Vertigo is a tilting, spinning sensation of being off-balance. You may feel like the world is spinning around you even when you are standing perfectly still. Vertigo symptoms are caused by a disturbance to equilibrium, and may be accompanied by nausea and headache. More than 2 million people visit their doctors each year complaining of dizziness or vertigo, and while it’s generally a harmless symptom, you can imagine how it could be debilitating and stop a performer in her tracks.

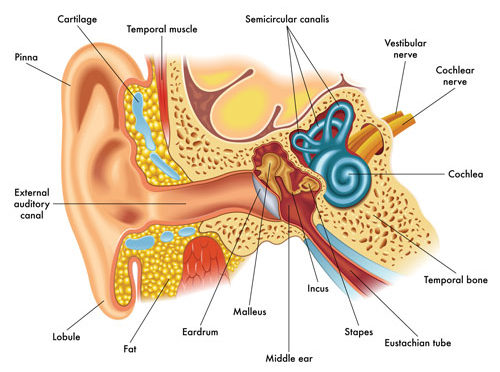

To better understand the cause of vertigo you need to look at the anatomy and function of the ear. Sound waves travel through the outer ear canal until they reach the eardrum. There, sound is turned into vibrations, which are transmitted through the inner ear via three small bones (the incus, malleus, and stapes) to the cochlea, and finally to the vestibular nerve, which carries the signal to the brain. A collection of semicircular canals (canalis) positioned at right angles to each other inside the inner ear act like a gyroscope for the body. These canals, combined with sensitive hair cells within the canals, provide us feedback regarding our position in space. When there is a disturbance in this system, it can cause vertigo.

Common Types and Causes of Vertigo

- Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): This type of vertigo is caused by tiny calcium particles (canaliths) that clump in the canals of the inner ear, which sends signals to the brain about movements relative to gravity to keep your balance. This type of vertigo is most commonly felt when tilting the head or climbing in and out of bed.

- Meniere’s disease: This inner ear disorder is thought to be caused by a buildup of fluid, which alters the pressure in the ear. Along with vertigo, symptoms can include ringing in the ear (tinnitus) and hearing loss.

- Vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis: This inner ear problem is caused by an infection (usually viral). The infection inflames the inner ear around the nerves that are important for helping the body sense its balance.

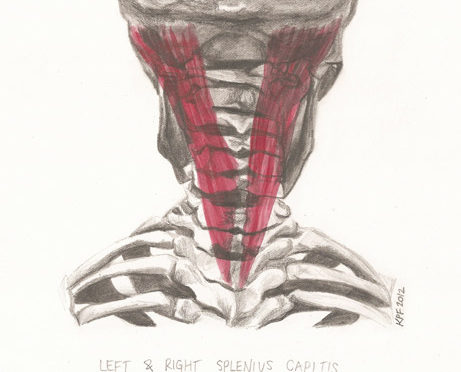

Less frequent causes of vertigo include head or neck injury, brain problems (stroke or tumor), certain medications, and migraine headaches. In many cases vertigo will go away with no treatment. When necessary, what treatment is used depends on the cause of the vertigo.

Common Treatments

- Canalith repositioning maneuvers: Performing a series of specific head and body movements can relieve the symptoms of BPPV by shifting the calcium deposits out of the ear canal and into an inner ear chamber where they can be absorbed by the body. While the movements are safe and effective, you may need a doctor or physical therapist to teach you the techniques. Also, if you are uncertain which ear is affected your doctor can let you know.

—Epley maneuver is the most common, and provides relief to 90% of BPPV sufferers.

1) Sit on the side of your bed. Turn your head 45 degrees to the side of the affected ear (not as far as your shoulder).

2) Quickly lie down on your back, with your head on the bed (still at a 45-degree angle). Place a pillow under you so it rests between your shoulders rather than under your head. Wait 30 seconds.

3) Turn your head halfway 90 degrees in the opposite direction without raising it. Wait 30 seconds.

4) Turn your head and body on its side in the same direction, so you are looking at the floor. Wait 30 seconds.

5) Sit up slowly but remain on the bed for a few minutes.

6) Repeat before going to bed each night until you’ve gone 24 hours without dizziness.

—Half somersault or Foster maneuver

1) Kneel down and look up at the ceiling for a few seconds.

2) Touch the floor with your head, tucking your chin so your head goes toward your knees. Wait about 30 seconds or until any vertigo stops.

3) Turn your head toward the affected ear. Wait 30 seconds.

4) Quickly raise your head so it’s level with your back while you’re on all fours. Keep your head at that 45-degree angle. Wait 30 seconds.

5) Quickly raise your head so its fully upright, but keep your head turned to the shoulder of the side you’re working on. Then slowly stand up.

6) Repeat this a few times for relief, resting for 15 minutes in between.

- Vestibular rehabilitation: This physical therapy may be recommended by your physician if you have recurring vertigo. It is aimed at helping to strengthen the vestibular system and its function in sending signals to the brain about head and body movements relative to gravity.

- Medication: In cases where vertigo is caused by an infection or inflammation, antibiotics or steroids may reduce swelling and cure the infection. For Meniere’s disease, diuretics may be prescribed to reduce fluid build-up pressure. In some cases, medications are taken to relieve the nausea associated with vertigo.

Occasionally vertigo can be a symptom of a more serious problem. It’s always advisable to visit your physician when you are experiencing any medical condition.