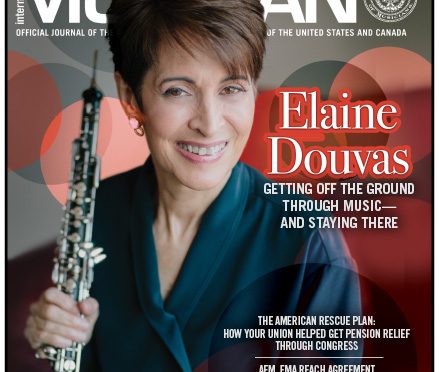

Getting Off the Ground Through Music—And Staying There

Elaine Douvas fell in love with classical music as a first grader in ballet class. The “Sleeping Beauty Waltz” by Tchaikovsky made her spirit soar, and by age seven she knew she wanted to be a professional musician. She started on piano, changed to violin, and in sixth grade decided to switch to a band instrument so she could play in the school band with her friends. She endured a summer of French horn, which did not suit her, and ultimately found the oboe. “I think I chose the oboe because it was rare and I thought I’d have more opportunities—and that kind of turned out to be true,” she says. “I am so lucky I found the instrument that works for me.”

To say the oboe worked for her is an understatement. Douvas, a member of Local 802 (New York City), is an institution in the oboe world, having served as Principal Oboe of the Metropolitan Opera since 1977 and oboe instructor at The Juilliard School since 1982. She teaches in multiple schools, conservatories, seminars, and festivals across the globe and is considered one of the most influential music teachers in the US. This teaching, and the importance of education and the influence of educators on young musicians, has always been imperative to Douvas.

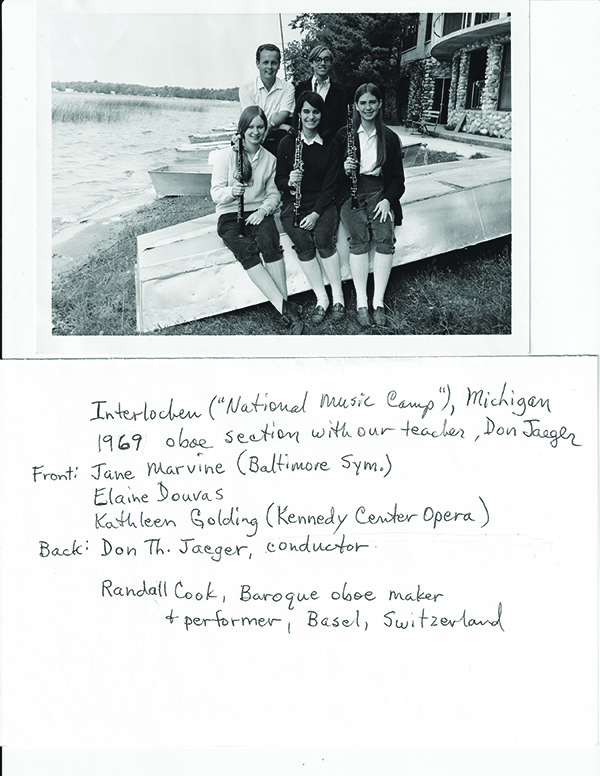

The “turning point” in her life was attending three years of high school at Interlochen Arts Academy. “I was only in college (at the Cleveland Institute of Music) for three years after Interlochen, and I was still heavily drawing on that high school repertoire and experience to start my first job in the Atlanta Symphony when I was 21,” she says. “I was inspired by the example set by my teachers who put so much energy and devotion into their work—it was astonishing. It truly is a sacred trust, and I hope I have inspired many students to carry on after me too. We really want the next generation to surpass us and take the standard higher than we ever imagined.”

To that end, Douvas has been full of ideas—and taking action—on making the best of the pandemic as an educator. Like so many of her colleagues in the classical music world, Douvas has been getting through the pandemic by teaching online. “I devote so much of my time to try to be sure the students aren’t becoming discouraged, that they can get through this stretch and keep pursuing their dreams,” she says. “I spend a lot of time brainstorming projects that they can do to have goals, but also to make money.”

For example, she has given several of her recent graduates ideas such as starting a “Warm-up Support Group” for those who find it hard to make themselves play every day (and charging a modest subscription fee); other students have connected by starting a Listening Study Group on a “piece of the week”: a show and tell of recorded interpretations each student has discovered and plays for the class. Several of her students have started reed-making intensives for online instruction using close-up cameras and sound tests on the reed alone.

Currently, Douvas is working to start a summer festival for woodwinds as part of the Hidden Valley Music Seminars in California and raising funds so that the festival can be free for participants.

While Douvas loves teaching, she considers her work in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra to be her true profession. The current state of the Metropolitan Opera and recent events occurring from decisions made by the Opera Board have been difficult for her and all her colleagues to endure, she says. Met musicians were furloughed early last year and have not been paid since April 1, 2020—one of very few full-time orchestras in North America receiving no pay at all during the pandemic. On top of that, Met officials have been in a labor dispute with backstage workers, and on New Year’s Eve 2021 the Met hired non-Met (and therefore non-union) musicians to play its virtual NYE Gala. “These things are all very painful,” Douvas said. “I’m really proud to be part of such a great orchestra … and the players are going to hold tenaciously to all the conditions that are needed to preserve artistic integrity and our stature as a world-class ensemble.”

Douvas has been an AFM member since 1972—for 49 years—and is not only a proud member, but also discusses the benefits of the union to young musicians in a career development class she teaches at Juilliard. “Because of the union, so many orchestras have been able to negotiate a living wage and longer season, and we would be nowhere in this profession if it weren’t for the opportunity to band together and bargain as a unit,” she says. “I’m happy to contribute my union dues on whatever work I do so that the union can provide services to musicians who need it. Nowadays, I’m one of them. I’m so glad we have skillful union representatives to help us in our negotiations and our legal matters.”

Despite the pandemic and the current labor issues confronting the Met Opera, Douvas is eager to get back to playing. One of the four woodwinds in an orchestra, the oboe often is used by composers to express emotional moments in a piece. “Woodwinds all have very soloistic parts; they are heard individually,” she says. “I don’t think it’s going too far to say they are sort of the crown jewels of an orchestra; they are the ones that are heard the most.” Douvas says the oboe is an instrument perfectly suited for her because of her preference for playing long, expressive lines—rather than the more acrobatic parts for other wind instruments like flute and clarinet.

She likens her playing to another personal passion: figure skating. Douvas skated for a while as a child but gave it up in order to focus her time on practicing her musical instruments. She always regretted quitting, she says, and during the Metropolitan Opera strike of 1980, when she suddenly had a lot of free time on her hands, she took it back up. “I skated fanatically for [the next] two years,” she says, practicing four to five days a week, getting up at 5:30 a.m. to practice before going to rehearsal at the Met each day. “It was kind of crazy, but I was trying to bring back the days when music was so fun, and I tried to pretend skating was my work.” She realized she could not keep up that pace, so she pulled it back and has been skating more recreationally ever since.

The juxtaposition of skating and music, however, has been with her ever since. “A lot of my imagery in interpreting music comes from the wish to be a skater or a ballerina,” she says. “Playing the oboe, you can still get off the ground; you can still create sweep and line, and things that are high and things that are low. I see in my mind’s eye skating choreography, or ballet choreography, in a lot of the things that I work on. And there’s just nothing more important to me than getting off the ground and staying off the ground.”

The same goes for when she is a listener at a concert, and she hears music that is so uplifting that it creates a magical, almost out-of-body experience. “If I can manage to do that now and then, that’s what I’m trying for: to transport people, to feel weightless and uplifted.”