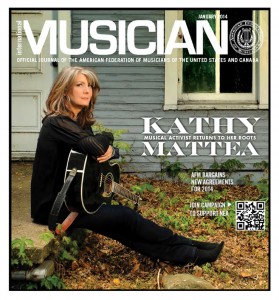

Kathy Mattea of Local 257 is considered one of the all-time most successful female country musicians. In her more than three-decade career she has had around 30 top 40 country hits, won a couple Grammys, and she’s twice been named Female Vocalist of the Year by the Country Music Association.

Born and raised in West Virginia, Mattea has lived in Nashville since the very beginning of her music career. About seven years ago, she went back to her roots musically. Her exploration of old-time Appalachian music, which has led to two albums, came about accidentally, born of tragedy.

“There had been a big mine disaster in West Virginia. There were 13 miners trapped for four days at a mine near Sago. I was riveted by this story and frankly shocked at how much emotion I felt for people I had never met,” she says.

The drama ended sadly when the bodies of 12 miners were finally recovered; only one man survived. When Mattea was asked to sing for a television broadcast of the public funeral, one of her friends commented: “This is what music is for, helping us process grief that we don’t even always understand.”

“Maybe that’s what I’ll do with all this emotion,” Mattea recalls thinking. “I’ll make a record about coal mining and get it out of my system. I thought it would be a little side project, but it was a much bigger experience than I expected.” For one thing, having left West Virginia at 19, Mattea discovered a connection to her own roots through coal mining songs that she didn’t expect.

“I kind of thought maybe I didn’t have the authority to sing these songs, but I felt drawn to do it. It was like going back and picking up a piece in your jigsaw puzzle that was missing and you didn’t even know it was missing,” she explains. “My grandfathers were both coalminers; I thought coal mining was their story. I came to understand that I was heavily influenced by coal, even though nobody was coming home covered by coal dust in my house. So many of the little vignettes I grew up hearing got tied together into a larger narrative, and I began to see where I came from in a completely different way.”

Yet, it wasn’t easy. The simple songs challenged everything Mattea had been taught as a professional singer. For example, she says the song “Black Lung,” written by Appalachian music icon Hazel Dickens, took her months to master and changed the way she thought about singing. “There is a wonderful combination of anger and dignity in that song that is sort of the crux of what these people have lived with for generations.”

“I’m a trained singer; I’ve practiced for years. Contrast that with Hazel Dickens who wrote that song about her brother and doesn’t have an ounce of training. It’s a seamless connection from the emotion to what comes out of her mouth. I’ve been moved to tears by her version of the song. I had to not perform that song,” she continues, explaining how she struggled to find a visceral connection. “That taught me how much I don’t know about singing.”

“That was the gift really of all this music,” she says. “All of the songs were very simple, but for me, it was almost like there was a little wall deep down in me that I had to push down and open up a level of vulnerability. It’s really about honoring the stories. I had to strip away a layer of my own ego to do it.”

From the outside Mattea’s new focus on old-time tunes, and away from pop country, might look like a major shift, but she doesn’t feel that way. She explains that it’s just a continuation of the way she’s looked at music from the beginning of her career: “It looks like a big left turn, but it really felt more like each product is continually unfolding.”

“I was very lucky because I had a producer early on who is a very wise man,” she says. “He kept saying to me, ‘It’s the song. Don’t let them tell you any different; it’s not the bells and whistles; it’s just the song.’ I was taught to let the songs lead me.”

And the album Coal, released in 2008, wasn’t enough. “I felt like I had discovered this treasure trove of songs,” she says. “I had found this amazing world that I had never really explored, so I didn’t want to stop.”

Calling Me Home (2012) has more songs about coal, but also songs about Appalachia and the special attachment to place that people from the area feel. “Even for me now, at 54, I feel like an expatriate Appalachian, who happens to live in Tennessee. It’s a big part of my identity,” Mattea explains.

Just as Appalachia is part of Mattea’s very being, so is standing up for what she believes in. That’s one of the reasons she’s a strong supporter of the union. “Unions help people, who may be in the position of having no power, to discover a power bigger than each individual. When people stand together anywhere in the name of what they have in common, and in the name of dignity, there’s a principle that starts to work through them and that is the beauty of unions.”

Her mother’s father, a United Mine Workers organizer, told stories of him and his friends hiking 50 miles just to hear labor organizer Mother Jones speak, and hopping trains for clandestine organizing meetings. And when her mother’s husband died suddenly, the union office gave her mom a job. “Every Christmas, for the rest of her life, she wrote a check to the UMW,” says Mattea of her mother.

And when it was time, Mattea was proud to join the union. “I remember thinking: I’m a real musician, now,” she recalls, when joining the AFM 28 years ago.

In recent years, more than ever, Mattea has become a spokesperson for causes she believes in. She gives talks, accompanied by music, that focus on environmental issues, in particular mountaintop removal—where the mountaintop is literally blown off to get to the coal underneath.

Another cause close to her heart is the role of the arts in our daily lives, especially how it affects young people. “I love talking about that. My dream is to go before Congress and talk about why the arts are important, and not just because of math scores and statistical stuff,” she says. “You can’t measure the soul searching the arts give us.”

“Music can help us communicate with each other. I can make an argument for 30 minutes that won’t convince you, but I can sing you a song in three minutes that will change your heart,” she contends. “A great example is ‘Hello My Name Is Coal’ on my latest album. It’s a song that really honors both sides of the coal issue, without condemning anyone. The arts knock on the brain from the back door. It makes us feel something first and then teaches us something. That’s a vehicle for change.”

Mattea will take to the road again this month offering a show that combines these newer Appalachian songs with some of the tunes that made her famous. “I mix it up; I’ve rearranged some of the old songs so they have new life. That was one of my challenges because the tone of the coal songs was so much darker. It’s great to sing about the whole range of human experience.”

At concerts she strives for intimacy with the audience, telling stories and sharing songs, even taking requests. “If I do my job right it’s like going on a journey and each song opens up another nuance of the journey, and the momentum keeps pulling you forward,” says Mattea.

Sometimes referring to herself as a “recovering country music star,” Mattea reflects on how her show has changed. “I had a couple buses, and the semi, and a big crew, and a band, and all that, and it was great fun. What I really wanted from the very beginning was just to stay connected to music in a way that felt real, exciting, and interesting; and that’s kind of what happened.”

“For me, it’s about a connection with the audience, and with the songs, and where we are going next,” she says. “I kind of feel lucky. I came along at a time when there was still some innocence about it. I watch young people coming up now—everything is programmed; spontaneity has been taken out of it.”

To them she offers: “Someone said to me early on that you have to stay in touch with the love of doing it. It can’t be about fame and money and all that. If you stay in touch with the joy and fulfillment, time and the world fall away, and there’s nothing but the music. That will lead you where you need to go, and the rest will take care of itself. If you get rich and famous, and you hate the music, then you haven’t done anything. That’s a special kind of misery.”

As far as her own career goes, Mattea has let things progress organically, letting the songs lead her to a place where she is tackling music that would have been challenging earlier in her career. “I had to have some life experience,” she says, adding that her voice itself is now better suited to the old-time Appalachian music. “I listen to my young voice now, and it sounds so innocent. I don’t think I could have sung these songs with that voice. I have more resonance than what I had when I was younger. In the middle of your life, there’s a richness that comes into the low end of your voice.”