I don’t need to remind a musician how important resonance is. As a latecomer to music, I first grasped the importance of resonance in my high school physics class when we watched the famous video of the collapse of the Tacoma-Narrows bridge. Hitting the bridge at just the right frequency, the massive undulations eventually caused it to collapse. I paid homage to the site as a naturopathic medical student when I moved to Washington years later.

After graduation, I started a Tai Chi class to attract more patients and I stumbled across a delightful practice called “The Six Healing Sounds,” which first appeared in an ancient Chinese medical text from the fifth century. Tao Hongjing, the author, explained that “one has only one way for inhalation, but six for exhalation”—referring to the idea in Chinese medicine that there are six specific sounds that create a resonance with six very important internal organs. In large part, these organs correspond with different natural elements through something called the “doctrine of systematic correspondences.”

For example, the liver in Chinese medicine is the organ that relates to the wood element. In addition, it governs tendons, and relates to the sense of sight. So a Chinese doctor may interpret laxity in the ligaments as a problem originating in the liver. Similarly, staying up into the late hours of the evening, staring at a telephone screen, can burn up an important fluid of lubrication, called Liver Yin, by virtue of the eyes’ connection to the liver.

Each organ also has a related emotion that, when repressed, or given too much free reign, can injure the organ. The relationship is a two-way street, however, and when the organ is working properly, it can regulate emotions in beneficial ways. Each organ has a passion, which is kind of a warped, ugly spawn of that organ’s virtue. The liver’s passion is anger, whereas its virtue is kindness. Anger and kindness, according to the Six Healing Sounds, share a common vibrational energy; they both relate to sensitivity. Anger is often an inwardly focused sensitivity, the slightest offence can send an angry person into a rage. Kindness, the liver’s virtue, is a more outwardly focused sensitivity.

Tao Hongjing believed that it is natural and healthy to respond to another’s pain or complaint with a desire and commitment to help. Just think of a time when someone was patient, sensitive, and understanding to one of your complaints; it probably did a great deal more to help you get through your rough patch than had the person responded in protest. But there is an added piece of good news: If you are feeling the passion, this is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, feeling anger is a vehicle that can more easily be steered towards kindness than something that is just parked and stationary in the driveway.

The Qi Gong practice of the Six Healing Sounds is meant to help you steer your emotions to healthier places. I’ve often compared it to the idea of choir singing. The medical literature abounds with papers about how singing improves resiliency, sleep, and a whole host of issues. So let us practice this musical Tai Chi/ Qi Gong exercise, rejoicing in its benefits to our health.

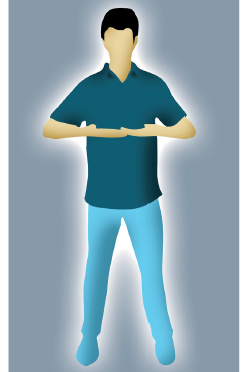

To start this routine, stand with your feet about shoulder width apart, with a slight bend in your knees. Your hips are centered over your ankles, and your shoulders over your hips. Place your hands on top of your liver. As you breathe in and out, visualize the right and left lobes of your liver. Let come to your mind something that has made you angry. Perhaps it’s someone you know. Now try and separate that thing this person did that made you angry from that person themselves. See that person without the thing they did to make you angry. Now just let go of that thing they did to make you angry.

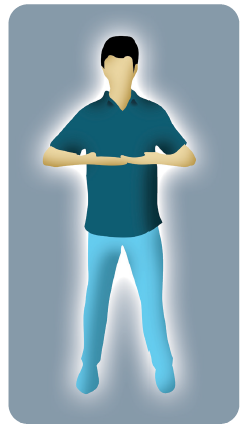

At this point, interlock your fingers and bring your hands high up above your head, with your palms facing skywards. Bend to your left side, giving your liver a good stretch. Take a deep breath in, open your eyes open wide, and sing out loudly the sound, “噓 xū” which is pronounced like the word “shoe,” just like the one you are wearing on your foot. “Shoooooooooooee.” Let that last vowel sound really vibrate, shaking all the anger out of the liver. Relax your hands on your thighs, and as you breath in, envision a green light enveloping you. Breath out again, surrendering your anger to the Earth, and believing, as you breathe back in, that She can give it back to you in the form of kindness.