Symphonic Composer Moonlights as a Rock Star

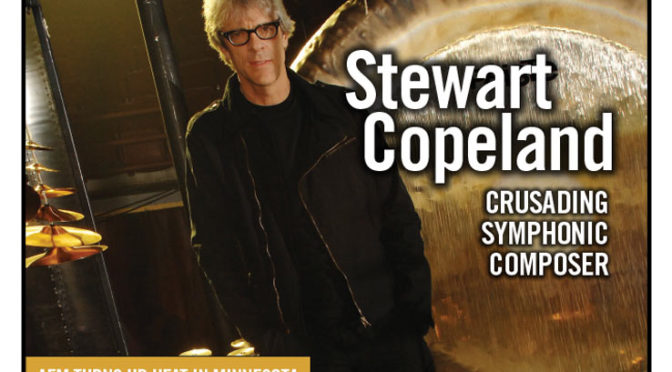

Though many rock fans still identify Stewart Copeland with the nine years he spent as founder and drummer of the Police, those in the classical music world have come to respect his composing, which has been the Local 802 (New York City) member’s focus for the past 30 years of his career.

Just before The Police stopped touring, Francis Ford Coppola approached Copeland about Coppola’s new film Rumble Fish (1983). “My blood ran cold. I was young then and didn’t have the experience I have now,” Copeland says, recalling the learning curve coming from the world of rock music.

For example, Coppola said he wanted strings. “I called up some strings, and I imagined 10 guys would show up, I’d talk to them, and we’d get a groove going. The look of bewilderment on their faces was unsettling. They didn’t listen to any of the bull coming out of my mouth. They were looking at the chart. That whole concept of adherence to the page was quite startling, and as it sank in, I began to realize it was extremely wonderful,” says Copeland.

With that realization his love for composing and respect for classically trained musicians grew. “The devotion of their whole career is to accurately reproduce what’s on the page because 20 feet away there’s somebody else with the same line. As long as all 90 individuals [in an orchestra] obey the page dutifully and faithfully it will be a beautiful piece of music. For the composer, to dispense with the chit-chat and just put it on the page, is really kind of a breakthrough,” he says.

A long-time union musician, Copeland was first a member of the British musicians’ union and then joined the AFM when he moved to the US. It was when he began composing, that he realized more benefits of AFM membership. “When I got into film composing, much more in the world of orchestral players, I appreciated the power of the union to get a better environment for musicians,” he says. “If it weren’t for the union, there are all kinds of payments that the players would not get. The negotiation power of one player does not exist because the competition for the jobs is so extreme.”

In the world of composing, one successful job often leads to others. Copeland took on numerous projects, and became well known for his scoring and soundtracks He worked on projects that varied from television series like The Equalizer (1985-1987) and Dead Like Me (2003-2004); to the video game Sypro the Dragon (2002); and films like Wall Street (1987) and Taking Care of Business (1990).

He gradually got into other types of projects that allowed him more artistic freedom. However, he says he will always be thankful for the skills he’s learned over 20 years “as a hired gun film composer” working with various film directors. “The professional film composer has the widest skill set of any musician because he has to go to places that his instincts wouldn’t take him,” says Copeland. “I learned all kinds of useful stuff that I now apply to my own artistic vision.”

Through Rumble Fish Copeland had met Michael Smuin, head of the San Francisco Ballet, who proposed that Copeland compose a ballet. “It wasn’t real successful,” concedes Copeland. During a subsequent press conference, he was asked if he planned to write another ballet to which the composer jokingly replied, “Sure, after I finish writing my opera.” The Cleveland Opera picked up on the comment and said, “How about we put it on?”

That led to his first opera composition. “At the time, I was not a big fan of opera,” says Copeland. “I didn’t really ‘get’ the first few I saw until I saw a David Hockney production of Tristan. That was an education as to what it’s all about with opera: the power, the majesty, the kick-ass of a big orchestra and a big story.”

According to Copeland, one of the attractions and challenges of writing an opera is the size of the score. “An opera is 90 minutes, so the volume of it is a challenge; but it’s so much fun and so engrossing to do. It is a very complex medium. You pick up new things [each time], which you put into the next one.”

Last spring, his fourth opera, Edgar Allan Poe’s Tell-Tale Heart, premiered in the US, following its 2011 London premier. “I also wrote another Poe opera piece Casque of Amontillado,” he says, “Poe’s language is so good that you just take it straight off the page, nudge it around a little bit, and it becomes verse.”

In 2008, Copeland was commissioned by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra to write a piece for the five-member world percussion group D’Drum to perform with the orchestra. The story of the making of that successful piece is told in the documentary, Dare to Drum: A Musical Journey with Stewart Copeland, D’Drum, and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra to be released in 2014. (See the story in the September 2013 IM.)

Copeland sees this as an example of the type of innovative project that can help orchestras build new audiences, as well as private and public support, as they struggle like all musicians in moving into the digital age. “It’s particularly harsh because the costs are so high for classical music,” he says. “The amount of training and vocational commitment it takes to be one of those musicians is so much higher. But it just is not paid for by ticket prices, so the money has to come from private sources.”

“They do seem to be trying to attract sexy new ideas into the orchestra world,” he says, adding that the efforts by orchestras to bring in pop musicians to “give it a try, driving a 90-piece orchestra” have met with limited success. “I am a crusader, educating musicians who have the depth of talent for large-scale enterprises. I encourage them. It’s really a lot of fun. It’s magnificent when you hear the orchestra pump it out. Learning to score a chart is easier than learning French. There are fewer words, and being musicians, the people I’m talking about already have that covered.”

Stewart’s current projects include a concerto for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra entitled Poltroons in Paradise “for percussion and big-ass orchestra,” which is just about finished. He is also scoring the original 1925 black and white, silent version of Ben Hur. You can hear the excitement in Copeland’s voice as he describes it: “The scale of the movie is mind boggling—thousands of extras and these unbelievable scenes. Warner Brothers lent me the movie and we just finished digitizing it.”

He’s cut the 2-hour, 40-minute film to 90 minutes, completed the score, and now he has to put it all together. The Virginia Arts Festival Orchestra will premiere the work Easter 2014. “It will be a movie, big orchestra, and me banging on the drums,” he says.

Much of the music was written for Copeland’s two-plus year presentation of Ben Hur that toured arenas around Europe, starting in 2002. “They filled the arenas with dirt and had a cast of 100s, and they did all the battle scenes and everything,” he says.

Though Copeland identifies himself as a composer these days, that doesn’t mean he’s given up on touring entirely. There was the wildly successful 2007/2008 Police reunion tour, and he spends part of every summer touring with various groups he’s put together over the years.

“I normally play in the summer and completely lie fallow for the rest of the year,” he says of his drumming. “I say, ‘Oh, shit, it’s April,’ and I dust off the drums and start playing again, and it all comes back.”

Aside from music Copeland enjoys film, and has helped make two documentaries The Rhythmatist (1985), based on his trip to Africa looking for the roots of rock and roll, and Everybody Stares (2006), created from his own Super 8 early touring footage of The Police. More recently Copeland has launched a series of YouTube videos recorded in his studio, the Sacred Grove.

But, that’s just for fun he explains: “I’ve got every inch of the studio miked up, line checked, and working. Plus, I have six cameras with six hours of memory. My buddies show up, the cameras go on, and the Sacred Grove is in record, burning to hard drive. We jam, we goof off, we tell war stories, and we jam some more. Then, we play it back and overdub on it. I’ve got every known instrument on the planet here. They take a solo … they blast away. Then, they all go home and months later I send them a movie of all that stuff carved up and pieced together.”

“While I was a film composer under a deadline those instruments would gather dust. And any time I spent hooting away on my bass clarinet just for the fun of it felt like time wasted,” he says. “Then I came to the realization that it’s not goofing off, that’s what I’m here for,” he concludes.