She asked for a drum set. She got a banjo. The rest is jazz history.

As a child, Cynthia Sayer got bribed by her parents with a banjo—and ended up finding her musical niche.

Sayer found her first musical love in the piano, which she started playing at age six. She also learned and played viola in elementary and middle school, taught herself to play guitar chords and played orchestral drums. Then one day, still in middle school, Sayer saw a jazz band perform and decided she wanted a drum set. Her parents, however—who raised four children and fostered music appreciation and participation—drew the line at drums in their house.

“I came home from school one day and it was sitting on my bed. I hardly knew what it was: There was no roots music in my world—“Hee Haw” on TV was about my only idea. I knew it was a bribe, but I thought, ‘OK I’ll play it.’” says Sayer, a member of Local 802 (New York City). “So why a banjo? Because they saw an ad from someone offering to teach banjo. It was a female player named Patty Fischer who moved to our town offering lessons.”

This was the beginning of Sayer’s jazz banjo career that is now world-renowned, award-winning, spans every type of performance (live and session; albums, movies, TV; solo, orchestral, and ensemble), and has contributed to posterity through teaching and advocacy. It is a career that has succeeded in the face of gender bias, a general misunderstanding and disrespect for her chosen musical instrument in jazz, and the common musician’s battle to be respected, relevant, and, ultimately, paid to play.

“Patty was the coolest grownup I had ever met—I had never met a woman in the arts before,” Sayer says of her first banjo teacher. “I was totally knocked out by this; she became very important to me.” While today it may sound strange or anachronistic, when Sayer started learning and ultimately playing music professionally, there were not many women in her field— and even fewer in her genre. “I spent 15 years touring internationally before I worked with another female player,” she says. “I would walk into a room with my banjo—and being a woman—and people would be like, ‘What on Earth?’ I was a walking double whammy, which caused a lot of challenges. That’s not the case so much now. It’s been years since I’ve heard, ‘Which guy in the band is your boyfriend/husband?’ or ‘You play great for a girl.’”

Sayer began her music career as so many musicians do—by not intending to be a professional musician. She attended Ithaca College in New York State, where she majored in English and drama and planned to attend law school. When she was not studying, she was freelancing with her banjo to make money. Instead of going to law school, Sayer went on tour with the USO right out of college, playing in Germany and Iceland, and afterward coming back to the States and settling in New York City. She became a successful freelancer pretty quickly because she found a need for banjo players. “I consider myself to have learned apprenticeship style: I learned by doing with some amazing players,” she says. “I remember being so naïve in my 20s, thinking musicians were so nice and helpful. Later I understood they stuck with me because they wanted me to improve,” she laughs, “and they saw that I wanted to learn and I was serious about it.”

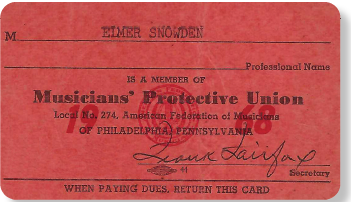

While Sayer can and does play every genre of music on her banjo—classical, tango, country, bluegrass, for examples—she is primarily a jazz player. She discovered jazz—and jazz banjo—through Elmer Snowden’s 1960 album, Harlem Banjo! “I was absolutely dumbfounded,” she says. “When I heard that album, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. That was the end of it for me with all other kinds of playing. I wanted to play true, serious, driving jazz.” One of the first things Sayer did after that realization was transcribe all of Snowden’s jazz solos.

When people think of banjos, they typically think of the five-string version that is used primarily for bluegrass music and often played by fingerpicking. Sayer plays a four-string banjo and uses a plectrum. The differences between the two types of banjos is like the difference between a trumpet and trombone, she says. The attack is different, the mechanics of playing are different, even the sound is different. But one way they are the same is that banjos have a long history of being overlooked or misunderstood, Sayer says.

“Banjo is the original fretted instrument of jazz, yet the jazz world has such trouble including it,” she says. “The banjo is an extraordinarily powerful instrument with an earthy, interesting sound. I love its drive and the power behind the drive that it has to offer,” she says. “This combination of honest, earthy roots, kind of the twang part of it, can be applied in so many wonderful ways, but I think people just understandably think of it in the way they know best. So I make the point to play all kinds of music … just to try to show the versatility of it in my programs.”

And Sayer certainly has versatility with her chosen instrument. She first rose to international prominence as a founding member of Woody Allen’s New Orleans Jazz Band, in which she played piano and banjo and did vocals. She simultaneously explored her wider musical interests playing with such legendary jazz, popular, and roots music artists (and AFM members) as Bucky Pizzarelli, Dick Hyman, Les Paul, Marvin Hamlisch, and Wynton Marsalis. Her extensive career includes playing banjo, ukulele, and piano on feature film and TV soundtracks—including several Woody Allen films, the classic movie Sophie’s Choice, and the Sesame Street soundtrack— and doing TV commercials and radio jingles. She has busked in the streets, performed for two U.S. presidents (once at the White House), played with orchestras and at the Met for the American Ballet Theatre, and even had a gig with the New York Yankees promotional band, for which she was featured in a Trivial Pursuit question (see sidebar).

Sayer has made nine albums, received numerous awards and accolades, and written a book titled You’re IN the Band. In 2006 she was inducted into the National Four-String Banjo Hall of Fame, which is part of the American Banjo Museum.

Despite this stellar resume, being a female musician has been a major factor throughout her career. While she rarely receives the backhanded compliments or flippant comments about being a girl player that she did decades ago, she still sees that women in the music industry have a long way to go for equality. “I have a feeling of disappointment that I see so few women like me—middle aged, working instrumentalists—out there. But I am so happy and grateful to see young women who are coming up now, and their activism,” Sayer says.

Similarly, she finds the cultural stigma of the banjo is also finally being shed. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the banjo typically was seen as the instrument of low-income classes of people, both black and white, that was used for casual recreation at home or in minstrel shows—not for “serious” musical endeavors. Sayer says players such as Bela Fleck (member of Local 257 in Nashville) and others have helped change the perception of the banjo and undo the musical stereotypes that have followed the instrument for over a century, while movements for Black players to reclaim the banjo and embrace its African roots started in the 1990s. “It’s uncanny how the banjo has a long history of reflecting our society, and even now, in keeping with our powerful #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, it continues to reflect our social evolution in diversity,” Sayer says. “The banjo is now recognized as the core of a whole part of America’s musical heritage that had been swept under the rug. … After all this time, it’s like the banjo—both 4-string and 5-string—is finally truly coming into its own.”

She views this positive forward movement as encouraging, and even sees an opportunity for greater advancement because of the current coronavirus pandemic. “It makes you think about what you appreciate because you’re stuck at home and feeling grateful for what you have. I was thinking this is a good time for musicians to look around and really see the talent that they may be overlooking in women and people of color—or in whatever bubble they happen to be in—whether it’s about culture or gender or sexual preference,” she says. “There’s so much great talent out there, and if you really notice and pay attention, you will appreciate it. … Then you would have to be more inclusive, because I think there is still a bias out there—whether it’s just from habit, conscious or unconscious—but whatever it is, we need more women in the music industry. I’m an example of the fact that you can do it, and I want other women to have the opportunity to do that too.”

Cynthia Sayer Recounts Times the AFM Had Her Back

Cynthia Sayer has been an AFM member for over 40 years. She originally joined as a college student in Ithaca, NY, in the 1970s. She transferred to Local 380 (Binghamton, NY) when the Ithaca local closed, and recently transferred her membership to Local 802.

“The AFM has been overtly helpful to me! I was not properly in the system for some soundtrack work I did early in my career—i.e. in pre-digital times—although I had signed union contracts for each. Two were successful feature films and one was a television series. I was foolishly naïve about royalties then, and thought, ‘Oh well, at least I was paid properly at the time, and enjoyed the experiences.’ I let it go and moved on.

“Years later, older and wiser, after accidentally discovering I was also on the cast album for one of the un-credited films, I was reminded of it all and called the Film Musicians Secondary Market Fund to see if anything could still be done. They explained what I needed, and then I called the union for help. The man I worked with there [at Local 802 (New York City)] was fantastic! He doggedly tracked down what was needed, aided by a couple items of proof I was luckily able to dig up for one of the films, and he succeeded in getting me into the system for all of my missing work. Thanks to the AFM, I finally received—and still get—those royalty payments.

“I reached out to this same wonderful man at the union a few years ago, after receiving a questionable letter from a film company for whom I had done some soundtrack work, and for which I had signed union contracts. Reading the legal jargon, it appeared to me that they were asking me to sign away my soundtrack rights! He confirmed that’s exactly what it was, advised me to not sign it, and expressed profound gratitude to have been informed about it so that they could be aware of and fight this kind of underhanded activity. I continue to receive my royalties for this work as well.

“As you can see, the union has made a real difference to me. They’ve demonstrated that I can count on them to have my back for contracted work.”

Q: Cynthia Sayer was hired to be the official banjo player of what Major League Baseball team?

This question was included in the game Trivial Pursuit (1998 edition). The answer? The New York Yankees.

Being part of a popular 1990s board game is something that Sayer is both proud of and gets a kick out of. “No matter how much I bury this information, that is a thing that people always ask me about,” she says with a laugh. Sayer is not even a baseball fan—it was just a gig she did playing in the Yankees’ promotional band for eight years during the 1980s and 1990s. She was part of the primary “A” band that would perform during games and special events, moving around the stadium, mostly behind home plate and for the more expensive seats. While games were going on the band would sit and watch, and during breaks they would play for the fans. “This was a sought-after gig for baseball fans,” she says. “And I think I was probably the only one in the band who was indifferent to baseball.”

Sayer got to meet the ballplayers, see various celebrities in the box seats, and experience some World Series games, but those are not the moments that stick in her memory. “I remember we had to wear these Yankee outfits that were about 20 sizes too big for me; they were like giant flannel pajamas,” she says. “We would get on television all the time and I would always try to pull my baseball cap over my face because I was embarrassed to be on television. And my poor mother, who despised sports, would sit there and watch the whole game waiting for those occasional moments.”

Sayer remembers the few times the band went up to the press box, which was “a completely different sonic experience” than being down in the stadium, she says. Up there, away from the crowds, it felt intimate, personal, and quiet; you could hear the crack of the bat when it connected with the ball, and just absorb a deeper connection to the actual sport, she says.

Another memorable moment was being fired by George Steinbrenner.

During one special event day, there were multiple promo bands playing outside the stadium as fans arrived. One of the bands (not the one Sayer was in) was playing at the spot where Steinbrenner would always arrive at the stadium. Unfortunately, the moment he arrived was the moment the band was on break. “He got out of his limo and saw the band wasn’t playing and was furious—and fired everybody.” Sayer says. “I thought it was kind of funny. … It was part of the adventure of the gig for me.”

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Cynthia Sayer endorses:

‡ Ome Banjos

‡ GHS Strings

‡ Blue Chip Picks

‡ The Realist Banjo Pickups by David Gage