by Tony D’Amico, President Theatre Musicians Association and Member of Locals 9-535 (Boston, MA) and 198-457 (Providence, RI)

by Tony D’Amico, President Theatre Musicians Association and Member of Locals 9-535 (Boston, MA) and 198-457 (Providence, RI)

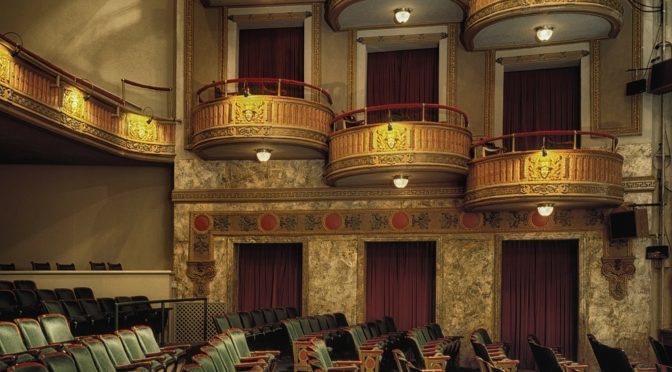

Musical theatre and technology have always had a bit of an uneasy relationship. The modern musical was born out of the light opera traditions of Gilbert and Sullivan in the 19th century, where it was the norm for large pit orchestras to accompany the singers on stage. The Golden Age of Theatre (1940s-1960s) saw the premieres of many of the classics of the art form by the likes of Porter, Berlin, Rodgers and Hart, and Gershwin, and culminating with the shows of Rodgers and Hammerstein.

As a rule, those shows used large orchestras. Oklahoma (1943) used 28 musicians in the pit and Carousel (1945) had an orchestra of 39. Not only did audiences expect a show to have an ensemble of this size, there was no viable technology that could replace musicians.

Things changed with the introduction of the synthesizer into musical theatre. The 1987 Broadway contract allowed the synthesizer into pits, and the instrument was used mainly to enhance the sound of orchestra members still numbering in the 20s. The 21st century brought us the Virtual Pit Orchestra; a device whose manufacturer claimed could emulate the entire pit orchestra, with just one person, known as the “tapper” controlling tempo and dynamics. The machines proved buggy (with entire productions coming to a standstill while the computer rebooted), and the sounds they produced were less than desirable.

New shows generally use smaller orchestras, and those players who are hired are asked to do more. This is even more the case when a Broadway show is configured to go out on the road. For example, Something Rotten, which played on Broadway for approximately a year and a half, had an orchestra of 18. When it went out on tour, the score was orchestrated down to 11 musicians. Phantom of the Opera opened on Broadway with an orchestra of 31 players. The tour out now is configured for 16.

Thanks to the admirable talents of musical theatre orchestrators, these reductions work well, but it also means players are being asked to do more. A Broadway production that had four reed players might be reorchestrated for two for the national tour. String sections are always ripe for downsizing. Going back to my previous Something Rotten example, a string quintet on Broadway has been trimmed to a duo of violin and bass for the tour, with synthesizers picking up the slack.

Of course, this is all driven by economics. Musical theatre in an expensive enterprise, and touring shows even more so. But, it’s a fact that audiences like shows with big orchestras. The 2008 Lincoln Center revival of South Pacific had a 29-piece orchestra, and both critics and audiences took notice.

This is a subject that gets discussed a great deal at Theatre Musicians Association conferences and board meetings. What can we do to convince producers that the investment in well-staffed pit orchestras will pay dividends in positive reviews, audience appreciation, and consequently ticket sales? It is clear that the public can, in fact, tell the difference when a production uses a full complement of excellent professional musicians. Ticket prices are continually climbing higher, and theatregoers should demand a first rate experience, which I would argue includes a band that uses the forces the composer intended.

One of the cornerstones of TMA’s mission is to educate the public about, and promote the idea of, quality musical theatre. Countless hours are spent at TMA conferences and in executive board meetings discussing how we can spread this idea. Informational leafleting before shows with an invitation to stop by the pit before the show or at intermission, ads in playbills, letters to the newspapers, and comments to online reviews are some ideas we are discussing to increase pit musician visibility to the audience. Please feel free to contact me at www.afm-tma.org if you have suggestions.