The scene opens on a black screen. From the depths of inaudibility, a single eerie string chord rises to underpin the image of a windswept desert landscape.

The scene opens on a black screen. From the depths of inaudibility, a single eerie string chord rises to underpin the image of a windswept desert landscape.

Instantly, we know where we are: a desert planet much like the homeworld of Luke Skywalker. And, equally importantly, we know who wrote that unmistakable chord: John Williams, the legendary composer of the soundtracks for all six (soon to be seven) installments of the Star Wars saga.

It’s probably fair to say that a significant portion of the American public was waiting impatiently for the debut of this first of two trailers advertising the Christmas release of The Force Awakens, the latest Star Wars chapter. It’s an equally fair bet that Williams’ music played a big role in that anticipation. Every bit as important as the characters and scenes they portray, Williams’ soundtracks have tended to take on a life of their own in every film he has scored in a career spanning more than six decades, and incorporating a filmography fast approaching the century mark.

With the film’s premiere still months away, recording sessions for The Force Awakens are just getting started, with the initial sessions slated for the first week of June. Williams tackled earlier recordings for both trailers, with the second trailer being released several weeks ago to add to the mounting excitement around Star Wars VII. Williams says sessions will continue through August, possibly into September. “Then it’s back and forth with editing,” he says. The music will be recorded over several months while working in tandem with the film’s editorial and special effects teams on the West Coast. “At the moment I’m working on composing the music, which I started at the beginning of the year. I’ve been through most of the film reels, working on a daily basis.”

Old School Approach

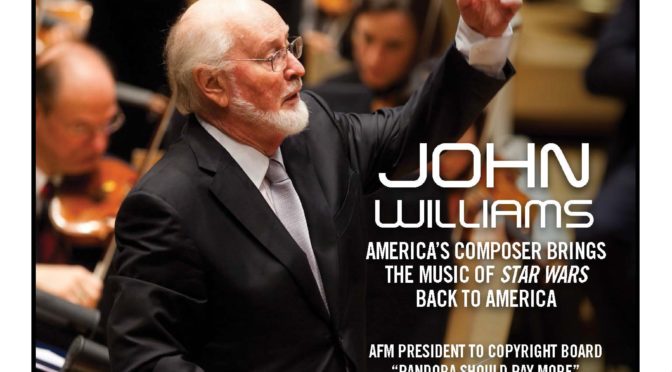

John Williams, a life member of Locals 9-535 (Boston, MA) and 47 (Los Angeles), is the winner of five Academy Awards, four Golden Globes, and 22 Grammys, and has composed many of the most popular and recognizable film scores in cinematic history. He meticulously crafts themes that virtually become living, breathing characters in their own right. But it may come as a surprise that the man who writes music for space pirates and evil galactic empires prefers a fairly old-fashioned method of composition. “I work very much in what some would consider old school,” he says, “in front of the keyboard with pencil and paper. The piano is my favorite tool. Over the decades there has been so much amazing technological change in the music business, but I’ve been so busy that I never really retooled.”

Williams explains that it used to be standard practice for a film composer to write music that was then passed off to assistants to flesh out for full orchestra. By contrast, he typically composes fully orchestrated sketches, eight to 10 lines indicating winds, brass, strings, and percussion. “The music library then transfers these directly to a computerized score from which instrumental parts are made,” he says. “We can reprint parts, edit as needed, change the bowings, etc.” He admits the irony is not lost on him that his work quickly becomes state of the art despite its more traditional beginnings.

Somewhat surprisingly, Williams prefers not to read scripts before he tackles writing his first ideas on a score. “I’ve always preferred to write only to footage,” he says. A little like a set designer, he writes music according to a story’s mood and setting, and the feeling that a particular scene might be trying to convey. The process starts with a “spotting” session, deciding in meetings with the director which scenes will feature music and which will not. For four decades, Williams has enjoyed a fruitful (to say the least) collaboration with director Steven Spielberg, and—for most of the previous Star Wars films—George Lucas as director and/or screenwriter. For The Force Awakens, Star Wars newcomer J.J. Abrams is in the director’s chair.

“J.J. Abrams has been a joy,” says Williams, expressing his delight with the working relationship so far. “He’s a very genial, warm person. We had a few preliminary meetings and I played themes on the piano to which he responded very positively. By and large he has allowed me to do my thing, and our minds have been together on our approach to the scoring.”

Once Abrams has the music in hand, the film will be edited. “Neither of us will see the final version with the special effects until much later,” Williams continues. “Any music changes that need to be done are made later in the editing process, which sometimes involves some rerecording.” Every shot requires thousands of adjustments. “It’s a two-hour-plus journey of complex details that all interrelate, with music being only one of them,” he adds. Tempo, dynamics, instrumental effects—all need to be married to what is happening in the screen images. Williams feels that when the desired effect is achieved, all those long hours of work should be unseen and unnoticed. “The final product, the finished film, has to feel seamless and natural, as with everything we do. Time is just one of the necessary ingredients in the process.”

Music as Character

Film music’s traditional role has been to set a mood, but remain subservient to the screen action. In many cases, this role also included the subtle underpinning of a particular character to reinforce personality traits—or quirks. In the case of the Star Wars films, Williams has aimed to raise the music to the level of a story character in its own right. As with his approach to composing, the technique used to achieve this goal looks back to an earlier time: that of 19th century opera composer Richard Wagner and his concept of the leitmotif, a recurring theme throughout the opera that becomes associated with a particular person, idea, or situation.

Film music’s traditional role has been to set a mood, but remain subservient to the screen action. In many cases, this role also included the subtle underpinning of a particular character to reinforce personality traits—or quirks. In the case of the Star Wars films, Williams has aimed to raise the music to the level of a story character in its own right. As with his approach to composing, the technique used to achieve this goal looks back to an earlier time: that of 19th century opera composer Richard Wagner and his concept of the leitmotif, a recurring theme throughout the opera that becomes associated with a particular person, idea, or situation.

Wagner’s four Ring operas, not unlike the Star Wars saga, are massive in scope and reach, with literally dozens of characters that need to be remembered and differentiated. Each character (and sometimes a nonliving story element) is given its own particular identifying theme, the leitmotif. In four operas lasting up to six hours each, Wagner utilized more than 90 of these themes to tie together story and characters. Thus it is with the galaxy-spanning Star Wars films, where from the outset Williams linked Darth Vader inexorably to a dark, unstoppable march, while Princess Leia’s regal beauty is given voice by solo flute and horn. Even the Force, the unseen mystical power binding together the Star Wars galaxy, is given its own special snippet of music. Over the course of the next five films, most of the regular Star Wars characters come to be immediately identified by the particular themes that Williams has created for them.

Williams says he plans to continue the use of leitmotifs in the new film. “While the majority of the music is also new, there are necessary references to early story lines, which helps create association with the previous films,” he explains. “So the music will look back in spots to the earlier films, but there are also new themes that will be applied in a similar way.”

So it would seem that even though film composition has changed radically in the last half-century, there are some techniques that will always find a use. This blending of old and new is something of a recurring theme with Williams, and that includes where he sees film music heading in succeeding generations. In the ’40s and ’50s, serious composers routinely wrote film music. While this isn’t the case so much these days, he sees the next generation of composers returning to it. “Philip Glass, for example, has been quite involved in writing film music, and this has helped get other composers more interested in the possibilities in writing for film,” he points out. “In the future, I think serious composers will become even more interested. Changes in technology also help change aesthetic approaches. More connections between the audio and visual world also open up possibilities that young composers find increasingly intriguing.”

First Class Musicians

A living, breathing score takes talented musicians to bring it to life. After six previous film soundtracks being recorded in the UK with the London Symphony Orchestra, The Force Awakens marks the first Star Wars soundtrack to be recorded on American shores, utilizing musicians from AFM Local 47. “With this new film, the schedule has evolved to the point that I’ll need to be working with the orchestra continuously for several months, and that’s obviously easier for me to do here in Los Angeles, than it would be in London.”

A living, breathing score takes talented musicians to bring it to life. After six previous film soundtracks being recorded in the UK with the London Symphony Orchestra, The Force Awakens marks the first Star Wars soundtrack to be recorded on American shores, utilizing musicians from AFM Local 47. “With this new film, the schedule has evolved to the point that I’ll need to be working with the orchestra continuously for several months, and that’s obviously easier for me to do here in Los Angeles, than it would be in London.”

“We are thrilled that this is the first Star Wars soundtrack to be recorded in the US,” says Sandy DeCrescent, who has contracted Local 47 musicians for Williams’ film scores for many decades. “So much music before this was disappearing overseas, and John has been a moving force in bringing the work back to American musicians.”

Williams says he feels very privileged to be working with the freelance orchestra in Los Angeles, an ensemble he knows well. “This group is made up of a pool of freelancers in Southern California. I’ve worked with them for decades now on a variety of films, and I am friends with most of them. They consistently come together to form a fabulous orchestra, and I’m always happy and proud to be reunited with them for these projects.”

Trumpet player Jon Lewis is a member of the freelance orchestra, and he says the experience is off to an incredible start with the recording of the two trailers. “The first trailer was the first time any of this music was recorded in LA,” says Lewis. “We had the pleasure of running the original Star Wars main titles for a ‘warm-up,’ as John called it. What a thrill that was, and it was such an amazing sound to hear coming out of the Sony scoring stage that day—as near perfection as I’ve ever heard.”

Stephen Erdody, Williams’ principal cellist for the last 16 years, agrees, adding that the working process with Wiliams is always efficient and rewarding. “John is an outstanding musician, an amazing orchestrator, and he has the best ears in the business,” Erdody enthuses. “The two trailer sessions were each three hours long, and all of us take great pride in our speed of recording and our ability to adjust and make changes to improve the final product as quickly as possible.”

“The pressure to get things right is always there in any recording session, and I think the Los Angeles musicians meet that challenge better than anywhere else in the world,” explains Lewis. Aside from small changes or balancing adjustments, each and every take is as presentable as the next.”

“When that red light goes on, it’s 100% focus and attention to producing an amazing performance,” adds horn player Andrew Bain.

For flutist Heather Clark, the experience of working with Williams has an added element of pressure. “The amazing flutist Louise DiTullio has played principal flute for John Williams the past 40 years, and it’s an honor and a great responsibility to fill such big shoes on a huge movie playing for a legendary composer who continues to raise the bar on film music. It will be the experience of a lifetime.”

All four musicians agree that the thrill of being part of an American cultural icon far outweighs any pressures and stresses of recording sessions. Says Erdody, “A few days after I graduated from Juilliard in 1977, I saw Star Wars and it changed the way I watched and listened to movies from that day forward. That score had an enormous impact on me, and I can’t believe some 38 years later I will be a part of the next installment.”

“I’m still so in love with this business, and to be the first American orchestra to play for a Star Wars movie is beyond exciting for all of us,” says Lewis. “I think the entire movie industry underwent a major shift due to the grand score that John Williams composed for the original movie. The trend of movie music shifted back to full orchestras, and for several decades since, the role of music in film has been far more important than ever before.”

As Williams loves his LA musicians, he has similar high praise for orchestra musicians elsewhere across the US. Over the past two decades since his 13 years at the helm of the Boston Pops, he says he has conducted as many American orchestras as he could possibly manage with his schedule. In particular, Williams feels a responsibility to be involved in benefits for AFM musicians’ pension funds and also for educational outreach programs. “We have so many orchestras in this country that are truly world class,” he says. “All of them are fabulous. It makes me realize that, although our country is geographically larger than most, we really do have more amazing orchestras than any other place.” He believes this speaks to the success of American music education. “We can all take great pride as a nation in the number of fabulously high-level arts institutions in this country, and we don’t praise them nearly enough,” he says.

“There are obviously great orchestras and schools all around the world, but we can be so very proud of what American schools produce here every single year. We don’t celebrate this enough, and we absolutely need to be more vocal about it.”