A Musician’s Perspective: Gaelen McCormick, Local 66 (Rochester, NY)

For more than 20 years, I was a double bassist with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and for at least 10 of those years I sat directly in front of the brass section. They were on risers and their bells pointed at the back of my head. Pretty early in my career I started to lose some hearing in the higher frequencies on the right side. The left ear was spared by the shielding effect of my skull as the sound hit my right ear sooner and with more intensity. While my brass colleagues are wonderful musical players, there is simply no avoiding the full impact of their sound. I was fitted with a custom earplug for the right ear and although the sound was uneven—the left ear is open, while the right ear is “filtered”—over time, I adjusted.

I wouldn’t have known that I had suffered hearing loss had it not been for an unusual experience flying back from a gig. My ears never “popped” or returned to regular pressure after that flight. After a week of trying all the tricks I knew, I gave up and went to the audiologist for help. A hearing screening, which was part of the workup at the clinic, revealed an audiometric notch in my right ear.

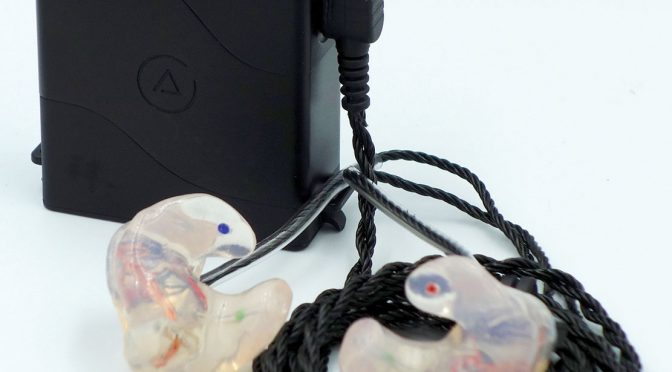

Because I developed Meniere’s disease in my left ear (the “good” one), louder sounds became increasingly painful. It was time to get a second custom earplug. At this point I realized that I needed to practice more often with earplugs so that I didn’t feel isolated or “underwater” when I was on stage. But honestly, with the filters that come with the custom plugs, there is only slightly less volume, and the clarity of sound is still there.

I do get regular hearing screenings because of Meniere’s disease. What’s more, routine monitoring has been helpful to confirm that the custom plugs are, in fact, helping and I am not experiencing additional hearing loss on the right side. This disease has already caused deafness on one side, and I know too well the stigma of hearing loss in the music community. My advice is to get a baseline hearing test now. To maintain a long and healthy career, be proactive and work to conserve your hearing by using hearing protection throughout your career.

An Audiologist’s Perspective: Heather Malyuk, AuD

I’ve been a specialized music audiologist for nearly a decade and part of the music industry for most of my life. It was providence that led me to the field of audiology when I was looking for a new career path. I saw an online advertisement for a Doctor of Audiology program. Yes, it took looking for a new career to lead me to hearing health.

What’s striking about that statement is that I have a music degree, I was in three youth orchestras growing up, and worked for a number of years as a professional musician. When I think back on my early musical life, despite being surrounded by wonderful teachers, hearing was never discussed.

As soon as I began playing, or at least as soon as I started youth orchestra, I should have learned about the sense of hearing and audiology. Why? Ear training. If I had the chance to practice with hearing protection while developing my listening skills, it wouldn’t be so difficult to wear earplugs now.

In nearly a decade of clinical practice, a resounding comment from players, especially classical orchestral musicians, is: “I love my earplugs, but wish I’d known about them when I was learning to play. I have so little time to practice with them and get used to them now.”

Earplug sound quality is not the same as the open ear canal and training with earplugs is a bit like becoming bilingual (or “bi-aural”). It’s a skill more easily honed as a youth. An additional bonus to early training with earplugs is preservation of hearing and staving off music-induced hearing disorders (MIHD). Sound injury to ears is permanent. As such, an ounce of ear training is worth a pound of cure.

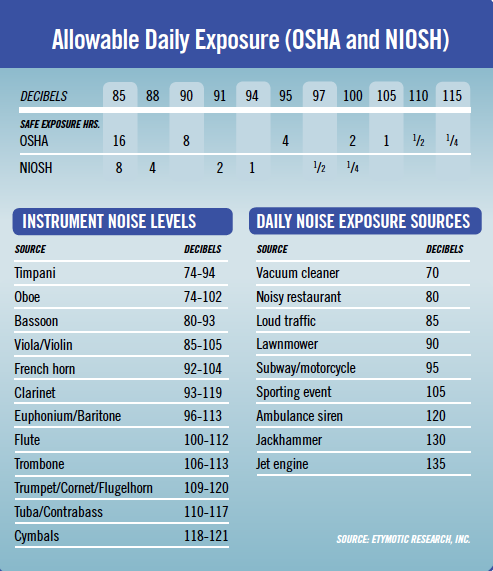

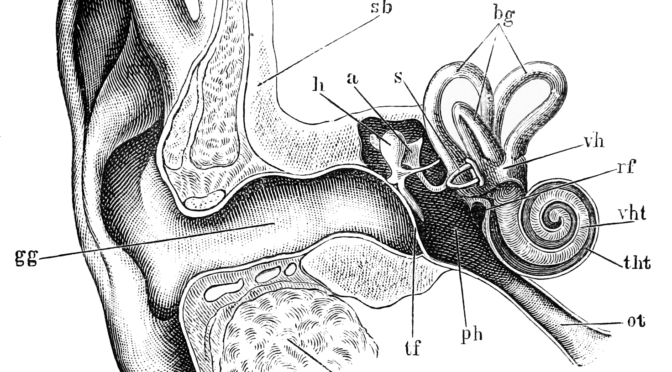

The primary goal of hearing conservation is to prevent MIHD such as tinnitus (ringing), distortion, pitch perception issues, sound sensitivity, and hearing loss. Research shows that musicians are at risk for these disorders regardless of musical genre. Sound-induced hearing loss primarily occurs in two frequency regions: 3000-6000 Hz and above 9000 Hz. This is different from typical age-related hearing loss, which tends to affect only higher frequencies of hearing.

Unfortunately, musicians who have hearing loss without accompanying disorders can often “ear train” to the loss and work effectively until it becomes severe. This can be dangerous, as hearing loss from sound occurs gradually. Without annual hearing evaluations, it can go undetected for years.

Too often I see musicians who are beginning to have difficulty with timbre, pitch perception, or hearing in general, who have not been tested in over a decade. In some instances, the loss could have been prevented entirely. There are other factors of hearing loss, either caused by genetics, disease processes, medications and medical treatment, viruses, and more. For these, it’s essential to have an audiologist who is specializes in hearing as it relates to music and associated needs.

What’s the bottom line? Every musician should have annual hearing tests, early adoption of protection, and a relationship with an audiologist. Audiologists are the gatekeepers to every musician’s main instrument: the auditory system.

—Gaelen McCormick of Local 66 (Rochester, NY) is a double bassist who was a member of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra from 1995-2017. She is program manager of Eastman Performing Arts Medicine. Heather Malyuk, AuD, owns and directs Soundcheck Audiology.