Growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, Jane Little was drawn to music from the time she was a small child, and did everything she could to seek out musical opportunities. “I so wanted to play the piano,” she says in her Southern drawl. “But my family struggled during the Depression and we had no piano. I would go to the neighbors’ house to use theirs. I would try to pick out tunes and taught myself to play a little bit.”

Little tuned in to the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts every Saturday afternoon, joined the glee club in junior high, and decided that she would become an opera singer. “I was delusional at that time!” she laughs. There was no doubt, though, that music was her passion. Atlanta didn’t yet have its own symphony, but when an orchestra toured to the city, Little was eager to attend. “It was the first time I heard a symphony orchestra perform live,” she recalls. “And I was just carried away.”

Facing the Bass

Little continued to sing and planned to join the high school glee club when she entered her freshman year. But the orchestra director had different plans once she saw the results of Little’s music aptitude test, which every incoming student was required to take.

“I was called to the music room, and the orchestra director asked what instrument I played,” remembers Little, who answered that she didn’t play an instrument, but liked to sing. The director was shocked and explained that Little had scored tremendously high on the test. “I was 14 at the time, which is a little late to start an instrument, but she asked how I would like to be an orchestra musician. I said that I would like it more than anything!”

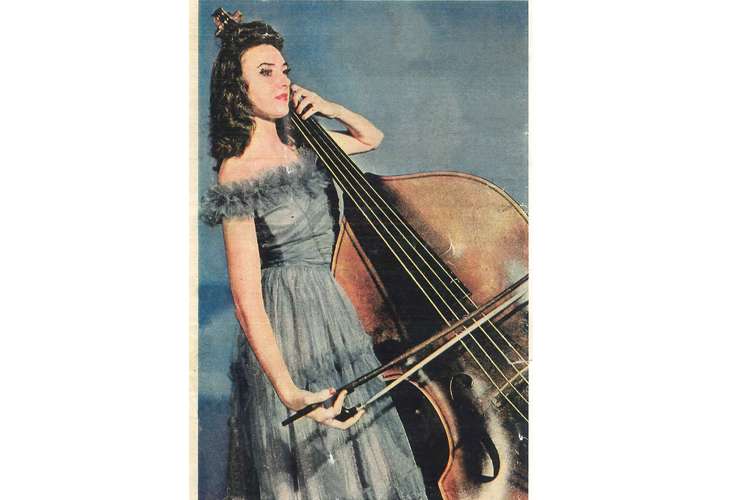

The orchestra was in short supply of bass players. At five feet and three inches, and weighing less than 100 pounds, Little seemed an unlikely match for the massive instrument, but she wanted to try. She struggled at first to hear the lowest pitches and could barely press down the thick E string—not to mention, even just carrying the bass around was no easy task.

“I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, this is going to be a challenge!’” she says. “But I was back for the next lesson, and the next, and the next.” After just a couple months of private lessons, Little was ready to join the orchestra—and not only did she join, but she was quickly appointed principal bass.

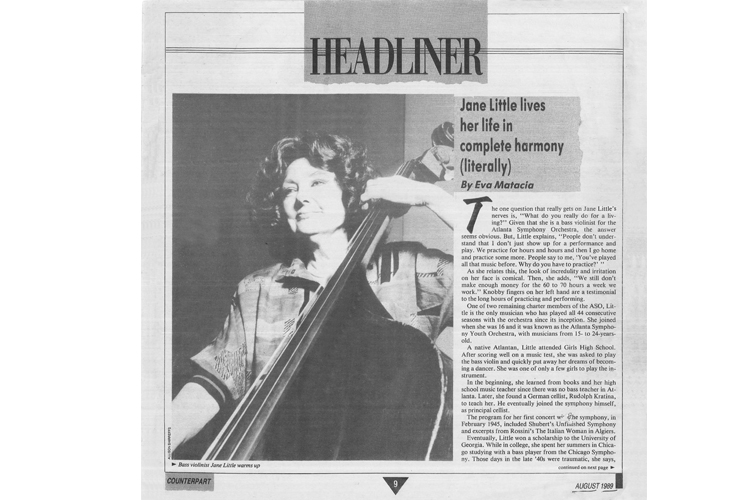

The next year, the Atlanta Youth Symphony Orchestra was formed under the direction of Henry Sopkin, a well-known youth orchestra conductor in Chicago. Little became a member of the symphony, which performed its first concert on February 4, 1945. In retrospect, that was the beginning of her 70-plus-year career with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra (ASO); within three years, Sopkin transformed the youth symphony into the orchestra now known as the ASO.

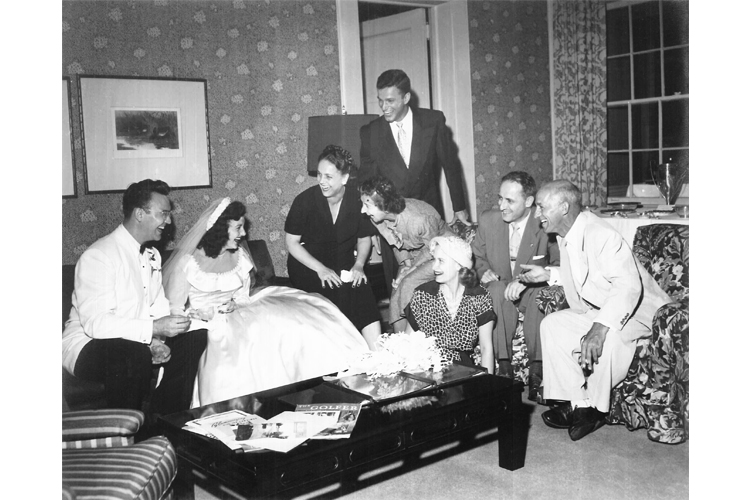

Eventually, Little met someone who happened to be able to give her a hand carrying her bass. Warren, who would become her husband, joined the orchestra’s flute section in 1948. The two had first met at the University of Georgia, but Little was engaged to a naval officer at the time. She returned to ASO after spending a summer in Chicago studying with a great bass teacher from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Warren noticed that Little was no longer wearing her engagement ring; she had broken her engagement in order to stay in Atlanta and continue playing with the orchestra. Warren asked her out right away. Their first date was a performance by the legendary violinist David Oistrakh.

“I must say that when I met Warren, I was very impressed that he played a small instrument, so he could carry my bass around!” jokes Little. The couple made music together in the ASO until Warren’s retirement in 1992.

Acing the Audition

Henry Sopkin led ASO for 21 years, increasing the budget, adding concerts, and introducing education initiatives. When he stepped down in 1966, it was announced that Robert Shaw—an exceptional choral conductor who had been working with George Szell in Cleveland—would become the next ASO music director. Little knew that even more changes would be ahead for the orchestra. She was excited, but nervous.

Shaw asked to hear every member of the orchestra play individually. Little had two weeks’ notice about the audition, and she didn’t waste a minute getting to work; she knew how crucial this could be. “I told my family that Christmas would have to be on hold that year,” she says. “I was practicing seven or eight hours a day, going through all the literature, doing everything I could.”

When she walked into the audition, Little felt immediately at ease with Shaw. She aced her audition: “I never played better in my life!” she exclaims. “When I got my contract, I was overwhelmed. Robert Shaw had appointed me co-principal of the bass section.” Little was later named assistant principal bass, and now holds emeritus status for that position.

Under Shaw’s watch, the ASO continued to build its reputation. Little can list off an impressive roster of guest soloists and conductors she has performed with—Nathan Milstein, Isaac Stern, Benny Goodman, Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland, and many more.

One of her favorite memories is of a sold-out concert with pianist Arthur Rubinstein, who was playing the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto. “He plays the first big chords of the concerto, and all of a sudden, the piano starts rolling toward the end of the stage,” she recalls. “The people in the first rows were scattering. Everyone was just in horror!” Thankfully, the piano caught in the footlights, which kept it from crashing off the stage, and Rubenstein took it all in stride. Once the piano had been secured, the show went on.

The show went on for Little, too, as ASO became a full-time orchestra and gained international renown. She played under Yoel Levi, who became music director in 1988 and “brought the orchestra to new heights,” Little says. He was followed by Robert Spano of Local 148-462 (Atlanta, GA), who took over in 2000. “Through two major lockouts in the last four years, Spano has remained a friend and supporter to the musicians,” she says. “He was determined to maintain the orchestra’s status as a major symphony.”

Earlier in her career, piecing together a living was a bit more unpredictable. “Back then, when the orchestra was still part-time, you would go and beat the bushes for work,” she says. For 15 years, Little played with Theater of the Stars, where she was the only woman in the band. She taught private bass lessons and even saw one of her students grow up to join the ASO.

She’s played for opera companies, and remembers times when she was the only bass player in the pit, and had her instrument amped. She also played with the Savannah Philharmonic Orchestra, often making the four-hour drive with a group of fellow ASO musicians late at night after an ASO concert or rehearsal, in order to be ready for a rehearsal in Savannah the next morning. “You did what you had to do,” she states matter-of-factly.

Chasing the Record

Little, who belongs to Local 148-462, is grateful to the AFM, as well as the International Conference of Symphony Orchestra Musicians (ICSOM), formed in 1962, for improving working conditions for orchestra musicians. She has witnessed the positive changes to audition procedures, tenure, and the musicians’ ability to weather strikes and lockouts.

Little has done her share of walking the picket lines and remembers her husband’s determination to negotiate fair contracts—even if it meant late-night phone calls and meetings—when he served as president of the local. “It’s great protection to be a member of the AFM—the union is your friend!” she says. “It brings greater stability to our careers.”

Little has now completed her 70th season with ASO, setting the record as the orchestral musician with the longest-running career, despite enduring several injuries and challenges over the years. At a certain point, she explains, she knew that she had to keep playing because she was so close to that goal. “To be absolutely sure [that I break the record], I’m going to play into my 71st season,” she says, adding that she might consider retirement at some point during the season.

Of course, more important than any record is the unique dedication that she shows for her instrument and for symphonic music. Even over a seven-decade career, she continues to give her all at every concert, never resting on her laurels. She was recently preparing for an ASO concert that included Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony and noted that it was one of the first pieces she played with her high school orchestra. “It’s still difficult!” she says, a testament to the fact that she always reaches to grow in her artistry.

“Suppose I had been absent the day that we took that music test?” Little wonders. “I probably wouldn’t have this career. I must say I’ve had a charmed life.”