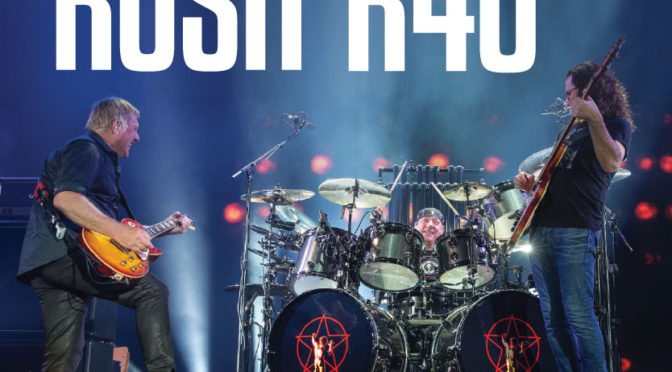

As Rush rounded out its three-month, 34-city R40 tour last year it felt like, and was, the end of an era. Band members Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, and Neil Peart weren’t shy about admitting that this was most likely the last large-scale tour for the Canadian trio, if not their last tour altogether. The whole show was designed with that in mind.

Rush was founded in the summer of 1968 in a suburb of Toronto. The R40 tour celebrated 40 years of the three friends performing together. Peart had replaced the original drummer in 1974, just before their first US tour.

All three musicians have been union members throughout their careers. Forty-seven-year Local 298 (Niagara Region, ON) member Peart, joined the AFM in 1968. Lifeson and Lee joined Local 149 (Toronto, ON) in May 1970.

“That was a big day for us; we considered ourselves professional musicians,” recalls Lee of the day he joined with Lifeson. “We were part of something bigger than us. I’m a believer in unions and helping our fellow musicians.”

Throughout the years, most of the band’s tours focused on new material, with a few older fan favorites sprinkled in. But, the idea for R40 was to present every era of Rush’s discography in reverse chronological order, giving “equal weight” to each period of the band’s history. They wanted to include the most popular tunes—both the biggest hits and the obscure ones that diehard fans have long-requested. Lead singer Lee, known for his vocal range, especially early in his career, initially had doubts he could still sing some of the older tunes.

“I thought that was the case with most of the songs that we picked for the tour, but somehow or another I was able to regain that range for this tour,” he says. “I was deathly afraid of doing songs like ‘Lakeside Park’ and ‘Anthem’ [both from 1975], but I was able to shape shift into a younger version of myself and make that happen. I don’t think I’m afraid of anything else anymore!”

You Can Go Back

Then, the challenge for the band became recalling the emotional energy that the songs brought forward sometimes 30-plus years ago. “That was a long time ago. The songs feel a bit naïve and dated, and there is something that sort of makes you stop before you do it … Can I really sing that and mean it?” he says. “But, on this tour, there was such an exuberant spirit on stage and in the audience that it became a celebration of the past and I think that helped me get my head in the right frame of mind.”

Then, the challenge for the band became recalling the emotional energy that the songs brought forward sometimes 30-plus years ago. “That was a long time ago. The songs feel a bit naïve and dated, and there is something that sort of makes you stop before you do it … Can I really sing that and mean it?” he says. “But, on this tour, there was such an exuberant spirit on stage and in the audience that it became a celebration of the past and I think that helped me get my head in the right frame of mind.”

In the end, Rush pulled-off energized versions of older tunes that feature the mature band’s expertise and skill. On the R40 Live CD and DVD, recorded and filmed at two sold-out shows in the band’s hometown of Toronto, you’ll find songs that the group hadn’t performed live in many years, and in the case of “Losing It,” had never performed live.

As planned, the band revisited all past eras of Rush in its retrospective, from Clockwork Angels (2012) to the guitar-driven ’90s sound, heavily synthesized songs from the ’80s, the progressive rock era, ending with just three men jamming out on their instruments.

Through all its years of evolution, Rush remained an enigma, consistently creating a sound that the three musicians agreed was right for the times. Defined by the imaginative spirit of Peart’s lyric writing, arrangements from Lee and Lifeson, and the talent of three expert instrumentalists, the trio has inspired a passionate following.

“Generally, we’ve always agreed on what kind of music we want to write and what kind of music we want to perform; any differences really come down to how we want to go about recording and what priorities certain instruments should take,” says Lee, admitting they didn’t always agree, for example, on the role of the keyboards.

The Writing Process

As the lead singer, Lee says he works most closely with Peart to “flesh out which lyrics work best and which lyrics I can write the most successful melodies for, and how that’s going to meld into the bits and pieces of music that Alex and I come up with.”

“Because so much of the final song is dependent on how the vocal melody is written and woven into the song, it sort of makes sense that the major part of the construction of the song and the arrangement falls into my lap,” explains Lee. “Of course, I balance everything and discuss everything with Alex and Neil. I sort of act as a sound board or editor to Neil in terms of what lyrics he’s written that I can use.”

However, Lee says Rush songs don’t always begin with Peart’s lyrics. “Sometimes we write a completed song, we play it for Neil, and he will see if he can write something for that. Other times it kind of goes hand in hand: I’ll have the lyrics in front of me for a few different songs that have yet to be written, and as Alex and I are putting a song together, we gravitate towards the mood of a particular lyric that seems to suit the song. Neil will then sort of go back and rearrange what he’s written to suit the music.”

And even though the process has been expertly honed through 40 years of combining their creative energies and intuitions, much of songwriting Lee admits still boils down to trial and error. “Once human beings start playing it, it takes on a life of its own,” he says.

Throughout their career it was never about staying a course, but about topping their previous work. “We just try to do something as good or different. It’s all about a body of work. And so there has to be something about it that feels fresh; we have to feel like we’re breaking new ground,” he says.

Known for their long tunes, record companies initially pressured Rush to create songs that were more along the lines of a neat, three-minute format. “There is no record executive in the world that doesn’t want to put some pressure on you to write some sort of hit single for them. That’s understandable; that’s their business. In our early days there was much more pressure to conform and be more traditional, and as we became successful doing our own weird thing, they sort of left us alone,” says Lee.

“We’ve always had battles with labels over the length of our songs,” he continues. “They’ve always wanted to edit our songs into shorter versions. I have no objection with the record company requesting a shorter version of the song for the radio, as long as, on the flip side of that, the full version exists. That’s our caveat.”

Lee says the record company relationship has changed when it comes to new bands. “The means of exposure are so different from in the early ’70s. There is less patience and willingness to invest in young talent. That was an advantage we had—record companies were looking for bands and willing to sign you to multi-year deals to allow you to turn into something. Now they want you to be happening already,” he says.

Just the Three of Them

Unlike other bands that grew in terms of size along with their popularity, Rush has always remained three guys—close friends to this day—who are dedicated to being the best band they can be. They meticulously orchestrate MIDI controllers in live performances to make their stage show match the sound of recordings.

Lee explains why the band made and stuck with the decision to be just the three of them, “We didn’t want to mess with the delicate balance of our interpersonal chemistry. It’s very difficult to be a rock band; we find that three is a really good number for longevity—there are no factions in three.”

Lee explains why the band made and stuck with the decision to be just the three of them, “We didn’t want to mess with the delicate balance of our interpersonal chemistry. It’s very difficult to be a rock band; we find that three is a really good number for longevity—there are no factions in three.”

“The other reason was that we felt our fan base would rather see us wrestle with technology, than have another person appearing on stage with us,” he says. “They see us as a three-piece band and we didn’t want to mess with that vision.”

The result has been a tight and supportive trio that has helped each other in good times and bad, like during its five-year hiatus following the death of Peart’s daughter and wife. When Peart told his bandmates to consider him retired after Test for Echo in 1996, they didn’t know if there would be more Rush.

Lee recalls the band’s decision to come back in 2001. “Of course that whole decision was fraught with worry of every kind; we didn’t know whether the magic we had before working together would return, or whether Neil would have enough heart and soul to be a functioning member of the band after what he had been through,” says Lee.

It took them 14 months to write and record Vapor Trails, and following its release they began their first tour in six years.

Challenges of Touring

Though the band put on shows this summer that were every bit as energized and precise as any time in their careers, this is most likely the finale for their touring days. Both Peart and Lifeson have health issues that make the lifestyle difficult, if not painful. Though he is able to play through the pain with the energy and accuracy of his younger years, Lifeson’s arthritis has made touring more grueling than before.

Peart, known for being a very physical drummer, suffers from tendinitis. He also relishes his family life and spending time parenting his six-year-old daughter. In a recent article he wrote for Drumhead magazine, Peart says, “The reality is that my style of drumming is largely an athletic undertaking, and it does not pain me to realize that, like all athletes, there comes a time to … take yourself out of the game. I would much rather set it aside than face the predicament described in our song ‘Losing It.’”

Still, the band hasn’t officially retired for good. They remain open to the possibility of recording new music or having an occasional show. It’s clear that an eager and loyal audience will be waiting and ready in case that happens.