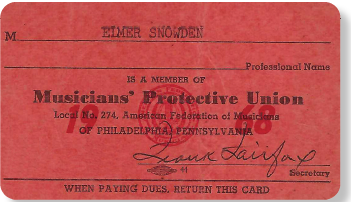

As the world continues to anticipate the mitigation of COVID-19, after two historic years of tragedy, conflict, disruption, and innovation, the Music Performance Trust Fund (MPTF) is planning for a return to uncompromised live music performances. While adjustments will be made should the pandemic continue, the MPTF is eager to support high profile, live, admission-free music events, including music education programs, as well as performances in senior centers, assisted living facilities, and community venues throughout the US and Canada.

The MPTF and AFM locals have coordinated more than 224 admission-free concerts for April to celebrate Jazz Appreciation Month. It is a fresh sign that musicians and audiences are ready to re-engage in the joy and appreciation of great music performed live.

I am happy to report that our 2022-2023 fiscal year grant budget will increase from $2.2 million to $2.5 million, inclusive of the National Fund for special projects. Our senior center/assisted living initiative, MusicianFest, budget of $200,000 will be allocated separately as a supplement to the general grant budget. Local grant coordinators and local officers have been informed of the relevant allocations by state/province.

Additional funds will be made available to support the MPTF scholarship program that was launched in 2020. In total, the full grant allocation is $2.85 million. This is an increase of approximately 30% over the total distribution target for 2021-2022 and is the largest grant budget in over a decade.

With the expected return to a full slate of traditional live performances, MPTF has been preparing new promotional materials. A fully updated and comprehensive edition of the trustee’s regulations was sent to each local to provide guidance on the grant rules and how each local can implement a grant submission. Our grant management team is always available to help clarify any issue in the grant application process.

The MPTF has also created a series of marketing tools to promote our sponsored and co-sponsored events. These include large free-standing banners that are personalized for the more active locals. Standard versions will be available to all locals who are actively participating in our grant resources. Traditional posters will also be available, along with flyer templates, which can be accessed online to print physical copies and to use on social media.

Near the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, in May 2020, MPTF launched an online streaming initiative that delivered over 1,200 grant-supported live performances. We intend to continue this approach to bringing admission-free concerts to the public as part of our community events program.

The MPTF will provide matching funds (50/50) for all community events in parks and public spaces and will require a local community co-sponsor. MPTF has created brochures as a tool to help encourage community co-sponsorship and explain how to secure our funding. Locals can request both printed and online versions of the brochure.

There is no guarantee that MPTF annual grant budgets will continue to increase in years to come. Therefore, it is essential for locals to seek civic partners to expand the influence of MPTF grants to increase live music’s impact on the community.

MusicianFest will continue. Interested locals will be provided an allocated number of performances by our grant management team. Similarly, the Music in the Schools programs will be fully funded but maxed at 25% of the local’s overall allocation. All grant applications are to be submitted through the offices of AFM locals. Check with your local on the availability of grant funding.

The MPTF reintroduced a scholarship grant program in 2020, when live performance opportunities were limited. We intend to continue providing scholarships. More details will be announced in the coming weeks.

Live music is back! And together, we can make exciting and musically diverse, admission-free community performances happen throughout North America. Let’s celebrate the sounds of summer 2022!