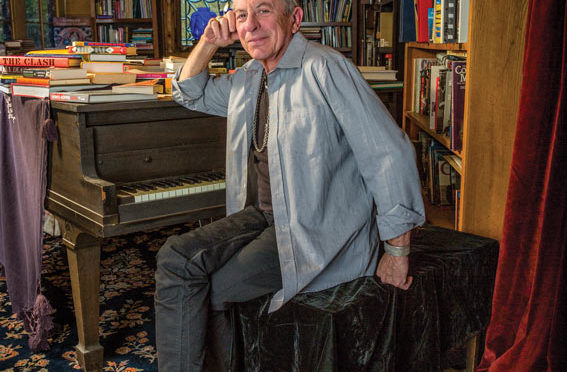

Writer, musician, and longtime Local 433 (Austin, TX) musician Joe Ely says the solidarity and protections of the AFM are important to him. He’s been inducted into the Texas Songwriters Hall of Fame, was named 2016 Texas State Musician, and most recently was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters.

Joe Ely of Local 433 (Austin, TX) was recently inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters, which he says came as a shock, something he never saw coming. But it’s storytelling, after all, and no one tells a story like Ely. He’s been writing songs since he was a kid growing up in Amarillo, and later, in Lubbock. Ely says, “I was always listening to things, background noise, the wind blowing a branch against a screen window.”

Ely has kept journals for years and often sketches to have a visual. He recalls Tom T. Hall once telling him, “Some people can travel all around the world and not see a single thing, others can travel around the block and see the whole world.” “That made me continue to keep writing down observations and eventually building them into a form,” says Ely. The University of Texas eventually published some of the journals as raw material titled Bonfire of Roadmaps.

As a songwriter turned novelist, it was difficult for Ely not to keep the words to a minimum. “Instead of a line in a song, it’d have to be three pages in a book. It was the first thing I had to overcome,” he says. Like Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy—of whom Ely is a fan—he draws on the landscape to deliver the emotional depth of his characters. In his autobiographical novel, Reverb (2014), he writes of Lubbock in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s a gritty world, but Ely digs into the story of young working-class men, usually in trouble, driving barren roads, living with the threat of going to war.

It’s easy to imagine the narrative running through his life. Ely left home at 16, went to Fort Worth and joined a band. From there, he went to Houston and Los Angeles. “My daddy died a few years before that and I was not doing good in school. I just didn’t see any future in Lubbock. I was playing in bands. I was kind of the sole breadwinner in the family. I’d play till midnight or one in the morning and try to go to school the next day. After school, I washed dishes at an old fried chicken place. I didn’t see an end,” he says.

In the mid-1960s Ely would periodically return to Texas to appear before the draft board, which at the time, he remembers, was drafting about 50,000 kids a month. “I’d always come back and regroup and go somewhere else, from one coast to the other,” he says. In New York City, he ended up joining a theater troupe and going to Europe. “That’s how I started traveling and collecting songs, during that era.”

In the summer of 1971, back in Lubbock, Ely teamed up with friends Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore to form the country-folk group, The Flatlanders. The band toured extensively, headlining small shows and opening for bigger acts. Among these, remarkably, was the punk rock group The Clash. (In fact, Joe Strummer was supposed to record with Ely’s band, but died before it happened—one of Ely’s greatest disappointments.)

Such offbeat arrangements are not unusual for Ely, who once made a record with German opera conductor Eberhard Schoener. Ely says, “He had the first Moog synthesizer, which he bought from John Lennon—who hated it. We worked with that synthesizer and two acoustic guitars and did an experimental piece. A couple of years later, I bought an Apple computer and started working on songs as an experiment. He kind of inspired me.”

Ely has always been something of an artistic maverick, seamlessly moving between country music and rock and roll. In the 1970s and 1980s, especially, he championed the progressive country scene in Austin. “At a young age, I discovered Woodie Guthrie, who lived in Amarillo for a good part of his life. In my teenage years and early 20s, I just happened to run across some of the songwriters who would influence me for the rest of my life,” he says.

Ely has played with mandolinist Chris Thile of Local 257 (Nashville, TN) on A Prairie Home Companion and with Bruce Springsteen of Locals 47 (Los Angeles, CA) and 399 (Asbury Park, NJ), James McMurtry, The Chieftains, Tom Petty of Local 47, and John Mellencamp. With Guy Clarke, Lyle Lovett of Local 257, and John Hiatt he formed a group that played 40-50 shows a year for about 20 years. “We’d go all over the states, a different city every day. We’d all sit on stage together in a guitar pull, where one person does a song and passes it on to the next.”

On his albums, Ely likes to incorporate cover songs, especially ones he feels have not gotten their due. When he was working on Letter to Laredo, he was just about finished with the record when he went to Europe for a few gigs. “I was in a bar in Norway and heard a song on the jukebox about a guy who crossed over into the US with a fighting rooster and went up and down the coast of Texas and California trying to win enough money to buy back the land that Pancho Villa stole from his family,” he says, explaining that the song eventually made its way onto the album.

A member of the AFM since 1972—when the first Flatlanders’ record came out in Nashville—Ely says the union is an important part of being able to make a living, especially as a traveling musician. That solidarity informs his work. The Flatlanders song, “Borderless Love,” (2009) about the fence on the US-Mexico border, is even more relevant amid today’s political tumult so the band has reintroduced it to live sets.

“I think you take from what’s been and give to what will be,” says Ely, who now lives in Austin and works with a number of young musicians there. Just after the 2015 release of the more literary and deeply personal Panhandle Rambler, he was inducted into the Texas Songwriters Hall of Fame and was named the 2016 Texas State Musician, an honor previously bestowed on Willie Nelson of Local 433 and Lyle Lovett.

Along with 25 albums to his credit, the 70-year-old Ely has about five books of poetry written, which he hopes to compile into a single collection. He’s led symposiums for Texas Tech University; he recently conducted a solo acoustic tour in the Midwest; and for the next couple of months, he will tour Texas and California. “I like to mix it up. Playing with a band full time can be restrictive. You’re always herding people. I prefer to go out, me and the guitar and a bag of stories.”