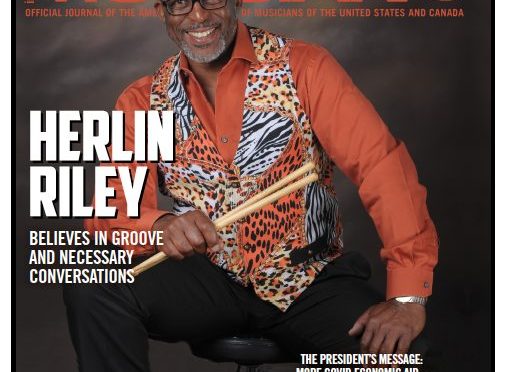

Wynton Marsalis once introduced his friend and jazz orchestra drummer Herlin Riley to an audience as, “A master of the New Orleans drum cadence, tambourine, washboard, cowbell, and many other things that can be hit and grooved upon.”

And that is certainly a fitting description. Because to Riley—who has been playing drums since he was three years old and has been a professional musician and a member of Local 174-496 (New Orleans, LA) for 45 years—playing with confidence and with intensity is all a part of being creative.

“Almost everything can be a percussion instrument; if it has a sound and has a timbre when struck, you can create music with it,” he says. “I often play a local club called Snug Harbor, and there’s a four-inch pipe that has resonance in the corner of the stage where the drums setup. I always play the pipe in my performances, and my audiences have come expecting me to hit it in my shows. I’ve been known to hit music stands, mic stands, and any other object that has a sound and is in range of my drumsticks.”

“The essence of improvisation is being creative and uninhibited,” Riley continues. “It’s the same creative and uninhibited expressions I see when I watch people of color dancing to samba, salsa, rhumba, or a Second Line groove on the streets of New Orleans. The integrity of the art form of jazz revolves around being creative, freedom of expression, and utilizing whatever objects or sounds that are available to aid in the creative process. That’s the true essence of jazz music.”

And, man, has he made some jazz music through the years.

Riley is best known as a member of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, led by Wynton Marsalis, of Local 802 (New York City) and of Marsalis’ small groups. But Riley’s story is much more than that.

He grew up in New Orleans inside a musical family. His grandfather, Frank Lastie, played drums with Louis Armstrong. Frank had three sons who were also musicians (and AFM members): Melvin (trumpet), David (saxophone), and Walter (drums), who played in a combo as well as individually with musicians such as Fats Domino, Little Richard, and King Curtis. Riley was raised mostly by his grandparents, and his uncles typically rehearsed in their house. “Whenever they rehearsed, they would roll my crib into the room and I would check out the music as an infant,” Riley says. “So that was my beginnings.”

As he grew up imbibing the music-filled air of New Orleans in general, Riley’s grandfather would show him different drumbeats, using butter knives on the kitchen table, and challenge Riley to repeat the patterns. At age 12, Riley began playing and studying trumpet—after his Uncle Melvin sent him one from New York City—and played that all through high school. He went back to the drums in college.

Were you in the Fairview?

During the early 1970s, Riley joined the Fairview Baptist Church Marching Band, which was a youth brass band run by Danny Barker, a guitarist who played with the likes of Cab Calloway and Billie Holliday. Riley credits that experience as one of the seminal moments in his musical life because it exposed him so directly to New Orleans music and culture. It was also the first time he ever met his future bandmate Wynton Marsalis.

“Wynton and I used to argue about that,” Riley says with a laugh. “He said, ‘Man, were you in the Fairview?’ And I said, ‘Yes, were you in the Fairview?’ And I said, ‘Man I never saw you there,’ and he said, ‘Man I never saw you there either.’ Ironically, someone came up with a picture of Wynton and myself playing in the trumpet section together. I must’ve been about 12 or so and Wynton was about eight or nine.”

It was actually while he was in the Fairview marching band, at age 16, that Riley joined the AFM. “My uncles encouraged me to join,” he says. “I was playing in the Fairview and playing little gigs around town, and my uncles said it would be good for me.” While Riley does not remember exactly why they said it would be a good thing to join, he does remember how quickly he learned it would be beneficial.

In the early and mid 1970s, when he was playing in New Orleans, the AFM was strong and club owners had to pay wages based on the union pay scale. But when Louisiana became a right-to-work state in 1976, many club owners started paying less, and even pitting musicians against each other in order to get jobs. “A lot of club owners were undermining musicians because the union had been diminished by the law that was passed,” Riley says. “To me, that was an important lesson: I learned that it was very strong to have the union in your corner. It gave me a basis on how to negotiate and how to be paid properly for the amount of work that you are doing, and how the union functions as one voice.”

Riley said this lesson also extended to recording work, whether for albums, movies, or television. “If you’re in our union, you know a base price that you should be paid and what you’re worth,” he says. “I think that’s vital to know, and that’s why I encourage musicians to join—because you should be paid what you’re worth.”

Years in the Ranks

Local 174-496 President Deacon John Moore lauds Riley’s continuous membership since joining the AFM at the age of 16 “under the tutelage and mentorship of a talented family of luminary musicians and music business pros, who instilled the values of unionism that he has carried with him throughout his illustrious career.” Moore calls Riley “a world-class master drummer and percussionist, comfortable and excelling in all genres of jazz,” and a musician “with a technique paramount in the artistic expression of the many facets of the roots music—gospel, blues, Latin and rhythm & blues—that tell the story of his unique heritage, having been raised in the palm of the hand of the very best people in the land where jazz began.”

Riley started playing professionally right out of high school in 1975—his first gig was in a burlesque club, playing behind the dancers and the novelty acts. He went on to play as a member of pianist and Local 802 member Ahmad Jamal’s group, and has played and recorded across the US and the world with musicians such as the late Ellis Marsalis, George Benson (Local 802), Harry Connick, Jr., (Local 802), and Wycliffe Gordon (Local 802), to name only a few. In 1988, Riley became a member of the Wynton Marsalis Quintet, and joined the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra in 1992. Riley played a large part in developing the drum parts for Wynton Marsalis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning album, Blood on the Fields, and went on to lead his own bands.

“My experience with Wynton in a big band was so unique, so important to my life because I got to play so many different styles of music playing with him,” Riley says. “I really had to hone my skills as a reader, to read and learn music quickly, so my skills became sharper.” Wynton Marsalis also pushed Riley to begin to teach drums, because the orchestra would teach kids about playing music in every city they stopped.

“I told Wynton, I don’t know how to teach because I didn’t learn in a formal way. He said, ‘Well, you play drums don’t you?’ I said yes. He said, ‘Well, tell ’em something. Just figure out what you’re doing and tell ’em something.’ So that pushed me to really think about what I was doing and get it to my students so they could understand what I was doing. And to this day I don’t teach from a book; I teach from a practical kind of setting to show them what they need to know, not just necessarily what’s in the book.”

The two main lessons he tries to teach every student are to 1) play with intensity and to 2) play with balance and control. By intensity, Riley does not mean volume, but rather playing with confidence, and a certain integrity and commitment, he says. “Learn the history and as many styles of playing the drum set as you can, so that you allow yourself to become like water (musically) and adapt to any musical environment you’re asked to perform in. It’s important to have solid understanding of the role of the drums, bass, and rhythm section as a whole. I would say all music starts with rhythm, no matter the instrument, but in order to groove, the rhythm has to be played with an intensity. … To be able to really develop a groove, that confidence is the belief in yourself, the belief in the rhythm that you’re playing.”

Lessons in Life

To have that confidence and belief in yourself also extends to life generally. As a Black man in the south, Riley has dealt with his share of racism, he says, and watching the cultural awareness coming out due to the Black Lives Matter movement has been encouraging. Doing gigs back in the ’70s, he would often be the only Black person in the club. He remembers one particular club where the owner—who was also a musician—would get drunk and tell jokes that always had a black person as the butt of the joke.

Riley, supported by his bandmates, asked the owner to stop, to which the owner would apologize and say he would, but the next night he would start drinking and telling jokes again. “So, long story short, I quit because of my pride and integrity as a Black man. This musician was very successful and affluent and probably had the highest paying gig in New Orleans for a sideman. But I just couldn’t continue under the owner’s mindset, which was ingrained in his consciousness from his childhood,” Riley says.

He sees the Black Lives Matter movement as shining a light on these injustices against Blacks that have been ongoing for decades—and it’s because everyone has a cell phone and these actions and events can be photographed and recorded in real time. Riley understands this better than most, in fact, because his nephew, also a musician, was killed by police in 2004. “They said they thought he had a gun. He had a trombone in his car, and they riddled his car with bullets because they thought he had a gun,” Riley says. “So often injustices have happened to people of color and the police, DA, judges, and the white establishments have been able to justify their unfair practices with a flat-out lie.”

Racism is an uncomfortable subject and conversation, Riley says, but it’s a necessary conversation that is needed in order to make changes. “Everybody deserves to be treated fairly and to be treated like they would like to be treated. The golden rule always applies: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. It’s a great way to live: with respect for other people.”

Herlin Riley’s Last Performance with Ellis

Riley tells the story of a concert he played with his group The New Orleans Groove Masters, comprising himself, Shannon Powell, and Jason Marsalis, of Local 174-496. They played on March 3, 2020 at the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music in New Orleans.

“Mr. [Ellis] Marsalis was in the audience along with his friend, Ms. Germaine Bazzle, who’s a singer. Ellis said, ‘Man, I want to sit in.’ Whenever Ellis Marsalis wanted to sit in with any band that I was a part of I was always honored, and the answer was always, ‘Yes, of course!’ He always invited younger musicians who were developing to sit in with him on his bandstands, including me. He played three songs with us that night: His original ‘Tell Me,’ featuring his son Jason on vibes and me on drums; he played ‘Miss Otis Regrets’ as a duo with Germaine Bazzle, his longtime friend; and ‘Tootie Ma,’ the last tune of the night. We had a great time and the audience was dancing in the aisles.

“Ellis Marsalis passed away on April 1st from the coronavirus. In hindsight, that March 3 performance was a special moment at the close of his life and career. He played with his longtime friend, his youngest son, and in the venue that bears his name and was built in his honor.”