Studies have shown that musicians have more than three times the average risk for hearing loss. The risk of developing a music induced hearing disorder (MIHD) should be a major concern for orchestra musicians. According to Heather Malyuk, AuD, who has worked with both Chicago Lyric Opera Orchestra and National Symphony Orchestra, orchestra exposure to sound is difficult to study due to variables in repertoire and orchestra size. However, more than half of orchestra musicians surveyed have experienced MIHDs.

“These musicians are highly susceptible to MIHDs, including tinnitus (ringing in the ears), hyperacusis (sensitivity), diplacusis (detuned pitch perception), and distortion,” she says. MIHDs are more likely than modest hearing loss to affect a musician’s career, yet they are seldom discussed.

“It’s easy to forget musicians are everyday people susceptible to other causes of hearing loss such as disease, poor vascular health, sudden loss, genetics, strong medications, and lifestyle choices,” she says. “Musicians’ brains are amazing in their plasticity to adapt and adjust to changes in hearing. They are often afraid to discuss hearing for fear of losing work or negative perceptions from peers. Hopefully, that will change. If we are open and educated about these issues as a group, we can more effectively prevent them.”

Though hearing damage is often associated with louder instruments, every instrument group is at risk. “Injury is not from volume alone, but volume and length of exposure time. Practice, rehearsal, and performance create many hours of exposure,” she explains. “The US doesn’t have regulations or safety scales unique to music, but musicians can use the scales designed for industry workers to effectively protect hearing.” These scales measure noise levels in decibels (dBA).

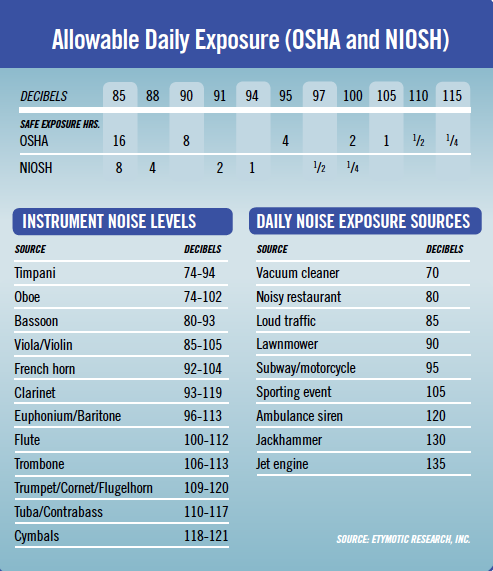

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulatory scale states that 90 dBA of sound is safe for eight hours. The safe time is halved every time the sound intensity increases by five decibels. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) scale is more stringent, starting at 85 dBA for eight hours, with the safe exposure time halved every time the sound intensity increases three decibels. (See table.) Musicians should consult with specialized audiologists to assess their risks.

Members of symphony orchestras are exposed to all kinds of noise in their daily lives, plus the sound of all the other instruments in the orchestra. (See sample noise level charts.) Adding to this is the current popularity of pop stars guest performing with orchestras. “Pops-style concerts have changed the way orchestral musicians listen and protect themselves. They are a driving factor in the pursuit of hearing wellness,” Malyuk says.

According to Malyuk, more must be done to protect orchestra musicians. “Occasionally hearing protection is provided, often in the form of foam, universal fit earplugs. Orchestras are not required to provide hearing protection, so it is a nice gesture, but often an incorrect one, as these are virtually unusable in professional orchestral environments,” she says. They are not designed for music and don’t have a flat frequency response (dampening high pitches more than low pitches), making it difficult for musicians to hear subtle nuances of music.

Other “engineering controls” are sometimes implemented to protect hearing. “Baffles can be used, but they are often expensive, tricky to deploy, and vary in terms of attenuation, depending on make and positioning. In theory, changing orchestral seating can reduce levels by a few decibels, but this affects instrumental balance for the audience,” she explains. Solutions like rotating string players and limiting louder repertoire are also not feasible in the orchestra setting.

“Giving the auditory system breaks is healthy, but it all comes down to repertoire and sound levels,” she says. “If decibel measurements can be taken on each individual player, then educated choices about breaks can be made. However, that can be costly and time consuming, and orchestras can’t conduct such a study on each piece of music.”

In-ear monitors (IEMs), when used correctly, help many musicians to hear themselves and their colleagues accurately, while also protecting hearing. “It’s possible for orchestras to use IEMs, but logistical issues stand in the way. For musicians to have personal audio mixes, extra gear is needed,” says Malyuk. “Two members of the National Symphony Orchestra have used ambient IEMs for pops performances, and I’ve fit several musicians with these devices as active variable level earplugs, used without a monitor feed. But, filtered earplugs are currently the best option for orchestral players because they are less expensive and less cumbersome.”

Some musicians are resistant to earplugs due to past experiences. “I’ve found that this is usually because they’ve been fit incorrectly,” she says. “It takes a knowledgeable, specialized audiologist to choose the best quality filter, select usable but effective attenuation, and take accurate ear impressions. Just like any area of health care, audiology has specialties.” She recommends an annual wellness visit with a specialized audiologist to check for MIHDs and hearing loss and to learn about the latest protective measures like filtered earplugs.

More often hearing protection is becoming a subject of orchestra committee discussions. “Recently, the affordability and necessity of hearing wellness programs for orchestra members has been a focus in negotiations. Education is needed in this area and that falls on the shoulders of orchestra committees, who are often underequipped for that task,” says Malyuk. This is an area where trained audiologists can assist, providing current research, cost points, and risks, as well as information regarding wellness programs and hearing protection options.

“A common arrangement I have seen within collective bargaining agreements is a reimbursement program. Musicians pay for the wellness visit and custom hearing protection costs and are reimbursed a certain, agreed upon percentage. Annual hearing wellness care is not only best for the musicians, but it also helps protect employers (such as orchestra management) from potential legal action for hearing injury,” she says. “Musicians are small muscle athletes and, as such, need annual care for their most valuable instrument—their ears.”

Heather Malyuk, AuD has spoken at ICSOM and ROPA conferences. Her clinic, Soundcheck Audiology (www.soundcheckaudiology.com), features concierge services for orchestras, supporting musicians through hearing wellness and MIHD prevention.