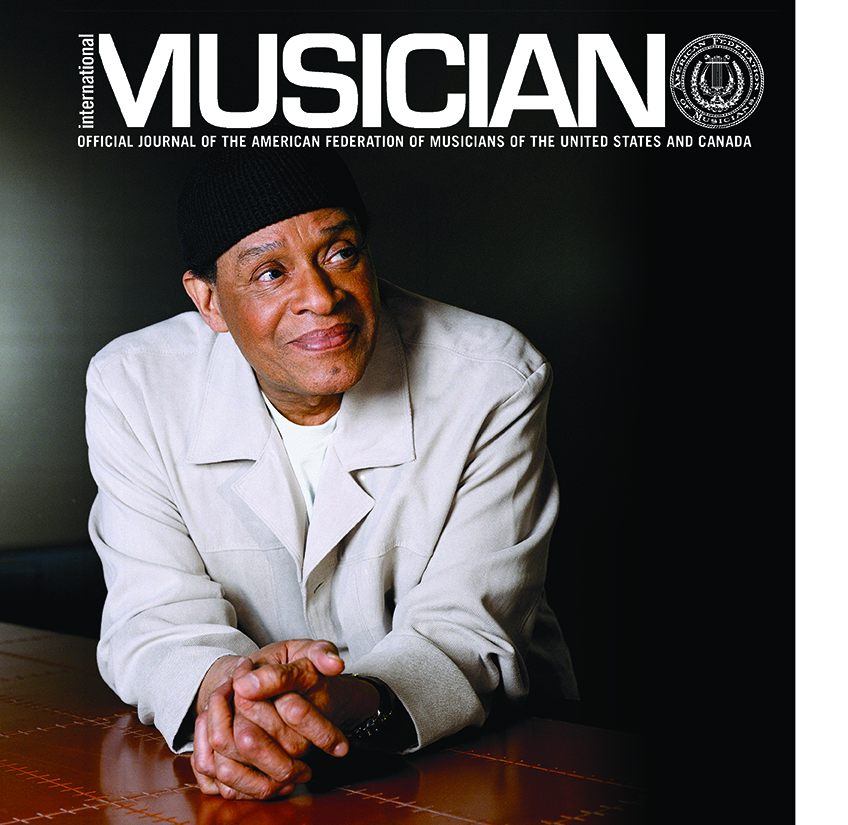

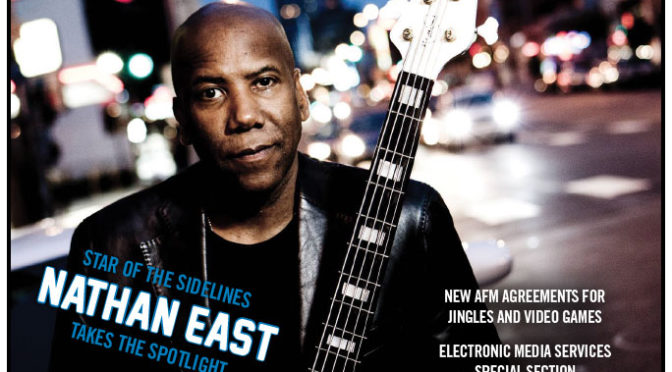

Nathan East

Grammy winning Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) member Nathan East is one of the most prolific working bassists of the last few decades. In 1984 he co-wrote the hit single “Easy Lover” with Phil Collins and Local 47 member Philip Bailey, launching a mind-boggling progression of successful, award-winning collaborations.

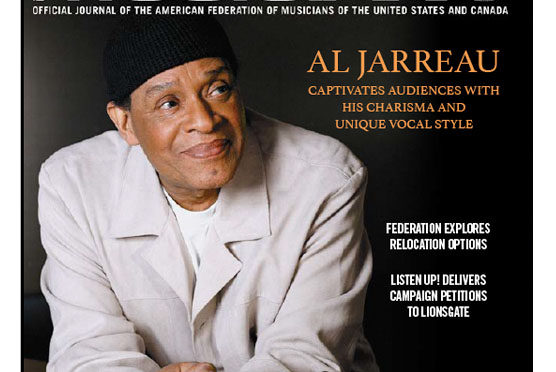

Al Jarreau: Ceaseless Creator of Fresh Sounds in Music

Ceaseless Creator of Fresh Sounds in Music

Al Jarreau’s innovative vocal style and vibrant personality have earned him wide appeal and Grammy Awards in three different genres of music: jazz, pop, and R&B. Continue reading

Quattro

Latin Blend Climbs Ranks as Captivating Quartet

After three years of hard work and sacrifice, Quattro feels honored to have been nominated for Best New Artist at this year’s Latin Grammy Awards.

The group prides itself on combining classical crossover with Latin American pop and contemporary jazz. The four members of Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) consist of cellist Giovanna Clayton, percussionist Jorge Villanueva, violinist Lisa Dondlinger, and guitarist Kay-Ta Matsuno (left to right in photo). The band strove to bring their debut release Popzzical into new territory, twisting a unique blend of genres.

“Diversity is the essence of the group and music is our universal language,” says Clayton. “The fact that a group made up of such different and diverse people can come together and create something so vibrant, soulful, energetic, and moving translates to an incredibly diverse audience. It is a testament to what happens when you respect and embrace each other’s differences.”

Critics continue to praise them, branding Popzzical as “eclectic, sun-filled, and introspective,” while emphasizing its virtuosity. The contemporary music community is also not shy in accepting Quattro, according to Dondlinger, who is pleased they have achieved this kind of recognition.

“Quattro represents so many cultures and so many genres, but at the end of the day we represent good music. This is what connects us to fans of all nationalities and all ages,” says Dondlinger. “Everyone has embraced it, especially musicians that come to our concerts. They are raving because we’re all from [different] backgrounds. We’ve studied our craft for so many years. Now, to put four musicians at that level [together], giving everyone a chance to shine and highlight each of their instruments, musicians are drawn to that because it’s such a great vehicle.”

Matsuno says that, when they raised money from Kickstarter, it generated a lot of response from fellow musicians and gave them a special connection with their fans. The musical community likes to support musicians who make decisions for themselves. A rewarding result of this is to receive credibility and praise such as a Latin Grammy nomination, he adds.

Though they didn’t win this year, just being nominated is like a dream come true, says Dondlinger. “As a musician you put your heart and soul into what you do never knowing what the response will be. It is always a thrilling surprise to be nominated for an award associated with your art.”

Popzzical presents an even balance of arrangements and original pieces, according to Dondlinger. Matsuno is responsible for a majority of musical arrangements, but each member contributes an individual flare to the group’s approach and songs that are written in both English and Spanish.

“There is no specific process that we go through other than bringing the ideas to the table and seeing how it organically grows from there,” Clayton adds. “What we’re trying to convey is unity from so many differences and essentially good music—soul music.”

As far as songwriting goes, Clayton or Matsuno will often work with ideas that were written a long time ago, such as starting with a famous classic composition, and adding a lot of different elements. For example, they may choose a piece meant for a jazz trio where Matsuno arranges it in a completely different fashion, preparing it for the tone of a violin, the harmony of a cello, and appealing rhythms.

“We do not spend much time composing, per se,” he adds. “We spend more time on arranging.”

Quattro’s blending of musical influences comes naturally. It’s not that the group is steering in any particular direction, according to Villanueva. “We didn’t choose any specific route,” he explains. “We all arrange [in] our own style and create this type of music.”

“That’s another reason why we had to create our own genre of music,” Dondlinger admits. “That’s why we call it ‘popzzical,’ because nobody could put it in any particular box, so we decided to create our own word.” The name comes from a combination of their main genres—Latin POP, jaZZ, and classICAL.

The group does not believe this approach separates them from their audience or alienates fellow musicians in any way. Instead, they feel that people gravitate toward it because it is something everyone can relate to. The members of Quattro feel they will continue to attract a broader audience because of it.

“I think it brings us closer to every one of our audience members,” Clayton says. “The beautiful thing is that, no matter who is listening, they can find something to relate to.”

Aside from their 12-song full-length album, Quattro revels in additional material celebrated in live shows that are often geared toward particular performance situations. For example, when performing in jazz clubs they will often play Local 36-627 (Kansas City, MO) member Pat Metheny covers, along with songs by Béla Fleck, a member of Local 257 (Nashville, TN), and Chick Corea of Local 802 (New York City). And, when playing for a more classical-driven audience, they focus more on a traditional crossover.

The group sees itself as breaking a lot of rules, Villanueva says. Combining instruments and music from around the world is a big motivation and inspiration to keep going, keep writing, and keep being who they are. He considers this attitude to be a lifestyle choice more than anything.

“I think music is so transparent [people tend to] see through musicians and I guess it’s my biggest inspiration to be able to communicate to the crowd where we come from as [artists] and human beings,” Villanueva says.

Clayton feels that the music itself is one of her biggest muses. Whatever training a musician may have, they are often not encouraged to explore other genres, she says. It took her a long while to realize why other musicians don’t dabble in a variety of styles. She considers herself lucky to have a connection to multiple genres and to have found other musicians to cross boundaries with.

Each member of Quattro says that joining the union was a valuable career decision.

Clayton joined the AFM at 16. The daughter of professional musicians, her distinctive cello method owes tribute to growing up in a multicultural household. She says that once you are in the union you are validated in the world of music, especially when working for orchestras. She plays with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, New West Symphony, and Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, and her résumé already includes a string of film scores, soundtracks, and TV shows.

Dondlinger became an AFM member in 2000, when she began work at the Henry Mancini Institute at the Frost School of Music, University of Miami. As a young adaptable violinist she has performed with top artists ranging from Celine Dion to Luciano Pavarotti, as well as house bands for American Idol, Dancing with the Stars, and The Tonight Show.

Born in Osaka, Japan, Matsuno was encouraged early in his career as a session guitarist to join the union. He joined about 10 to 15 years ago while playing with an artist on Virgin Records. It was one of his first recordings with a major recording artist and he credits Local 47 as being a huge help. Additionally, he says he is personally grateful to the union for its work lobbying for a law that grants musicians permission to carry their instruments on flights. Every time he went on tour it used to be a huge issue, according to Matsuno.

Villanueva joined the AFM during a Disney recording gig at Capitol Records. Born in Tijuana, Mexico, he continues to tour and play with high ranking Latin stars such as Christian Castro and Alexander Pires, as well as for TV Azteca, Univision, and LA TV. Villanueva is co-owner of Elefekto Music, film, and TV scoring company.

The AFM grants access to contracts, rules, regulations, rights, and more, the members explain. “Everything is very accessible,” Clayton says she’s glad the union is there to help negotiate collective bargaining rights, especially when it comes to performing in an orchestra.

She is also a member and representative for the Regional Orchestra Player’s Association (ROPA). “Going to that conference really opened my eyes to how important it is to all of us as musicians, and what the union does,” she says. “They not only negotiate contracts, but there are so many things happening behind the scenes.”

Clayton recalls one experience when the union came forward to defend her in an abusive work situation: they did not want to pay her properly. The AFM ensured proper legal representation and fought for equal working conditions.

“It is a really huge thing knowing we have that resource,” she adds. “I think musicians should make more of an effort to learn its inner workings and what the union is doing for us.”

It looks as though this year’s Latin Grammy nomination was probably only the first big honor for this group given it’s fresh outlook and sound. Future plans for Quattro include more tours, videos, and albums, all while reaching out to as many people as possible.

“We always say, ‘Please join our Quattro journey,” says Matsuno. “We think we are with our supporters no matter where we play and what we are doing. It feels great that we can take them on this amazing journey. This journey will go on for quite a long time.”

Local 47 Officers Participate in Civil Disobedience Action Against Walmart

In a preview of the nationwide day of action that took place on Black Friday, Walmart workers in several Southern California stores walked off the job November 7 to protest the company’s low wages. Walmart earned a profit of $17 billion so far this year, but pays its workers so little than many of them have to rely on public assistance programs to survive. Workers are also protesting Walmart’s retaliation against workers who speak out.

About 500 workers and supporters—community activists and union members, including more than a dozen Local 47 members and officers—participated in what was the largest civil disobedience action in Walmart history. Surrounded by about 100 police officers in riot gear, and with helicopters circling above, 54 protesters were arrested outside a Walmart store in Los Angeles’s Chinatown section. Among those taken into custody, after refusing to leave the peaceful demonstration organized by the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor when their permit expired, were AFM Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) Vice President John Acosta and Secretary-Treasurer Gary Lasley.

Local 47 members (L to R), standing: Lynn Grants, Maurice Grants, Alan Busteed, (unknown), Vice President John Acosta, Joseph Hancock, Robin Lasley, Secretary-Treasurer Gary Lasley, Neil Samples, Ethan Harris; kneeling: Naomi Sato, EMSD Administrator Gordon Grayson. Photos: Linda A. Rapka

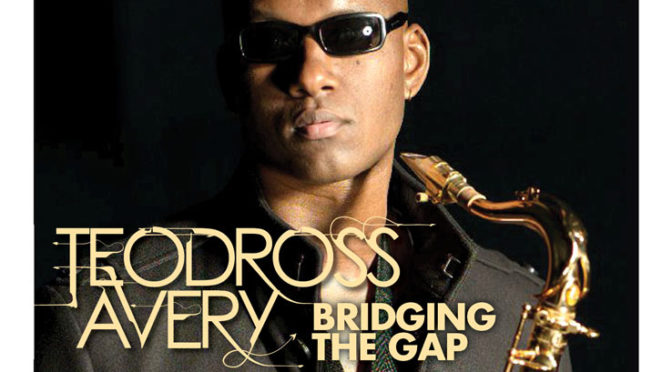

Teo Avery

Student of Saxophone

Saxophonist Teodross Avery got a jump on his career, scoring a record deal in college. Then came opportunities to work with everyone from Aretha Franklin to Tommy Flanagan, and even Matchbox Twenty. Today, he can be found on the University of Southern California (USC) campus where he is teaching and working on a doctorate. The Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) member shares his philosophies on jazz, saxophone, and life.

Avery credits his father for the gift of music. “My father loves music and has an extensive vinyl collection,” says Avery, who listened to everything from soul to rock to jazz growing up in Northern California. “He always wanted to give me music because he thought, no matter what kind of sorrow or loss I might experience, music would be there to comfort me. He pushed me to get lessons on guitar.”

Avery switched to saxophone after hearing John Coltrane’s Giant Steps as a teen. “It just blew my mind. What he was saying musically spoke to me: the high level of sound through his instrument and the complexity of it. On an emotional level, there was such a level of urgency in his music. It pulled me right in,” he says.

From then on, sax was his instrument and jazz was his genre. He would play every chance he got, and when he wasn’t playing, he listened, going to hear all the jazzers as they passed through town.

And he always brought his saxophone, just in case. “My dad always told me to bring my horn along and ask if I could play with them,” recalls Avery. “I got to sit in with some incredible musicians—Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, and Freddie Hubbard.” He frequently asked famous sax players to write out licks for him.

“Those moments I learned a lot,” says Avery, and it wasn’t just the music. “They passed on something through the music, a spiritual connection between life and music; I’m so happy that I got to receive it, even for a short time.”

The precocious kid even managed to get a new saxophone from Local 802 (New York City) member Wynton Marsalis. “I read that he would purchase instruments for deserving students. I wanted to sit in with him, but I also needed a new horn, so I asked his manager and they arranged it,” he recalls. “To this day, I’m extremely thankful, not only because they bought it for me, but because they made a connection with a young kid who wanted to play music and better himself.”

“The best advice I ever got was from a bass player who played with Pharoah Sanders. He told me to practice eight hours a day,” recalls Avery, who was about 15 at the time. “That summer I practiced six to eight hours a day and really connected with the instrument.”

“It shaped my thinking, regimented my musical schedule, and made me think about notes and math as it relates to music,” he says. “It pushed me to think about interpolations, and then transfer that to other parts of my life. It made me think about music in a deep, deep way that will forever influence me.”

Avery was awarded a full scholarship for Berklee College of Music. And although he got a record deal and released the album Other Words at age 19 (1994), he continued studying. His decision to stay in school was partly due to his parents who were adamant that he complete a degree, as well as other musicians who told him he should keep studying.

“There were moments when I thought about leaving,” says Avery, who recalls advice he received from sax player Antonio Hart, who was on the road with Roy Hargrove during his college time. “He told me how he did it. So I stuck with the plan, and whenever I’d go on tour, I’d bring the homework and do it on the plane or in the hotel room.”

Educated from school and the music scene, simultaneously, Avery appreciates the value of each. “What you get from college is clear music theories, or clear ways to approach music in a regimented form. Information is spread over 15 weeks, so you gradually learn it,” he says. “Being on the music scene has its pluses too; you are able to get a deeper level of study in an area. And learning how to bob and weave socially, you are not going to learn that in school.”

After graduating Berklee in 1995, Avery jumped

head first into the New York City music scene. He eventually went on to get his master’s degree in music from Steinhardt School of Education at New York University, and released four more albums, each demonstrating a distinct evolution in his music.

“Those albums represent what I was seeing around me socially,” he explains. “As an artist, you have your set of objectives and society’s set of objectives. You could tell your story, but if you wanted, you could tell the story of yourself as it relates to society.”

“The first album was a hard-core young man’s perspective,” he says, explaining that up until that point he was totally jazz-focused, and not interested in contemporary music at all. “After, I was able to travel and go outside my comfort zone, hearing different groups, I started to be aware of what was going on around me musically. I had reconnected with contemporary society, so my jazz started to change.” My Generation [1996] is a result of these brand new influences.

He slowly became totally immersed in life as a New York musician. “At the time that New Day, New Groove came out [2001] I was checking out a lot of different cafés in New York. I wanted to keep putting out music, but I was no longer with the label,” he says, adding that the album was put together through “a hard core bartering process.”

In 2006 his sound changed when he began using Cannonball saxes, which have larger bells and tone holes to accommodate a larger spectrum of sound. “I could play very loud or very soft and I didn’t have any resistance from the horn. Those horns reinvigorated me as a saxophone player,” he says.

Bridging the Gap [2008] was his first self-produced album. “I did that album after having a lot of hip-hop sessions and live shows with artists in New York. I pretty much programed the whole album from beginning to end; I was making my own sounds and mixing.”

The title of Avery’s 2009 album, Diva’s Choice, comes from the fact that, around that period of time, he performed with a lot of different female artists. “I recorded and produced a song with Amy Winehouse on her first album, I played with Lauryn Hill, Shakira, Leela James, Joss Stone—outstanding women and outstanding performers,” he says.

Throughout these many projects, Avery has remained a member of the AFM, first joining Local 802 (New York City). “I needed a legal body to speak on my behalf,” he says. “The union makes sure musicians are protected.”

Now, at 40, after having recorded or played with a huge range of artists, appearing in two films, and on numerous television shows, Avery has returned to school.

“I’m very happy about where I am right now,” he says. “I didn’t want to be a freelance musician in New York anymore, so I left. I got some great experiences, I played with some great artists. I have no regrets. What I gained is more of my ethos on life: do what you do best, let people know about it, and keep on creating and being productive.”

He says there are two reasons why he decided to come to USC to teach and work on his doctorate. “I played so much jazz and contemporary music that I was never really challenged to perform or write classical music, so I felt like I wanted to bridge the two together. Also, I get to study jazz and learn from people—Bob Mintzer is here and so is Alan Pasqua. I’m getting their perspective on music as well.”

“The point is to add it all together, and over time you have experience to deliver a broader perspective and different angles as a teacher,” he says, something he has become passionate about. He even teaches remotely through Skype, arranging lessons through his website (teodrossavery.com).

“I enjoy teaching, but I also enjoy learning,” says Avery of his education-focused life. “I enjoy the process of learning, walking into new situations that I didn’t understand before and walking away feeling, ‘Wow, I was humbled by something; now I can think about life in this other way.’”

“I’d like to continue to teach and start a music education nonprofit relating to discipline and how to approach music from a philosophical perspective, as well as a musical perspective,” he explains, reflecting on what music has meant to him in his life. “Music is just one part of a larger perspective of life and I’d like to make that a little more clear.”

As for his ethos to “keep on creating,” Avery has two albums in the works that once again explore extremes. One is an acoustic jazz album of popular songs, which is recorded and just needs to be edited and mixed. “I was purposely trying to make the point that you can make jazz more palatable for the general public,” he says.

He’s currently writing songs for a disparate album. “It’s going to be a hard core jazz album—compositionally complex, artistic jazz without regards to what somebody might want to hear,” he says. “I haven’t done that since my first album.”

B.B. King: Travels with Lucille

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.

Local 71 (Memphis, TN) member B.B. King and his guitar Lucille have traveled to 90 different countries together.

It’s a freezing winter night in the1950s in Twist, Arkansas. In a little club, people are dancing to a young blues guitarist. The warmth of their moving bodies heats up the place, as does a small kerosene stove in the corner. Two fans begin pushing one another over a woman named Lucille who works in the nightclub. They knock over the stove, and a river of flames engulfs the place.

People scramble for the doors. Once outside, the guitarist realizes that he has forgotten his $30 acoustic guitar inside the building. He rushes back into the searing heat. “It was hard to get instruments and I thought only of getting my guitar out of there,” says the guitarist, who goes by the name B.B. King these days. King, a member of Local 71 (Memphis, TN), named his guitar after the woman to remind himself never to do something so foolish as rushing into a burning building to save an instrument. These days, a wiser King, who is currently touring with Lucille XVI, would only commit a similar act of bravery to save a human life.

King’s 51 years as a recording musician and tour stops in 90 countries have ensured that Lucille is a name familiar to blues fans worldwide. Lucille has become a signature model guitar manufactured by Gibson to King’s specifications, and she’s taken the musician from the juke joints of the South to Carnegie Hall.

Money In the Hat

Today, King, who once made 35 cents a day picking cotton, is a multimillionaire as a result of his music. His most successful album, “Riding with the King,” in collaboration with Eric Clapton, came out when King was almost 75. It sold 4.5 million copies worldwide, and it’s estimated that, over the course of his career, King has sold over 40 million records. Mere financial gain, though, is not all that King has earned from his particular version of the blues. He has also been awarded five honorary doctorates from institutions as prestigious as Yale University and the Berklee School of Music.

These accomplishments are nothing short of amazing, considering that King started out on the street corners of his hometown of Indianola, Mississippi. In those days, King aspired to be a gospel musician, idolizing a local preacher who played guitar in church. Experience on the corners, however, sent him down a different path.

“When people would ask me to play a tune, if I played a gospel tune, they would always praise me highly, but hardly put anything in the hat,” he recalls. “People that asked me to play blues would always put something in the hat. That’s why I’m a blues singer.”

It didn’t take long for King to outgrow street corners. At 20, he traveled on the back of a grocery truck to Memphis, carrying only his guitar and $2.50 in his pocket. A few years later, King landed his own 10-minute radio show on WDIA, called the “King Spot.” On every show, he sang the sponsor’s jingle, “Pepticon, Pepticon, sure is good/ You can get it anywhere in your neighborhood.” Thus, the Pepticon Boy, as he was known, took the first step on his path toward musical legend.

New Opportunities, New Name

The “chairman of the board” belts out the blues in concert for dedicated fans.

King’s show was so popular that he was soon offered a job as a DJ. He played records by artists such as Sarah Vaughan and Frank Sinatra, who would one day invite him to share “booze and broads” in Las Vegas. Before he could achieve the level of success that allowed him to hang out with Sinatra, he was told to change his name from Riley King to something catchy. For a while, he performed as Beale Street Blues Boy, then just Blues Boy King, until he finally shortened it to B.B. King.

To many black teenagers in the 1960s, blues was their parents’ music, largely a thing of the past. One of King’s hardest moments was at the Royal Theater in Baltimore, Maryland where he was booed by a young crowd that wanted to see the hot young acts on the bill, Sam Cooke and The Drifters. It stung King to be treated poorly, but as a sharecropper’s son from the South, he learned how to achieve his goals in spite of people’s cruelty.

“You knew it was something you had to do,” he says, likening that moment in Baltimore to racial difficulties from his childhood. “You’d go ahead and do the best you could, thinking you’re by yourself, that nobody cares. Life goes on.”

That same determination characterized King’s early career. He first recorded in 1949, including a song named after the first of the two wives he has had, “Miss Martha King.” It wasn’t until 1952, when he released “Three O’Clock Blues,” that King’s music caught on. The song, which was recorded in the back room of a Memphis YMCA, put places like Harlem’s Apollo Theater on his touring itinerary. King developed a distinct musical style in the ’50s through constant touring. In 1956 he played 342 shows, taking the sounds of influences such as T-Bone Walker and Blind Lemon Jefferson and combining them with other musicians he loved, such as jazz guitarists Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian.

Growing Reputationand Rapport

This extended period of success culminated in the 1965 album, “Live at the Regal.” The album is still a favorite with fans and critics alike, partly because of the precision of the guitar work, but also because of King’s rapport with the crowd. Some of King’s most important fans at the time were the white rock musicians who borrowed heavily from the blues to develop their sounds. In a 1966 Crawdaddy interview Mike Bloomfield, guitarist for the Butterfield Blues Band, said, “B.B. King is one of the greatest guitarists who ever lived and more people should listen to B.B. King’s records.”

Legendary rock promoter Bill Graham took Bloomfield’s advice and booked King to play at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. When King pulled up to the club, he thought he was in the wrong place because of all the long-haired white kids milling around outside. He worried that he might get booed. King didn’t usually drink before shows, but was so nervous that he asked Graham to get him a drink. Graham got a whole bottle of whiskey for the anxious artist.

After a short introduction by Graham, who called him “the chairman of the board,” the crowd went wild. They gave King his first standing ovation that night. The 43-year-old blues giant was so touched, he cried on stage. In a recent PBS documentary on the blues, King still got choked up recalling the moment.

It was a turning point for King that signaled the direction his career has headed in to this day. King says that, in his early days, 90% of his audience was black and his age or older. Today, King says his audience is much younger than he is and 95% white. This is partly a result of musicians who have incorporated King’s blues into their own music.

King is thankful for the help he received from devoted fans such as Eric Clapton and Eric Burdon.

“People didn’t value what we did as anything special until the British groups started playing what I call Real Important Blues, and white people started to pay attention to it,” he recently told The New York Times. “These groups played it, supported it, and opened alot of doors for B.B. King and a lot of people like him,” the article’s author commented.

Strength in Numbers

B.B. King released his most popular and succesful album at the young age of 75.

A lot of doors were opened for King by the AFM as well. The blues chairman joined the union in 1949 because it promised “better wages.” He is most grateful, however, for the protection the union offered him.

“It’s an old and true saying, ‘there’s strength in numbers,'” says King. “Sometimes you’d go places and people wouldn’t pay you. The union was good then, because they’d put them on the unfair list and nobody would go and play for them.”

While the AFM helped King deal with the less pleasant aspects of the music business, the MP3 player that travels everywhere with him helps remind him why he chose to be a professional musician early in life. He keeps the music of his influencesWalker and Jefferson, as well as Lonnie Johnson and Muddy Watersclose at hand so that he can revitalize his passion for the blues at the push of a button. King says that listening frequently to his idols ensures that his music does not depart from what he cares most about.

King’s performances today give no indication that his success has taken away his feeling for the blues. Just like he did long ago that night in Twist, Arkansas, he makes people want to dance. When he’s up on stage, he plays for the crowd, not for himself. That’s why, from a sitting position, he and Lucille still have the power to bring people to their feet.

King says he performs every song as if he hasn’t played it before. This simple yet highly effective philosophy, shared with his band to prevent songs he has played for decades from becoming stale, underlines why he has continued to nurture an avid international following.

“Play it like you feel it,” he says, repeating what he tells his band. “Don’t try to play it like you recorded it 10 years ago. Play it today, like you feel it now.”

Visit the official B.B. King Web site at www.bbking.com.