Classical Harpist Treads New Paths Playing Tango

Anna Maria Mendieta has no trouble recalling the dayspring of her lifelong love affair with the harp. At age five, her arts-loving parents (her mother was a pianist and accordionist; her father played classical guitar and saxophone) played a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, and the overture swept her away.

“They told me the story of Romeo and Juliet and I remember being so amazed because you can really hear it in that music, and there’s this moment where everything becomes silent and all you hear is this beautiful harp. And that’s when I knew: That’s what I want to play,” she says. “I sat there with my ear right up to the speaker and I had them play the recording for me over and over again.”

Unlike Shakespeare’s infamous star-crossed lovers, Mendieta’s love was requited not too much later. Her parents started her on the piano while they figured out the logistics of harp studies and found her a teacher. “My father was a great collector of instruments. He had all sorts of things, even a harpsichord! But no harp,” she says. By age seven, she had begun studying the Salzedo method with Israeli harpist Efrat Laury-Zaklad at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. “I took my first lesson and I knew; clearly, there was never any wavering from that.”

The towering physicality and visual beauty of the harp—and the highly-aesthetic Salzedo method in particular—have always been part of the appeal for Mendieta. The visual sleight-of-hand that keeps the audience’s eyes on the graceful gestures of the arm and away from the foot pedaling action that determines the harp’s key is a dance in itself. (“Now you know the secret to the long gown,” she slyly whispers.) For her, the connection with dancing offers a certain familiar comfort: alongside their musical studies, Mendieta’s parents encouraged their children to study dance. The family’s Spanish heritage made flamenco an important point of cultural connection (one of her sisters is a professional flamenco dancer), but it was after Mendieta’s career as a professional harpist was well-established that she found a new love: the tango.

Like so many people, Mendieta found the tango through the compositions and performances of revolutionary Argentinian composer and virtuoso bandoneon player Astor Piazzolla, whose nuevo tango style changed the face of both classical music and tango. Falling in love with the music and its accompanying dance, Mendieta sought out harp arrangements of Piazzolla’s work. Finding none, she wrote directly to Pablo Ziegler, Piazzolla’s former pianist and the preeminent composer and performer of nuevo tango, to see if he had anything that might work. No luck. “I said, ‘Just send me what you have and I’ll figure out how to play it,’” she says.

“People told me it wouldn’t work, there was just no way. ‘You can’t play tango music on a harp, it’s too chromatic,’ they said. And it was a real challenge,” Mendieta recalls. “Astor Piazzolla’s music is so incredible. He uses his instruments not only as melodic instruments but as rhythm instruments. It took me many, many years to figure out how to do that on the harp. I had to change my technique in order to get the sounds. To play the chromatics, I figured out different ways to bend the notes.”

Mendieta realized that the methods used by jazz harpists to use the pedals of the harp strategically to create slides and slurs could provide a basis for this new technique. This, of course, went against everything she had ever learned about the pedals: be as gentle and quiet as possible so as not to lose the clarity of notes; move feet with subtlety so as not to distract from the hands. Suddenly, she found herself using the pedals like a pedal steel guitar player would: bending her notes in real time while also getting creative with enharmonics, using them to substitute for chromatics when an extra note was needed without a pedal change. “I was also incorporating percussive sounds, like the chicharra sound of the violin [a method of playing the violin string above the bridge for a cricket-like percussive effect], but I had to figure out how to make all those imitative sounds. I just basically made it all up,” she says.

Mendieta’s creativity in making the tango work on the harp resonated with many of Piazzolla’s former orchestra-mates and contemporaries, who found echoes of Piazzolla’s own rule-breaking in this new tango frontier. Mendieta has played with a number of these musicians and has spent significant amounts of time in Argentina both studying and teaching, alongside names like Pablo Ziegler, Javier Cohen, and Daniel Binelli.

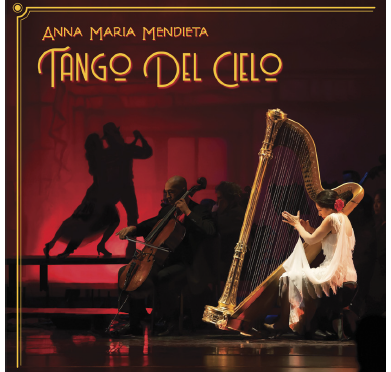

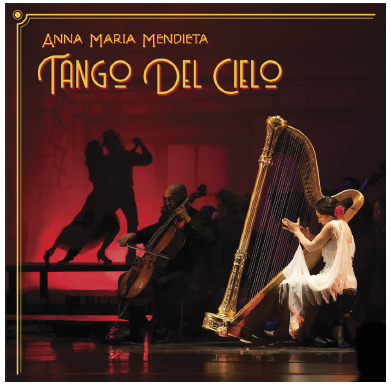

A surprising moment in Mendieta’s touring concert and show, “Tango del Cielo,” comes when the male principal dancer walks over to the harp and takes her hand, leading her to the dance floor. “Oh, the audience loves that, they really don’t expect it,” she laughs. Learning to dance the tango was, for Mendieta, crucial to understanding the deep feeling and rhythms of the music.

Even as she treads new paths in the tango field, Mendieta has not abandoned the music that made her fall in love with the harp in the first place, as the harpist for the Sacramento Philharmonic and Opera and a fixture throughout the California classical scene. Her work with the Sac Phil, along with regular performances in San Francisco and Los Angeles, has made her a rare AFM triple-carder: Local 12 (Sacramento, CA), Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA), and her original Local 6 in San Francisco, with whom she first signed on as a teenager.

Union membership has not only afforded Mendieta performance opportunities, networking, a safety net, and the knowledge that there were people who had her back, but also a wealth of opportunities to develop personally as both a performer and a business professional through the extensive continuing education programs on offer. “Local 47 in particular has that great new building and they offer so many interesting workshops—all kinds of things, from technology training to tax information, as well as every kind of music you can imagine.”

With COVID threatening the livelihoods of so many artists (and the venues in which they play), Mendieta sees the AFM as crucial in helping musicians stay connected, sharing ideas and inspiration and outside-the-box thinking, and lobbying for survival.

Personally, Mendieta spent the shutdown finishing the Tango del Cielo album that she’s had on the back burner for years. It was partially completed but never quite finished due to near-constant performances and teaching.

“I just had not found the time to finish it,” she says. “So early on, when it seemed like things might be closing for a week, maybe two, I decided to take the opportunity to go into the studio and finally finish recording my parts, and I’m so glad I did because mixing them—which I did digitally with my producer—gave me something to do in those early weeks, and I did finally get the whole thing finished and released!”

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

- Lyon & Healy harp (Salzedo Model)

- Horngacher harp

- Premier harp strings (“I like the clarity of their strings.”)

- Portastand Minstrel music stand (“It’s so lightweight, it’s solid and sturdy, plus it’s small so it doesn’t block the sightlines of the harp during performances.”)