On October 27, the Big Apple Circus made its return to Lincoln Center, just in time to celebrate its 40th anniversary. Created by former European street performers Paul Binder and Michael Christensen, Big Apple Circus debuted in New York City’s Battery Park in 1977, relocating to Lincoln Center in 1981. Over the years, it became a New York City holiday season staple. However, unable to recover from the 2008 recession, the nonprofit, one-ring circus filed for bankruptcy in 2016.

Last February, Big Top Works purchased Big Apple Circus and set to work restoring the beloved show and returning its performers to work.

Local 802 (New York City) Business Representative Marisa Friedman is in charge of the AFM contract covering the Big Apple Circus musicians. “Our main concern was that the circus would continue to use live music and that the musicians who worked for the old circus would continue to work for this new one,” she says. “Negotiations went very well. It was clear that the circus valued live music and wanted to make a fair deal with Local 802.” In the end, the union negotiated an improved three-year agreement for the musicians.

According to Big Apple Circus Conductor Rob Slowik of Local 802 (New York City), the show’s band has eight permanent musicians. “Everybody who is on the new primary hiring list has played with the circus before, but a few of the former musicians moved out of state and are doing gigs in other parts of the country,” he says.

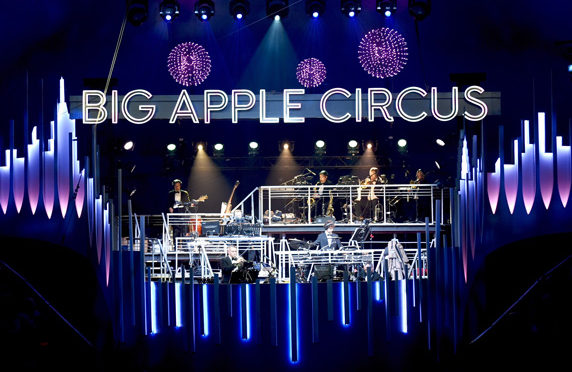

The Big Apple Circus band (L to R) back row: Wages Argott, Jacob Levitin, Jeff Barone, Brian Killeen, Patrick Firth, and Michael Bellusci; middle row Neil Johnson and Jim Lutz; in front, Conductor Rob Slowik.

“We essentially just made modifications to the old agreement. We expanded the scope of the recognition agreement to cover more work, added health and safety protections, and also included payment for promotional use of recorded material,” explains Friedman. “The musicians will receive increases in wages and health benefits—something they have not had in several years due to the circus’s financial problems.”

Among new band members is Local 802 and 256-733 (Birmingham, AL) member Wages Argott, a trumpet player who was the bandleader for the Ringling Blue show that closed earlier this year. Slowik brought him on as associate conductor. “It’s nice that I have a sub who has already conducted thousands of circuses,” says Slowik, also a trumpet player. A couple other former Ringling musicians are on the sub list for this year.

“Each year brings a new Big Apple Circus show, with a new cast and new music, but the same band,” explains Slowik. “We change the instrumentation depending on the show theme, but we always use our hiring list. Once a musician plays with us and is on the contract, they have the right to first refusal, if we use their instrument again.”

The musicians of the Big Apple Circus band have returned to their bandstand with an improved three-year AFM contract negotiated by Local 802 (New York City).

The circus’s 2017 theme focuses on its 40th anniversary. “The set looks like the skyline of New York City and the music draws from all the different contemporary musical styles represented here—pop, rock, jazz, Latin, classical,” says Slowik. “It’s not music you would normally associate with a circus.”

Among performers headlining the new show are world record holder Nik Wallenda and the Fabulous Wallendas, trapeze artist Ammed Tuniziani of the Flying Tunizianis, as well as Grandma the Clown, who has returned from retirement.

When it comes to music selection for the various acts, Slowik says that the producer makes the final decision, but there is input from the director, as well as the performing act. “We try to honor the act’s needs in terms of tempo and timing, and we like to use music that is going to inspire,” he says. “While there is often some initial resistance to new music from acts who may have used the same music for 10 or 15 years, at the end of the season, they frequently want to buy the music and take it with them.”

Use of a click track helps the band keep to a steady tempo for performances, and Slowik keeps a constant eye on the show for split second adjustments. “We have a lot of vamps built into the music but often we’ll have to create new vamps on the fly,” he says. “Something can go wrong at any point, whether it’s somebody missing a trick, wanting to repeat a trick, or something that goes wrong with the rigging or a prop.”

“I try to get the dogs to count the downbeat of the bar but they don’t listen, and neither do the horses,” laughs Slowik. “One of the nice things about having a band with a lot of circus experience is that they can almost read my mind.”

Musicians new to the circus, even veteran Broadway players, require some training. “They have to come watch the show. I give them a video of me conducting and a pdf of the book. One of the things I tell them is: ‘This vamp is four bars, but the cue could come anywhere, including in the middle of the bar.’ On Broadway, if you have a two-bar or four-bar vamp, it is almost always at the end of four bars. It can take people a while to get used to that. You really have to be aware because the cue could come out of nowhere.”

On occasion, Slowik says he has even become a part of the act. He recalls a skit he did with Grandma the Clown where he was hoisted 30-feet up in the air to play his trumpet. “It was a lot of fun!” he says, adding that he looks forward to something like that happening in the future.

The new Big Apple Circus show premiered October 27 and runs through January 7. After that, it will begin an East Coast tour with stops between Atlanta and Boston. When on tour, the Big Apple Circus travels with about 50% of its core band, hiring local AFM musicians in whatever city it visits.