Michael J. Miles, of Local 1000 (nongeographic), banjo player and writer, performed his highly acclaimed one-man show “From Senegal to Seeger” in January in Beacon, NY, to benefit the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc., an environmental nonprofit founded in 1966 by the late folk singer Pete Seeger.

Through education, green initiatives, and the annual Great Hudson River Revival music and environmental festival, the organization campaigns for the protection of the Hudson River and surrounding wetlands and waterways. Its iconic schooner Clearwater, a replica of an 18th-century ship that Seeger commissioned in 1969, has come to symbolize its mission. Last year, 2019, marked the 50th anniversary of its maiden voyage during the summer of Woodstock.

The Chicago-based Miles says it was high time his city returned the favor to Seeger—a member of Local 802 (New York City) and Local 1000 until his death in 2014—who had performed several benefit concerts for the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago, where Miles was program director from 1984-1999. “Pete’s encouragement was powerful,” Miles says. “His efforts truly helped the Old Town School through some difficult times.”

Seeger was a mentor to a generation, including Bruce Springsteen of Local 399 (Asbury Park, NJ) and Local 47 (Los Angeles, CA) and Bob Dylan of Local 802 (New York City). Miles says was shocked when out of the blue Seeger wrote him to say, “Looks like you’re doing good things. Keep up the good work. … Thanks for keeping me on your mailing list.” It began a 25-year friendship, and, like many musicians before him, Miles was encouraged by Seeger, who was an early supporter of his banjo music.

Seeger was also instrumental in helping to define the Old Town School’s overall mission of espousing folk music as the traditional music of the world. “Under our roof, the Flamenco dance could be right alongside blues harmonica, which could be right alongside African djembe,” Miles says. “These were music forms and traditions that reflected the identity and the culture of the people.”

The American folk renaissance began when Pete Seeger met Woody Guthrie in 1940, so the story goes. In his one-man show, Miles weaves history and storytelling into a dazzling array of banjo, creating a sweeping social and political portrait of a classic American musical expression. With seven banjos on hand, he plays music that spans 300 years, charting the banjo from its West African roots—namely, the Senegalese akonting—to fiddle music and American protest songs.

Walt Whitman, Carl Sandburg, and Mark Twain factor mightily into Miles’s performance, but it’s Seeger’s powerful testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee that stands out. During the hearings, Seeger refused to invoke the fifth amendment. He would not be silenced, Miles says. “Pete said, ‘How is it that you think you’re more American than I am?’ He was found guilty of 10 counts of contempt to Congress and sentenced to a year in prison for each one. But over the course of appeals, it was ultimately thrown out.”

As a leader of the American folk revival, Seeger channeled America’s conscience. The iconic singer spent his life championing labor, social justice, civil rights, the environment, and peace. It was Seeger who adapted “We Shall Overcome” and helped Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders incorporate song into their activism.

To this day, Seeger’s profound impact on unions and the labor movement is unmatched. He joined forces with Woody Guthrie to form The Almanac Singers, and recorded the album Talkin’ Union. Other songs like “Solidarity Forever” and “We Shall Not Be Moved” are used by progressive activists today. Drawing on their grit and ideas, Seeger distilled Sandburg and Whitman’s narrative into songs like “If I Had a Hammer” and “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” “Pete was a fine banjo player, but it was more of a tool for him to tell his story, to fight for the causes that he believed in,” Miles says.

Miles joined the AFM in 1977, just out of the University of Illinois, Urbana, and has played guitar and banjo professionally ever since. During a difficult time when his wife was gravely ill, he needed a more generous health care plan. He started looking around and found it in his union. It’s part of the power of a collective, Miles explains. “I can also honestly say that without the health insurance that I have had because of my union membership, my family would have been bankrupted by medical expenses. So I’m a very grateful member,” he says.

The story of the union cannot be told without Pete Seeger. The story of the banjo cannot be told without Seeger. At his recent show, over the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend, with Seeger’s daughter Tinya Seeger and other close friends in attendance, Miles received a standing ovation. “[Seeger] believed a collective voice has the power to change things for the better,” Miles says. “Pete witnessed and made it happen with songs that provided solidarity.”

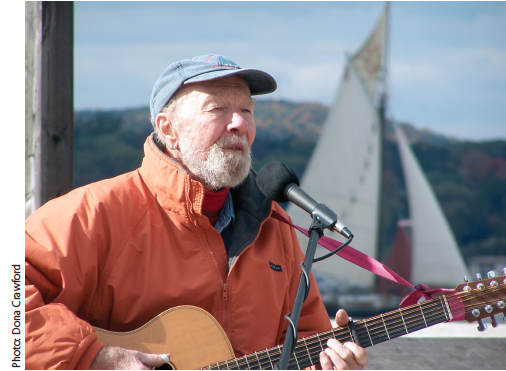

Pete Seeger and the sloop he had built, Clearwater. Clearwater is recognized as America’s Environmental Flagship and is among the first vessels in the United States to conduct science-based environmental education aboard a sailing ship. Photo: Dona Crawford

Michael J. Miles, banjo player and writer, recently performed his one-man show “From Senegal to Seeger” in Beacon, NY, to benefit the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc., an environmental nonprofit founded in 1966 by the late folk singer Pete Seeger. Photo: Louis Alvarez